Words vs. Moving Pictures, Vol. 2: ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST

David is a film aficionado from Colchester, Connecticut. He enjoys…

It’s been quite some time since my last volume of Words vs. Moving Pictures, in which I discussed Harper Lee‘s To Kill A Mockingbird and compared it to the 1962 film. Since then, it has taken me a long time to try to find another book and subsequent movie adaptation that would be worthy of discussion.

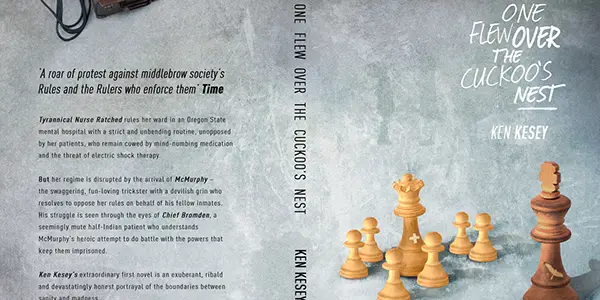

I finally settled on Ken Kesey‘s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a book and film that I felt would be fairly familiar to the general audience. Though I had read and seen both adaptations in the past, I decided to do both again back-to-back before writing. And the end results were not quite what I expected.

The Novel

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a novel that has captivated people since it was first published in 1962, and has since become a staple in some high school classrooms. The psychiatric institution represented in the story serves as a central hub for social commentary at the time, in addition to a direct critique of mental hospitals in general, which had not yet undergone deinstitutionalization.

It was born out of Ken Kesey‘s experience working at a mental facility when he was younger, in which he worked as an orderly and interacted directly with many of the patients. It is likely also influenced by Kesey‘s experimentation with LSD at the time. The resulting novel is a surreal, intensely readable, and inspired work of art.

The novel is told from the perspective of Chief Bromden, a towering Native American chief who, along with many others, is housed in a mental institution. The patients in the hospital are split between the “Acutes,” who suffer from delusions and other mental deficiencies, yet are mostly able to talk and interact coherently; and the “Chronics,” the catatonic, wheelchair-bound patients that likely would never be able to assimilate back to regular society. The hospital itself is led by Nurse Ratched, a subtly powerful middle-aged woman who runs the hospital much like a well-oiled machine.

In steps Randall Patrick McMurphy, a rambunctious whirlwind of a man, whose overall loud demeanor and outspokenness serves as a catalyst to the hospital’s once-perfect balance. As a man who doesn’t like to follow the rules, he often clashes with Nurse Ratched, who won’t tolerate his disobedient behavior. The power struggle between the two forms the backbone of the major conflicts in the story.

The Film

The film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is directed by Miloš Forman, the book adapted by Bo Goldman and Laurence Hauben, and premiered in 1975. It stars Jack Nicholson in one of his most iconic roles, in addition to Louise Fletcher, Christopher Lloyd, Danny DeVito, and the first role by Brad Dourif. The film is noteworthy for having won the Big Five Academy Awards that year – Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Actor for Nicholson, and Best Actress for Fletcher.

The same basic outline of the story from the novel is here: Randall P. McMurphy (Nicholson) is a disruption in the previously balanced mental hospital run by Nurse Ratched (Fletcher). The patients include the Acutes and the Chronics, though many of the characters, including Chief Bromden, play far smaller roles.

Chronologically, the story differs as well, with some events, such as a fishing trip, happening much earlier than they did in the novel, and with some entire sequences playing out differently. Thematically, the novel is also much denser, and though it would be nearly impossible to include all of this in the movie, there are still some essential elements missing. When you directly compare the two, it is easily the novel that will come out on top.

Perspective

The real distinctive element of the novel is the way it is presented through Chief Bromden’s eyes. After dealing with the prejudices and inherent inequality that were part of being a Native American, Bromden became depressed at a young age and started to suffer from delusions.

The way that he views the world was now through symbolic oppression; for example, he sees Nurse Ratched and her aides running their hospital literally as a machine, with gears, knobs, and wires, and with all the patients simply being worked through as cogs. He also sees people as a representation of their power, so, though he is likely almost seven feet tall, he thinks of himself as puny compared to others due to his relative weakness (he even pretends to be deaf and dumb so as to appear less vulnerable).

As the novel progresses and McMurphy’s influence spreads, the Chief’s own delusional outlook seems to subside, and even the fog that he often saw clouding the hospital ward has dissipated. There are many important turning points for him, among them including agreeing to change hospital policy in order to watch the World Series, attending a boat trip, a fistfight resulting in shock therapy, and culminating in a huge, though ultimately tragic party for one of the other patients.

The film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is instead told from an omniscient perspective, though it is almost exclusively focused on McMurphy. Chief Bromden, played by Will Sampson, is more of a sideline player in the story, and we rarely, if ever, see things from his point of view. There are even entire scenes, such as the fishing trip, where Bromden isn’t present. Though the two stories end the same, with Bromden breaking out of the hospital and running away, because we hadn’t seen as much of his character it’s not nearly as triumphant.

Such a disparity seemed to detract from the very unique outlook that is given in the novel through Bromden’s eyes. Since he suffers from delusions, we would often get these outlandish, elaborately constructed details of what he imagines occurring around him, which, when examined, directly reflect on the power struggles in the story.

An example is when he feels the floor of the hospital being lowered late at night, and workers silently stringing up an old man and murdering him while he sleeps. When the Chief wakes up, one of the older Chronics had died. Entire sequences like this do sometimes drag on uncomfortably long in the book, but they are so intricately written that their absence is noticeable in the film. It must just have been incredibly difficult to depict something like this on-screen, and therefore a more omniscient perspective was chosen.

Characters

The characters of Kesey’s novel are dynamic creations, each embedded with a distinct personality. Other than Chief Bromden, whom I already discussed, the most important characters of the story are McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, Nurse Ratched, played by Louise Fletcher, and Billy Bibbit, played by Brad Dourif.

The character of McMurphy was a fiery presence in the novel of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. His very appearance, with bright orange hair and sideburns, serves as a disruption to the norm. When he first steps onto the hospital ward, it is almost immediately apparent that he will be a driving force. He greets every patient loudly, commanding the attention of the room, refuses to listen to the hospital aides, and sits down to talk with the so-called leader of the patients, Dale Harding (played in the film by William Redfield).

Yet, in the film, Jack Nicholson, as McMurphy, doesn’t have nearly the same initial impact as his character does in the novel. He casually enters the main room of the hospital, doesn’t say much, and is barely noticed by the other patients. His presence is far less disruptive in what I found to be an essential portion of the story.

And that’s not even mentioning the difference in appearance that they chose for Nicholson, which was to forego the orange hair. The star-power necessary for the film must have been a clear deciding factor (it was only a year after Nicholson made Chinatown), yet I still didn’t think of someone with Nicholson’s persona in the role when I was reading.

The issue I had with not only the way McMurphy is written in the film, but also in the way he is portrayed, is the motive behind his actions. In the novel, McMurphy, although far from selfless, seems to operate from almost humanistic, sacrificial motives. He is the Christlike figure that even the Chief admits was created by the patients on the hospital ward in order to fight the establishment, mainly because they were too weak to do it themselves.

Yet, in the film, McMurphy never seems to act under any pretense other than for his own interests. He steals a boat not to help the other patients experience the outside world, but because he wants to prove to the hospital officials that he is actually crazy so that he will stay there instead of being sent back to prison. One of the pivotal scenes in the novel is when McMurphy, in an act of defiance, punches through the Nurse’s window to get the cigarettes that were being withheld from them. Yet, in the film, he seems to do this only to quiet one of the patients that was complaining about not being able to smoke. It is an essential stab at Nurse Ratched that is completely wasted as portrayed on-screen.

The problem is also with Nicholson, who doesn’t seem to really embody the manicness of McMurphy. He has an extreme energy about him, for sure, but McMurphy as written by Kesey was such a wild force of nature that he could bring an entire room of mostly lethargic patients into an uproar. His presence is so dynamic that even while reading I felt myself being lit up by his words and actions. Nicholson is fine as far as fitting within the framework of the film itself, but when compared to the written character of McMurphy I just didn’t buy it.

The other essential character of the story, as the opposing force to McMurphy, is Nurse Ratched. As written, the character is soft-spoken and seemingly harmless, yet so incredibly manipulative that she almost seems to effortlessly run the hospital. Other than a few disruptions, the patients surrender to her will, and though she has moments when her emotions get the best of her, she almost never appears to lose the upper hand (at least until the climactic ending).

As such, Louise Fletcher‘s performance is pitch-perfect. Her pleasant, sweet-as-sugar voice serves as contrast to the sheer hatred that lurks within. The finale of the film, where Ratched nearly loses her cool at the destructiveness of the party on the ward, yet then resorts to the ultimate act of manipulation, is as devastating as it is because of Fletcher‘s powerhouse performance. She truly created one of the great villains of cinema.

Brad Dourif, who was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for this role, gives a memorably wonderful performance as Billy Bibbit. The stuttering, boyish character is essential to the story, mostly because of his tragic ending, and ironically it is really his growth throughout the story that leads him to such an end. McMurphy takes it upon himself to help Billy Bibbit, being the only positive role model in his life after being manipulated by both his mother and Nurse Ratched, and Dourif plays the character with a youthful charm. It makes the conclusion all the more sad as a result.

As far as the side characters, William Redfield plays the character Harding well, although I was upset that they excluded some of his more memorable dialogue scenes with McMurphy. Sydney Lassick is fine as the obnoxious Cheswick, as is Danny DeVito as Martini, and though Christopher Lloyd‘s character isn’t really even in the novel, he’s not bad as the character Max Tabar. All in all, though I still do believe that Jack Nicholson was miscast, the remaining actors were adequately chosen for the film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Chronology

Another potential issue with the film adaptation of Ken Kesey‘s novel is the order in which events are portrayed. One of the most idyllic scenes of the story to me were those that took place on the deep sea fishing trip. Though the trip does take place in the movie, there is not only a lack of motivation to be there in the first place (seeing in how McMurphy simply steals a bus and drives all the patients there), but also a lack of growth of the patients on the boat.

In the novel, the night before was the first moment that Chief Bromden talked to McMurphy, and he explained his bizarre yet somehow accurate views of how the mental hospital is run. On the boat that day is when they really become close, yet, as mentioned earlier, the Chief isn’t even present in this scene in the movie.

The deep sea fishing trip also represents the first cautionary move for many of the patients in the novel. Though they do willingly sign up for the trip, they are still extremely frightened to be out in the world. Yet, out there in the open ocean, as they drink beer, converse, and genuinely enjoy one another’s company, they truly feel like real people again. As the Chief remarks, they come back from the trip different people than those that left, making it the turning point for many of them. By presenting this scene towards the beginning of the film and with an entirely different basis behind it, such a triumphant feeling is therefore almost entirely absent.

The basis of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in both portrayals is that of the power struggle between McMurphy and Nurse Ratched. McMurphy begins by making a bet that he can get under the Nurse’s skin after a week, and after upsetting her by getting the patients wiled up for a baseball game (which is played out wonderfully in the film), the Nurse then gets the upper hand once McMurphy realizes that he is only prolonging his stay by being disruptive. But then, in an ecstatic moment, he gains it back by punching through her glass where she is keeping their carefully portioned cigarettes. Yet, as mentioned earlier, it is a moment that is portrayed completely differently in the novel, and without the same end result.

Another power win for McMurphy is when he fights the aides (called the “black boys” by Chief Bromden), after they try to humiliate a germaphobic patient with a delousing. But, perhaps due to time constraints, this scene is instead thrown in with the last one, which itself was barely a triumphant win for McMurphy. Essentially, the film attempts to combine too many pivotal moments into one, thereby making them each much less impactful as a result. The finale of both versions, though, is both emotionally and thematically powerful.

Themes

In the final scene of both the novel and film of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, McMurphy throws a party for the patients on the ward, inviting some girls over with bottles of alcohol. Though such an act would have been all but unheard of earlier, they willingly go along with it due to their growth throughout the story.

Nurse Ratched returns the next morning and, having witnessed the after results of the party, attempts to keep calm. When seeing Billy Bibbit in bed with a prostitute, though, she almost loses it, and though Billy (in a non-stuttered voice) at first stands up to her, she eventually demeans him by threatening to tell his mother.

Such an act, for those who know the story, leads to Billy Bibbit’s suicide, and to McMurphy attempting to strangle Nurse Ratched in revenge. The scene as it plays out in both the story and, in this case, especially on-screen, is powerfully emotional and tragic, with some incredible acting by all involved. Such a scene, though painful to witness, serves the basis of the primary themes of the story.

The thematic underbelly of Ken Kesey‘s novel is one of society against the stronger establishment leaders. The hospital ward patients in the novel, like Billy Bibbit, represent the weaker members of the world who are often oppressed and beaten down by those above them. People like Nurse Ratched are, as Chief Bromden calls it, a part of the nation-wide force known as “The Combine.”

McMurphy represents an upset to the balance, a spark that eventually ignites a flame of righteous indignation against such a force. Billy Bibbit’s suicide is proof, though, that nobody can completely overthrow the system without some casualties, and that there will always exist some oppressive force that will attempt to bring weaker-minded people down. McMurphy himself is even lobotomized after he attempts to strangle the Nurse, but the point is, as he said earlier, that he at least tried his best, and that’s more than most people do in their lifetime. And it is his influence that spreads to other members of the ward, many of whom voluntarily leave after Billy Bibbit’s demise.

Though the insightfulness of these themes are still more impactful as written, it’s hard not to at least admire Miloš Forman‘s attempts at them in his adaptation. In many ways, he falls short of full force, creating a film that often seems like nothing more than an arrogant man trying to escape from a mental hospital, but at times, such as in these final scenes, he seems to finally grasp the deeper meanings of Ken Kesey‘s work.

Conclusion

The novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and its subsequent film adaptation are both considered classics in their own right. Though Ken Kesey‘s novel grasps much deeper at its symbolically important themes, both through the perspective of its narrator Chief Bromden and its portrayal of the character Randall P. McMurphy, the film does an adequate job of at least creating the same end result.

Jack Nicholson‘s character may be different as portrayed, both looks-wise and in his motives, yet he still seems to fit the somewhat looser framework of the film, and in addition both Louise Fletcher and Brad Dourif are ideally cast. When it comes down to it, though I would personally prefer Ken Kesey‘s words to Miloš Forman‘s vision, the impact of both by the end is both tragic and thought-provoking, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is guaranteed to influence both readers and movie-watchers for generations to come.

[highlighted_p boxed=”false” center=”false”]Have you read the original One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest novel? How do you think it compares to the film? And if you haven’t read it, are you intrigued to read it?Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

David is a film aficionado from Colchester, Connecticut. He enjoys writing, reading, analyzing, and of course, watching movies. His favorite genres are westerns, crime dramas, horror, and sci-fis. He also enjoys binge-watching TV shows on Netflix.