“F*ck Superheroes”: Trope Maintenance Vs. Trope Subversion In DEADPOOL 2

Tessa is a writer living in Boston, where she spends…

Let’s get this out in the open: if you go to see Deadpool 2 when you are not the type of person immediately inclined to like Deadpool 2 (having had plenty of time to come to terms with disliking Deadpool 1), you have truly no one to blame but yourself. I have to take responsibility for that much.

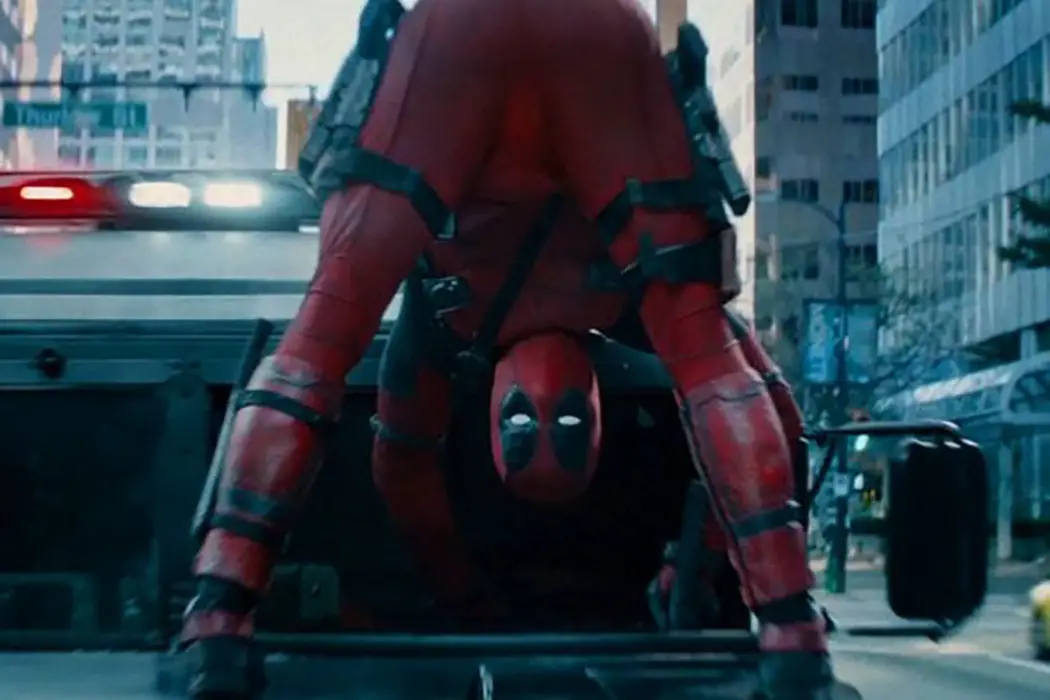

Knowing this, criticizing the Deadpool franchise almost feels like a moot point. You don’t find the idea of Ryan Reynolds running around talking about his dick to be funny? There are plenty of other movies to watch. But it’s a generous oversimplification to claim the only factors going into Deadpool 2 ’s reception is whether the viewer has a sufficiently raunchy sense of humor. There’s something else going on under the surface, something that feels sometimes clunky and sometimes sneaky, and which has been happening more and more frequently in popular entertainment.

Deadpool 2 is the most recent, and to my mind, most egregious, example of a mainstream film figuring out that it can benefit from appearing subversive, without needing to put in the creative work of fulfilling this promise.

Derivation Under the Guise of Boundary-Pushing

If the filmmakers demonstrate awareness of genre conventions (in this case, by having the protagonist break the fourth wall to mock of them), they can double down on these same conventions, and still leave the impression that some kind of meta-critique has taken place. This allows studios to sell the exact same stories without the need for real creativity, while also implying the self-referential mockery is a reflection of actual innovation.

What does this mean in practice? Well, Deadpool 2 doesn’t need to push any boundaries; it spends enough time saying it’s pushing them. This is how we get scenes like the one in which Vanessa (Morena Baccarin), Wade Wilson/Deadpool’s girlfriend, is murdered in her home by a group of mobsters who have come to attack her boyfriend. This is immediately followed by the opening credits sequence poking fun at the audience’s imagined reaction to Vanessa’s death (think text phrased along the lines of, “Starring, ‘Wait what? Did they just kill her?’” ).

If you’ve watched many superhero movies, let alone picked up a comic book, the idea that Vanessa would be immediately killed to prompt her boyfriend’s emotional journey should not be shocking. Far be it from me to gatekeep nerds, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that, in this case, the filmmakers themselves don’t know what they’re talking about–a suspicion solidified by the writers’s admission that while writing the script, they weren’t familiar with the trope of fridging women (and that is what this is, regardless of a deus ex machina-laden ending that only serves to make the whole romp feel pointless).

This opening gives a pretty direct indication of how the rest of the movie will unfold: the same tired tropes being grotesquely rehashed, but with a layer of violence and absurdism slapped on top to trick amiable viewers into believing it’s all somehow subversive. It’s kind of strange to remember this franchise is marketing itself as an alternative to bloated, earnest superhero blockbusters, considering the actual movie is chock full of the exact same beats and archetypes as any of its contemporaries.

The Potential for Constructive Parody

I have a long sad history of following superhero stories, and I’m familiar with their limitations (I am also a member of the unfortunate minority of people who have been invested in X-Force and X-Factor, which makes this movie especially tragic for me–please drop me a comment if you understand why they renamed Shatterstar “Rusty,” because I’m still trying to unpack that). The truth is, I really like genre parody, especially when it comes from within the overlap of critical viewing and genuine affection. I know this is possible, because it’s been done repeatedly and hilariously in the horror genre, with movies like Cabin in the Woods, Shaun of the Dead, and What We Do In The Shadows.

What would it take for Deadpool 2 to be a little closer to something like Cabin in the Woods, which is both a genre movie and a genre parody? Cabin does a few things that works in its favor: like Deadpool, it has a character who notices and comments on tropes, but unlike in Deadpool, the existence of these tropes is then given an explanation, justifying their right to appear; it delivers as a horror movie in its own right, with scary monsters and a genuinely compelling setup; and it concludes with a solution that only makes sense because the characters understand the narrative in which they’ve been placed. In short, the filmmakers behind Cabin in the Woods make fun of horror, but they don’t punish fans for liking it. It’s clear that they like it, too.

Beyond Parody: Trope Criticism in Logan

We’ve even seen something close to this happen in the Marvel Cinematic Universe recently, albeit not within a comedy. Deadpool 2 opens with the line “Fuck Wolverine,” which is a bit of an unfortunate choice–by pulling the Wolverine franchise into the mix so quickly, Deadpool invites a comparison that can only highlight its own weaknesses.

Deadpool 2 and Logan have some obvious similarities. They’re both R-rated, allowing their characters to curse and participate in more extreme violence; they both center on grief-stricken protagonists, who must hold themselves together to act as surrogate father figures; both films canonically acknowledge the existence of superhero comics and fandom; and they both reach an emotional climax when the unwilling hero decides to sacrifice himself to protect someone more vulnerable (although Logan, unlike Deadpool 2, makes this sacrifice stick).

Logan isn’t perfect, but it does make some real strides as a superhero movie for adults. It manages to feel adult not just by ramping up the violence, but also by folding the emotional ramifications of that violence into the script, so the long term effects of trauma become a part of the story’s makeup. That’s a fairly bold choice for a genre that relies on cartoon violence and fight scenes. Stressing the impact of lifelong violence was also probably only possible because Logan was Hugh Jackman’s final appearance as Wolverine. There are only so many action sequences you can squeeze out of a character, after convincing your whole audience that every instance of violence is further destroying his ability to function.

Unfortunately, Deadpool 2 can’t really benefit from this groundwork, because it’s not really interested in looking for new ways to play with its story. It would rather capitalize on what shock value it can manage, but that only works if its language, violence, and depiction of sex are sufficiently shocking (and it’s really not–I know what a strap-on is). There are some genuinely fun moments –Zazie Beetz is great as Domino, and there’s a joke at Deadpool creator Rob Liefeld’s expense that gave me a good, surprised laugh. I only wish these positives didn’t get buried in an avalanche of formulaic smugness.

Lampshading Shortcomings Across Media

At this point, I have to make one more confession about media I’ve consumed: I am not proud to say it, but I watched the entire last season of The Bachelor . For those of you lucky enough to have never staggered drunkenly into Bachelor Nation, let me catch you up. This most recent season was notable for its controversial finale, during which Becca, the purportedly winning contestant, was dumped on air, resulting in the documentation of her real time breakdown. The cameramen followed her through her apartment, ignoring her continual pleas for privacy, capturing her from a distance as she tried not to weep.

I remember watching the finale and feeling shocked, not at the exploitation of the candidates ( The Bachelor is exploitative in the best of times), but at the show’s apparent willingness to throw itself under the bus. We all know The Bachelor is exploitative, but could they possibly recover after making this so obvious? Was the show finally allowing itself to implode?

The answer, of course, was no. The Bachelor is a reality show, and it thrives on controversy. It heavily promoted its own shock value, encouraging viewers to catch up and decide for themselves whether the finale went too far. During the post-finale interview, the host congratulated the women on their strength, and the studio audience nodded along, apparently soothed that the cruelty was acknowledged (on the part of the bachelor himself, if not on the part of the studio). As long as this works, reality TV will never, ever have to change its formula.

Modern entertainment has been learning how to foreground its own failings, point at those failings, and receive applause from willing audiences for doing so. Works of fiction might have to go about this more subtly than reality television, but it’s ultimately the same process. If a character can criticize flawed storytelling as it unfolds, the studio can signal that they’re “in on it,” and forestall more serious criticism from viewers. But in the case of films like Deadpool 2, the studio isn’t saying “We understand the problems with these movies and we’re working on them”; it’s just saying, “We understand the problems, so please don’t bother pointing them out.”

There’s a scene in Deadpool 2 in which Wade is visited by a vision of his dead girlfriend, who looks at him in concern and tells him, “Your heart’s not in the right place.” This line is meant as vague foreshadowing, but it rings out like a miserable summation of a franchise that’s squeezed all the fun out of its material, but hasn’t finished squeezing yet.

How do you feel about Deadpool’s position as a subversive hero? Is the film’s self-referential nature satisfying, or should it have pursued a more original story? Let me know what you think!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tessa is a writer living in Boston, where she spends her time eating falafel and falling asleep on public transportation. Her greatest personal goal is to learn how to allow someone to dislike horror films without trying to convince them they just haven't seen the good ones yet.