How UNDER THE SILVER LAKE Unearths The Male Sleaze Of The Film Noir

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate,…

“Sure, I’m decent,” Rita Hayworth says as she slides her frilly little négligée up her shoulder. Gilda, the 1946 film noir in question, spotlighted Hayworth as the ultimate femme fatale — “There NEVER was a woman like Gilda!” the posters emphasize. Hayworth’s signature role is the Platonic ideal of a noir girl: She’s vengeful and ruthless, but she also sings, dances and looks incredible in a thin, strapless black satin dress.

The overt sexualization of the “dangerous woman” archetype is de rigueur in film noir. Hayworth’s as much the main draw of 1947’s The Lady From Shanghai, for example, as Sharon Stone is to 1992’s Basic Instinct. That deeply misogynistic history, for better and worse, forms the backbone of David Robert Mitchell’s Under the Silver Lake, a whodunit-and-wheredidshego mystery that stands tall amongst our smattering of postmodern noir.

The genre recalls chiaroscuro chases, dangerous dames, fedora-tilting heroes, and seedy villains. Like the Western and the war film, a noir movie will always have one leg in the past. The crime sagas, moral complexity, and compromised heroes will always reflect post–World War II American pessimism, the great national reckoning that it’ll take more than guns to solve the world’s problems. Every shooting and beating in a noir film reflects the cold, unblinking injustice of the universe.

For centuries, the United States stayed out of any large-scale global conflict, but suddenly, twice in the span of 30 years, hundreds of thousands of American sons were sent overseas and subsequently killed in combat. Noir reflects this bitterness and chops down all moral boundaries — its heroes are wrinkled and severe, determined to win in the end no matter what the cost. And even if the gumshoe finds the whatsit, punches the baddie, and gets the dame, you have the sense that a chunk of their soul was lost along the way.

Under the Silver Lake understands the structure and history of the genre and builds like a barnacle colony, attaching to and growing on the bones of film noir. It’s a snappy, unpredictable, conspiracy-fueled thriller that feels like a hummingbird, feeding once every 10 minutes on a juicy Hitchc*ckian dolly zoom or an oblique reference to Mulholland Dr. lest it become malnourished and stop flying altogether.

Forget It, Sam, It’s Los Angeles

As our lead, Andrew Garfield plays Sam with the hunched beta masculinity of Jimmy Stewart and the sneering, straight-backed entitlement of Joseph Cotten. He’s not stereotyped or cobbled-together; he’s got shades of every film noir great from the 1940s through to the ’60s. Of course, as the film’s set in the modern day, the character’s absurd. Seeing Garfield tailing a suspicious woman, slinking behind palm trees in broad daylight without even black-and-white photography to help his cover becomes one of the film’s few charms.

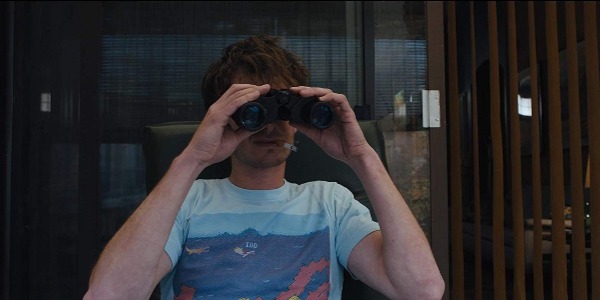

Sam lives alone in a Los Angeles apartment in Silver Lake, where he works so little that it’s a mystery how he can afford the rent. He mostly smokes, has sex with his actress friend (Riki Lindhome), and ogles his female neighbors with a pair of binoculars a la Rear Window. Basically, he’s an incel hero, like the Joker or that dude from The Sun Also Rises.

From his privileged white boy’s perch, Sam realizes that his hot-pants neighbor, Sarah (Riley Keough), has gone missing. Determined to find her, most likely to sweatily consummate his affections toward her, he spends the remainder of the picture stuck in a windy Pynchonian labyrinth of cults, secret codes and dog murderers. As far as film noir goes, it’s all very surreal.

The catch is, as I’m sure you’ve gathered already, that Sam’s an unrepentant asshole, a world-class sleazeball who’s both a chore to follow and a struggle to take seriously. Unfortunately, his perspective is the film’s perspective, so we see the world through his crass, juvenile, leering eyes. The question pervading Under the Silver Lake is a Pavlovian one of gaze: when the film shows us a woman’s posterior, does it expect us to salivate?

Who Are You Wearing?

To film noir, costumes – especially women’s costumes – are essential. Does the female lead wear an expensive leopard-print coat, as Jane Wyman does in The Lost Weekend? Or a casual bathrobe, like Gaby Rodgers in Kiss Me Deadly?

Noir women’s modes alternate between sexual and sexually subversive, while the male heroes always dress in suits. Usually, if we’re lucky, they have silly, stubby neckties to boot. The men are all business, all the time, and they treat cracking jaws and downing whiskey doubles as though it were a day job. Yet this is one category where Under the Silver Lake diverts: Sam is a slob. His wardrobe is a disaster.

And while Sam enjoys his crap taste in clothing, the female characters are hardly clothed at all. We only see his bird enthusiast neighbor (Wendy Vanden Heuvel) topless, and when he watches the mysterious, alluring deshabille of rich girl Sarah, he’s mostly staring at her bum – which means that, because we share Sam’s point of view, so are we.

There are two camps of thought on Under the Silver Lake: That it’s 1) playing these scenes straight, or 2) that it’s satirizing them. I choose to believe that Under the Silver Lake is not intellectually malign enough to seriously expect us to side with Sam, a lazy, narcissistic, pesky creep.

I want to believe that the film is then a tour through film noir of yore, a journey to systematically convince me, one point at a time, of all of the genre’s shortcomings, the male gaze first and foremost.

Live Sexy, Die Sexy

The male gaze is that tendency to objectify women and imagine them less as human and more as art to be observed and, perhaps, touched. Think of the introduction to Carmen Sternwood, played by Martha Vickers, in Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep. Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart) admires art on the wall, then looks at the stairs and sees Carmen, subconsciously moving from one item of art to the next. For her first few shots, the camera frames her from the bottom of her rather short skirt to the top of her head, always keeping us aware of her revealing outfit. And for god’s sake, her name is Sternwood.

The ass shot was not yet common cinematic rhetoric, but it was firmly established in time for Under the Silver Lake. I want to read the ass-ogling scenes as necessary inventions by the script (also by Mitchell) to set up a male-protagonist synecdoche whom it can then tear down. I want the naked woman across the street to not be a prop to the action, but she is. I want Millicent (Callie Hernandez) to survive, to not die in a sexy pose in a reservoir, but the film has other plans.

Imagery aside, Sam’s life is phallocentric – a party he attends extends to him a large cherry ripe for Freudian readings, he masturbates as he tries to find hidden messages in music, and he limply holds a pistol for the majority of the finale, as though it’s an extension of his own feeble member and merely flaunting it will help him find his sexy-pants neighbor. Oh, and there’s the scene where he literally imagines her half-naked on the side of the pool, barking like a dog.

Mitchell can’t lead us through his mucky, muddled material, and it falls into the sticky trap of indulging in the very behavior it’s possibly trying to mock. It’s the same mistake David Fincher made when he directed Fight Club, another male-centric neo-noir – the movie isn’t detached enough from the lewd, undressing power of the male gaze to comment on or to rationally analyze it.

Alfred Hitchc*ck’s Vertigo, predating Under the Silver Lake by over 60 years, tackled this same subject and with 90 percent more class and 100 percent more scenes where Jimmy Stewart talks about women’s brassieres. Hitchc*ck’s story of lovestruck detective Scottie (Stewart) destructively fetishizing and pursuing the woman of his dreams (Kim Novak) laid bare the malevolence of the male gaze.

And because this was 1958 and Hitchc*ck’s tendencies were more romantic than perverse, Novak’s lot in all this is surprisingly tasteful. That’s to say, she’s never naked, and Scottie spends more time staring at her face and touching her hair than anything less Puritan. The film’s more about the act of looking than what’s being looked at. Under the Silver Lake is decidedly… ahem… vertiginous. It wants to be a Hitchc*ck film so badly that in one particularly eye roll–inducing scene, partying twentysomethings stand and drink on Hitchc*ck’s grave in the Hollywood Forever cemetery.

Mitchell’s film begins with a shot of a woman cleaning graffiti off a wide glass window. She’s got an ample chest and a loose shirt, and when the camera swivels around to reveal that we’d been sharing Sam’s eyeline, one wonders whether he was looking at the graffiti or the woman’s breasts. Aren’t we leering just the same as he is? Is the film not facilitating this relationship between audience member and breasts?

It’s the same problem that spawned from Fight Club: whether or not that film tries to take Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) to task for his beliefs and phallus-forward doctrine is irrelevant. Too much in the film glorifies sweaty machismo pummelings and groovy anarchism, even if it’s intended to be satirical. Maybe the film is a takedown of masculinity. But that the film can even be interpreted to the contrary points to a fundamental flaw in its direction.

Roger Ebert said it best in his initial review of Fight Club: “Although sophisticates will be able to rationalize the movie as an argument against the behavior it shows, my guess is that audience will like the behavior but not the argument. […] The images in movies like this argue for themselves, and it takes a lot of narration (or Narration) to argue against them.”

Biker Chic Feminism

Noir was and always will be a male-dominated genre. The problem is its directors. Recently, two female-centric noirs, Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Aaron Katz’s Gemini, attempted to put the women’s characters before their bodies. In The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, the more prestigious of the two, the women wear sleek biker clothes and pose with guns, but male-directed skin-tight leather–clad fem-dom worship isn’t exactly feminism.

Similarly, Gemini, a 2017 indie darling, stars two female leads and gives them the floor. This one’s another missing-woman movie, wherein Zoë Kravitz plays a famous actress (what a stretch) who does the missing, and Lola Kirke plays an assistant, Jill LeBeau (what a loaded last name – lesbian undertones, anyone?), who does the finding. But why do we care that Kravitz’s character is missing? Because she’s a famous actress. Because her appearance has value. Because sex sells. For all the same reasons, Kravitz plays her in the film. It’s a twisted cycle that the movie never tries to wrestle with, settling the feminist score with “look, Zoë Kravitz wears sweatpants!” The femme fatale has entered the slacker age, finally.

But these films’ contribution to the noir genre is the focus on women’s psychology and mental processes. Kirke might be dressed like a Tron character by the end of Gemini, but she’s now playing the Humphrey Bogart role. She’s completely unlike every other female character in film noir — “there NEVER was a woman like Jill!” the poster should have declared.

It’s odd to laud Gemini for being a standout in a genre where women are frequently treated as props. Yet in Under the Silver Lake, which tries to condemn misogyny and elevate women, the women exist solely for the function of the narrative and the whims of its main character. They pop up, Garfield uses them for a scene or two, and then they either permanently exit the narrative or are killed, usually horrifically.

Sam hates women, but he’s also a conspiracy nut, and hell, he’s probably a flat-Earther, and he’s driven by that singular, haunting, privileged paranoia of well-off, lonely, lazy white men. The rich elite are trying to silence him, the government killed his hot neighbor and there’s an owl-faced woman who tries to stab him in his sleep. The wool is over everyone’s eyes, and Sam’s the only one who can make the world see the truth, even if he has to tackle a kid in the street and shove eggs into his face.

The Stuff That Genres Are Made Of

Maybe the genre is beyond rehabilitation. Every couple of years, a legitimately interesting, incisive filmmaker like Ana Lily Amirpour will bring its corpse out and make it dance for our amusement and for piecemeal international returns. It’s a dead genre, like the Western and the disaster movie – the biggest noir movies now are aftershock in the wake of its 1950s peak.

It isn’t vital anymore. Nobody cares about noir. We’ve learned the world is morally ambiguous, that good men don’t exist, that everyone’s got a bitter, rotten soul, that anyone looks cooler smoking cigarettes. Hell, we’ve had too much of that narrative, which is why the sanitized, superhero-forward, binary good-and-evil cinema of Marvel has dominated the multiplexes. I think it’s safe to say the U.S. has moved on.

Even Sam, the quintessential noir protagonist, feels out of time. Sam is listless, a cypher. He’s someone who can never exist in the real world – he’s so behind on his rent that he shouldn’t be able to pay for the two Old Fashioned’s he orders one night. That he might not have a place to sleep in a few days seems only his faintest concern as he pursues lead after lead across L.A.

Twenty- and thirtysomethings now have everything to worry about. Where will our next meal come from? How can we pay off student loans and afford to do laundry? Where do we fit into the world if it isn’t made for us in mind? For a movie that supposedly updates the film noir for 2019, Under the Silver Lake comes up embarrassingly short.

Watching a creepy, dorky white dude try to track down a hot blonde girl he wants to bone just doesn’t hold much meaning for me. I think about the film’s perverse attitudes toward women and then remember that tagline – there never was a woman like Gilda. Beautiful, deadly, vengeful, controlling, capable of slapping men around and teasing them with low-cut dresses and curvaceous bodies.

The tagline’s bullshit, of course. There have been and continue to be plenty of women like Gilda, and there are even some who come with sensible outfits. But in noir movies, they’re all loved-up eye candy; the noir woman wouldn’t drink hard and solve murder cases downtown. She’s more likely to be found dead in a sexy pose under the Silver Lake.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate, head of the "Paddington 2" fan club.