Time is our life, the very material of our existence. We save it, waste it, wish in turn that we had more of it or that it would pass more quickly. Despite its centrality, our definitions of the concept are vague and circular. Functionally, we know exactly what it is, but we can’t say what comprises it or makes it work. The mystery of time is a universal human experience, and as with all universal experiences, we’re compelled to make and watch films about it. This series of articles will focus on a genre that more than any other captures our relationship with it: the time travel movie.

Why time travel? A confounding aspect of time is our feeling of being trapped in it. Our pasts are gone: we can’t go back to our happiest moments, and we don’t get do-overs for the things we regret. Our futures are black boxes – while we can predict certain things with accuracy, we don’t know what is going to happen to us, good or bad. The wish to be able to break free from the prison of the present moment finds expression in time travel fiction.

A Brief History of Time Travel

Since time has existed literally always, you’d think that time travel as a fictional device would be very old. This isn’t the case – although many authors throughout history imagined the past and future, it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that stories about actually visiting other times begin to pop up. Two well-known examples are Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, in which Ebenezer Scrooge is taken on a ghost-guided tour of his past and future, and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, in which a young man receives a blow to the head and ends up in medieval England.

The first major work of fiction to describe time travel by technological means was The Time Machine by H.G. Wells, a landmark not just in science fiction but in our scientific understanding of time. At the beginning of the story, a character known simply as the Time Traveler describes time as the fourth dimension, a radical idea in 1895. Although mathematicians had conceived of the notion of higher dimensions, they were usually considered to be abstract values – mathematically useful, but with no real-world representation. The Time Machine brought the idea that time was simply another spatial dimension into society’s collective imagination. Wells’ fantastical assertion would soon become scientific orthodoxy: in 1907, Hermann Minkowski formalized the idea of spacetime, which would become the basis of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Beginnings on Film

Film, in its infancy at the dawn of time travel fiction, took a while to catch up. The first movie portraying time travel came in 1921, a silent adaptation of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Nearly all of the early films that embraced time travel cribbed their stories off of either Connecticut Yankee or The Time Machine – the bulk of the action was in the distant past or future, and time travel was simply a means of getting there. It wasn’t until the seventies and eighties that filmmakers began to experiment with more innovative narratives that embraced the complexities inherent in traveling to the near past or future, resulting in touchstones like The Terminator and Back to the Future.

There’s a reason the time travel movie took so long to come of age – these stories are difficult to come up with, let alone render coherent to the audience. Time travel creates paradoxes, causal contradictions that have to be handled in a logical way. On top of that, filmmakers need to invent mechanisms of time travel that are believable, if not scientifically plausible. Throughout this series, we’ll look at the different ways in which filmmakers tackle these problems and use them to create unforgettable stories.

The Time Machine (1960)

To cap off our introduction to time-travel cinema, let’s take a brief look at the first film adaptation of the story that started it all, prolific sci-fi director George Pal’s 1960 take on The Time Machine. This will provide some perspective on where the genre started and how far it’s come. This was Pal’s second adaptation of a Wells story – he also directed War of The Worlds in 1953.

In this version the time traveler is imagined to be H.G. Wells himself: played by Rod Taylor, who seems a little too square-jawed to be a reclusive inventor, but I’ll allow it. The film begins with a crash course on time given by our prospective time traveler to a skeptical audience of intellectuals. Even though this happens in the novel as well, the explicitly pedagogical nature of the scene gives the impression that even sixty-five years after the publishing of Wells’ book, time travel was still a novel idea to the average moviegoer.

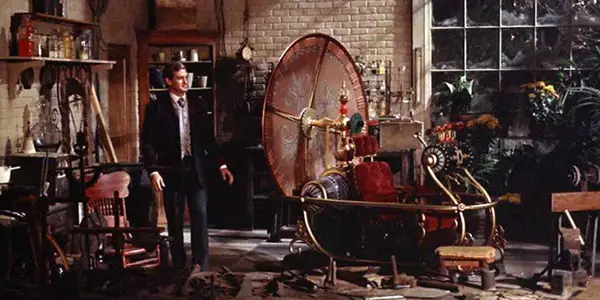

After a test run with a miniature version fails to impress his dinner guests, H. George hops into his unnecessarily ornate time machine (no expense spared, apparently) and heads to the future, eager to find a brighter tomorrow. His stops along the way reveal the opposite – an increasingly bleak state of affairs, as mankind invents increasingly efficient means of self-annihilation.

Wells wrote the book as a warning against mankind’s destructive tendencies – Pal’s film confirms that his fears were justified. The time traveler’s three stops portray both world wars and nuclear panic of the Cold War, events more horrible than could have been imagined at the time of the novel’s writing. Narrowly escaping an atomic detonation, he arrives in the year 802,701 to find a society of suspiciously young pastel-robed blondes called the Eloi, peacefully eating fruit and hanging out. Not to spoil a hundred and twenty year old story, but the Eloi are actually the food supply of the subterranean Morlocks, a snarling and furry but mechanically capable offshoot of the human race.

In keeping with the prevailing tone of mid-century sci-fi, the film ends on a much more optimistic note than the novel, in which the time traveler witnesses the end of life on earth and then never returns to the future. Having defeated the Morlocks, movie H.G. Wells returns to the future with three books to help bring the Eloi out of their intellectual dark age.

Even though The Time Machine is one of the better examples of sixties sci-fi, it feels shockingly primitive compared to films of other genres from the same era. Films like The Apartment and Psycho, both released the same year, hold up flawlessly where Time Machine now elicits more chuckles than genuine thrills. One obvious reason is that visual effects weren’t yet sophisticated enough to create convincing sci-fi worlds. While The Time Machine’s visuals are good for their time, it’s still difficult for actors flailing their arms in blue makeup and furry wigs to feel menacing. Still, Pal was taking steps forward – the film scored a visual effects Oscar for its innovative use of time lapse.

On top of the technical challenges, science fiction wasn’t yet considered to be as serious as other genres, usually relegated to lower-budget B-movie productions. Studios underestimated the scientific understanding of audiences, feeling the need to over-explain concepts with on-the-nose dialogue. In Pal’s The Time Machine we see sci-fi in its adolescence, still hampered by the genre’s problems but striving for something better. It remains the definitive film version of Wells’ novel, considered to be much better than Simon Wells’ 2002 attempt. Most relevant to our discussion here, it brought time travel back into the pop cultural landscape, setting the stage for the ascension of the time travel movie.

Instead of going through the major time travel movies in the order of their release, I’m going to pick and choose films that showcase different versions of time travel, hopefully hitting the full gamut of what the genre has to offer both narratively and thematically. Hope you’ll come along for the ride. Welcome to Time Crisis.

What is your favorite time travel movie?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.