ZERO: A Dignified Contemplation of Mortality

Morris is a student and cinephile from Singapore. He watches…

Kazuhiro Soda may not be a household name in his native Japan, but the prolific director’s films explore remarkably universal themes and ideas even as they contend with culturally specific subjects. With eleven features to his name, Soda has abided by a personal series of “Ten Commandments” that emphasise the observational role of the camera more than anything else.

In the documentary’s true spirit of improvisation and letting reality speak for itself, these commandments shun the use of scripted production, superimposed (or non-diegetic) input, short takes, and thematic dogmatism, among others. Mental, released in 2008, is arguably one of his more recognised films, chronicling the lives of mentally ill patients from the Chorale Okayama Clinic, a community mental health facility. While these patients come from varying backgrounds and suffer from varying illnesses, they all see the same doctor – an unassuming but affable elderly man named Masatomo Yamamoto.

Twelve years have passed since and Dr. Yamamoto is considerably frailer, approaching the sunset of his career and planning for retirement at the age of eighty-two. He still sees patients regularly, but these are presumably his last few sessions with them and intended to smoothen the transition to another healthcare specialist which they must undergo. Some of his patients in Mental have either passed away or moved on; others remain, significantly older and not unfamiliar to the viewer. Many have been struggling with depression for much of their lives, and they must now come to terms with Dr. Yamamoto’s imminent farewell.

Zero, Soda’s latest documentary feature and a follow-up to Mental (the former’s Japanese title reads Seishin [Mental] 0), examines these interactions between the aging doctor and his clients with rare and touching empathy. True to its subtitle as an “observational film”, it rarely imposes upon its subjects any overarching narratives or talking points and accords them the dignity of living their day-to-day lives on camera. And like many of Soda’s other works, it never feels rushed; our camera follows Dr. Yamamoto from place to place, soaking up the voices and gestures of his various encounters.

Return to Zero

Beginning in medias res in the Chorale’s consultation room, Zero finds Dr. Yamamoto with one of his patients who was also present in Mental (whose footage, black-and-white for contrast, bookends some of the present-day scenes as flashbacks). The patient informs him that he records all of their conversations, the better to hear the doctor’s words and advice every day. He struggles to find satisfaction in his life, has often had to quell many ordinary desires – such as a new CD or manga edition – due to lack of money or other reasons. It is not an uncommon malady, especially in fast-paced and metropolitan Japan whose consumer fads are in rapid, constant flux.

Dr. Yamamoto, instead of prescribing medication of any sort, adopts a comparatively zen approach to his patient’s predicament: he offers a suggestion to “place [oneself] at zero”, to stop and relinquish all desire for the time being, in order to fully appreciate life itself and the blessings that come with it. “Maybe once a week”, he muses, it would be beneficial to sit back and take stock of whatever is already at hand, to be “thankful to be alive” and content that there are things worth desiring. “You can’t do that every day.”

This concept of cherishing both what one desires and desire itself undergirds much of Zero and its portrait of Dr. Yamamoto. A persistent workaholic for most of his life, he has, since his schooling years, dedicated himself to treating and serving the “weak” and “unwanted” members of polite society, shunned and stigmatised for their mental condition. And while his patients continue to need treatment, Dr. Yamamoto has his own mortality to contend with, his own health to consider apart from the community-based clinic whose nonjudgmental acceptance of those in need of psychiatric help has been a lifelong inspiration to many.

Even twelve years prior, the hair on Dr. Yamamoto’s head showed signs of greying, and his face was already adorned with a pensioner’s wrinkles. In Zero, with his hair fully greyed, his gait more pronounced, and his shoulder dislocated not too far back, the doctor gives a farewell speech to his fellow practitioners. What most patients are lacking, in his opinion, is simple respect; little of it is being accorded to them by the state’s intrusive and rigidly diagnostic healthcare system. Just like how his friends recommend going out and enjoying himself despite him having a dislocated shoulder, he quips that patients often feel the same helplessness when receiving generic advice of this kind.

A Hidden Life

The second half of Zero acquires an even more intimate dimension, as Soda trains his camera away from the multitude of patients at Chorale and onto Dr. Yamamoto’s personal life. Yoshiko, his dementia-ridden wife, was once his domestic pillar of support and allowed the doctor to focus all his energy on treating new patients; having lost much of her mental clarity, it is now Dr. Yamamoto who serves as her sole caregiver. He brews tea for them, orders sushi for dinner (which Soda himself is invited to partake in), and reminisces about the decades of their marriage through which the love and affection between them have endured strong.

They visit an old friend one day, who shares excitedly about her relationship with Yoshiko – about their shared love for classical music, kabuki (a Japanese theatre form), and even betting on the stock market. Through her conversations, another side of Yoshiko emerges, that of the housewife who made numerous sacrifices for the sake of Dr. Yamamoto. When some of his patients insisted on staying with him overnight, she had to make room for them in the house and attend to their needs, sometimes over those of their children (grown-up and conspicuously absent from the film). The adage that “behind every successful man is a woman” holds up quite well in their case, and the doctor is quick to acknowledge it.

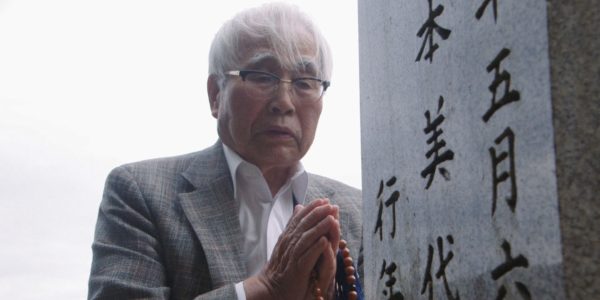

The final sequence of Zero features the couple, hand in hand, visiting the graves of Dr. Yamamoto’s parents and grandparents. As Yoshiko stumbles not infrequently, he extends his arms to support her through the slopes and rocky grounds. Reaching their destination, he moves to clean their tombstones and provide food offerings. And as they depart, their hands continue to be locked together, steady and firm.

Soda’s empathetic and compassionate filming offers a pleasantly intimate but never intrusive portrait of Dr. Yamamoto and his beloved wife; alluding to nothing, in particular, it nevertheless serves as a summation of the doctor’s long-standing career and respected legacy, along with the director’s own. Segueing away from mental illness alone into the lives of those around it, Zero is a timely reminder of life’s mortality and simplicity, and the dignity of those who live kindly and honestly.

Have you seen Zero? What are your thoughts on the documentary’s subject matter? Let us know in the comments below!

Watch Zero

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Morris is a student and cinephile from Singapore. He watches just about anything under the sun, with the exception of mediocre feel-good comedies. His favourite film is "The Room" (2003), an excellent feel-good comedy.