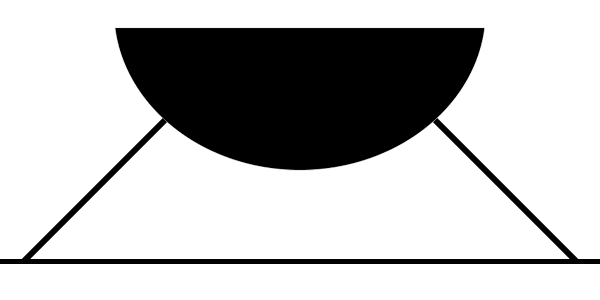

Consider the below image: a simple vector graphic depicting a carefully balanced bowl. The bowl is well-supported and stable, with two supports effortlessly and comfortably relieving our minds of any worry that the bowl may tip. This well-balanced bowl is a perfect metaphor for a well-framed shot. By following the age-old and well-established rule of thirds, having the subject and counter-subject of a shot placed in the thirds of the frame, the shot feels balanced and natural. Again, our minds are at ease: we have no worry that the bowl may tip.

But what happens if we decide to take away one of those supports? Is it still possible to balance the bowl? Possibly, but it will be immensely challenging. We’d have to try and place the support exactly in the center of the bowl’s curved bottom, and place the bowl carefully, so as not to let its contents shift or move at all, as even the slightest movement will create a weight imbalance that will cause the bowl to tip. Even if we succeed in balancing the bowl, anyone coming near it will have to tip-toe, moving with extreme care so as not to cause any vibrations whatsoever. In short, the task is next to impossible.

Why is it then that Wes Anderson, genius auteur and filmmaker extraordinaire, is able to achieve this balance when placing his subjects dead center? Why doesn’t his bowl tip, as it were?

The Camera Frame Re-imagined

The answer is simple. He does achieve balance. He just does it differently. His lighting, set dressing, production design, everything in the frame outside his subject provides not just one, but two more supports that can be placed on either side of the single support, providing an even better-balanced bowl than what we had using conventional methodology. Notice in this shot from The Royal Tenenbaums, the lamps on both extreme edges of the frame, the equal length of couch on either side of the central subject, the large area of darkness surrounding the windows on the right side of the frame balanced with the smaller area of darkness set behind the lamp on the extreme left side of the frame, and the incredible use of color, all of which come together to perfectly balance the shot. You can almost see all three balancing supports: the center, the left, and the right.

As part of his artistic style, Anderson greatly emphasizes this method of balancing his shots (center subject, left and right balance with other elements). One way he does this is by limiting the angles he uses in his camera. You’ll notice in Wes Anderson films that there is little to no handheld camera. Also, nearly all his shots are straight on at eye level; there are very few high or low angle shots. By making it clear from the very beginning of his films that the camera is a static object, the frequent tripod pans, dollying, and trucking he uses feel far more natural than they would in any other conventional film. This serves to greatly emphasize the center-focus.

The only exception to the eye-level shot in terms of Anderson’s artistic style seems to be the overhead shot, which he frequently employs as inserts. Even in these, there is still no camera tilt at all. The camera is set back, creating a wide shot that allows the framing to remain straight on while still catching the necessary action: no tilt whatsoever. Again, this serves to emphasize center, by using the objects in frame to call attention to the fact that the camera is dead-on, ever focused on a center point.

The Unseen Red Dot

Consider the above image. Imagine this is a camera frame. It looks like any other camera frame, complete with a small red dot in the middle. Of course, filmmakers typically do not use the camera’s built-in dots or other guides, and yet, Anderson seems to be constantly trying to make us “see” this unseen red dot; to call our attention to that point. Consider this shot from The Grand Budapest Hotel:

Notice that while the subjects are framed to the extreme left edge of the frame, the eye travels back and center. Why? Because everything in the frame is metaphorically “pointing” dead center. The pipes, the shelving, the lights, everything is screaming at you: “Back and center! Back and center! Back and center!” Indeed, our attention goes straight to the center, as though there were a large red dot there, shining bright. Anderson’s framing is metaphorically just as eye-catching, just as glaring for lack of a better word, as a bright red dot in the middle of the frame.

It’s almost like Wes Anderson films are the “yoga” of filmmaking: it’s all about finding the center, both metaphorically and literally. So why is this important? Simply because in making his films this way, Wes Anderson is making one of the boldest statements in cinematic history.

The Untapped Half of Filmic Potential

Let’s use a simple metaphor to show exactly how powerful a statement Anderson is making with his signature style. Ever since exclusive use of the wide shot was left behind early in film history, the camera has been free to move in order to create more compelling shots. Since then, nearly every film in the art form’s comparatively short history has entirely depended on using the rule of thirds, a filmic rule conveyed perfectly by every other row on a simple wall of cinder block bricks:

Even when the rule of thirds is not used and intentional center-framing is employed, it’s usually to emphasize a point, as shown in the concluding shots of Michael Curtiz’s timeless Casablanca:

I highly encourage you to take a moment to watch that final scene from Casablanca, and pay close attention to how Curtiz uses subtle framing choices, including a perfectly timed center framing, rendering the change almost imperceptible, and incredibly effective. As we can see in this and other examples, the very absence of rule-of-thirds-framing only serves to further cement the rule as the art form’s standard. However, what about all those other lines between the ones we use?

Strictly limiting ourselves to using the rule of thirds leaves fully half of filmic potential virtually untapped, and until Wes Anderson, nobody had really been able to think outside the box (or between the lines, as it were) in order to create a compelling style for that other half. In other words, Anderson has not only provided us with a new and compelling way to compose shots, but has created an entirely new filmic approach that will allow future directors to tap into a previously unused wealth of cinematic potential.

With each new film, Anderson further establishes himself as the great pioneer of this filmmaking style. Think back to the beginning of any new art form. The first practitioners of that art form usually ended up calling attention to the style in their work. Later, new practitioners figured out a way to use the art form more subtly: to create art that took advantage of the powerful elements of that style to convey their art, without the glaring hints that practically scream “Hey, I’m using watercolor.”

Eventually, the art form moves from the viewer noticing the form first rather than the image itself, to the viewer noticing the image first, and having to look closer in order to determine the form or style. Anderson is pioneering a completely new filmic approach, a completely new artistic style, and therefore, he calls attention to it wherever possible. Future practitioners of the “Andersonian Style” of filmmaking will be among those who are able to force the viewer to see the image first, rather than the style.

In doing this, Anderson has not only established a firm and compelling stylistic approach to filmmaking, but has also created art, in every definition of the word. His films are filmically and stylistically challenging, full of expression, intensely engaging, with shots dripping in meaning and subtext (like the unseen red dot), and in the end, simply beautiful. While art itself may not have a strict definition, Wes Anderson’s films clearly fit the bill.

Conclusion

One of his most popular films will serve as a great example for Anderson’s artistic talent. Fantastic Mr. Fox is the summation of a filmmaker’s aspirations to make “every frame a painting.” His set design and cinematography are some of the most articulate, and his films bleed the desire he feels to make each frame a work of art, almost literally. Imagine framing an enlarged film cell, picking nearly any frame from any of his films, and hanging it in your house. Chances are it would feel right at home next to a classic painting, with subtext, a focal point, and a style to rival the classic work.

With Fantastic Mr. Fox, Wes Anderson proved himself a true master, providing a realization of the perfect pairing: Anderson, the master of painting with film, and stop motion, one of the most practical filmic way to truly realize the lofty goal “every frame a painting.” Anderson took on this project at the perfect point in his career, painting us a picture that shines with all the experience he’s gained, while still providing promise of the greatness to come.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.