Theo Angelopoulos And The Sea

I've been a film lover since being traumatized by "The…

What if I told you that one of the greatest filmmakers was someone whose movies you cannot see? A filmmaker who spoke for the sorrows and joys of the entire Greek nation and humanity? He’s a direct product of his country and generation, whose work is boundless and timeless. A filmmaker who had won the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion and the Palme d’Or at Cannes, an award he had been nominated for four times prior. A filmmaker with three movies in the top 100 of Letterboxd’s Top 250 International Films. A filmmaker whose focus on wars, refugees, and borders is still painstakingly relevant today.

Theodoros Angelopoulos is this filmmaker. He is one of the most accomplished and distinguishable directors to ever get behind the camera, a cornerstone for slow arthouse cinema. But despite living in an era where we have access to international and underground films at our fingertips, his works are not readily available to the U.S. on physical media or on any streaming service. It is worth asking why this is.

I first encountered Angelopoulos’ movies in college, right at that age when, as a film lover, you realize there is a whole world out there of great cinema waiting for you to discover it. My school library had one copy of “The Travelling Players,” a film I had read about, but I did not know a single person who had actually seen it. I started watching it late one rainy afternoon, not planning on finishing the 224-minute film in one sitting. I planned on stopping halfway through to go grab dinner or save the rest for another day. But once the film began, I found myself completely under Theo’s spell. It was not until the film ended that I realized I had been sitting perfectly still the entire time, my eyes transfixed on the screen, never stopping for dinner. It is that rare type of filmmaking that is so good, so invigorating, that it has the power to make you forget to eat.

To better understand Angelopoulos and his impact on world cinema, I spoke with his biographer and good friend, Andrew Horton. An American, Horton moved to Greece in the sixties, where he worked as a college professor and film critic. 1975 saw the release of “The Travelling Players,” a nearly four-hour slow-paced epic that chronicles the lives of a traveling theater troupe for over a decade, from the beginning of World War II through the Greek Civil War. Angelopoulos shot the film in secret during the Greek junta dictatorship.

Horton describes his first time seeing “The Travelling Players” as a cultural phenomenon, not just for its artistry but also for its representation of Greece. “It was told from the Leftist’s point of view, and it was giving us Greek history the Greeks had suppressed because of the dictatorship… I’ve never been so touched by how movie theaters were just packed; everyone going to see this film,” said Horton.

In this first of many masterpieces, Angelopoulos developed a unique style of filmmaking unlike any of his predecessors or peers. He designed long and elaborate tracking shots and would often shoot entire scenes in one take. Some of these longer scenes in “The Travelling Players” often feel like standalone shorts, telling self-contained stories that are one small piece of the film’s mosaic whole. These long shots capture the peaks and valleys of the Greek landscape and the highs and lows of the Greek people, combining hushed and dramatic monologues with moments of song and dance. The result is a hypnotic effect on the viewer without the usual feeling of drowsiness from watching such long takes. The common complaint about Angelopoulos is that his movies are too long and tedious. But if you are patient enough to stick with any one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s movies, Angelopoulos should be a walk in the park.

Another staple of Angelopoulos’ aesthetic is his collaboration with cinematographer Giorgos Arvanitis. Together they showed a Greece that was not always scenic and sunny, but a cold, somber country where the fog is so thick one cannot tell where the earth ends and the sky begins. To the average American viewer, the result is an almost unearthly depiction of this corner of the world.

“The Travelling Players” was Angelopoulos’ third feature and first film to reach international acclaim. Throughout the seventies, eighties, and nineties, he would direct such films as “Landscape in the Mist,” which won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and “The Suspended Step of the Stork,” starring Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau. He stuck to his visual style, continuing his use of prolonged tracking shots, and often interpreted ancient Greek text into contemporary stories, making the old seem timely. “At the heart of so many of his films is the story of Homer’s Odyssey … you’ve been through a war, and now you’re trying to find out what is home and can you get there?” Horton said.

Horton’s relationship with the filmmaker grew over the decades. “He appreciated me as the crazy American who could understand him.” Horton told me that whenever Angelopoulos had a new film for him to see, he would rent out a theater and give private screenings.

Angelopoulos’ “Eternity and a Day,” considered his magnum opus, premiered at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Palme d’Or. It tells the story of a dying writer (played by Bruno Ganz) who has grown tired of living. He is kept company by memories of his deceased wife and spends his last day on Earth searching for the meaning of his existence. The writer befriends a homeless refugee played by 10-year-old Ahilleas Skevis, credited only as The Child.

Skevis had no experience acting before. He and his family had immigrated to Kryoneri, Greece, when he was just 7. He says he was out riding his bike through the town square when Angelopoulos’ casting director, Alexandros Lampridis, spotted him. Hearing Skevis talk about his experience shooting “Eternity and a Day” and working with Angelopoulos can only make one appreciate the greatness of this director even more. How he could make a film so mature and ambitious, about life and death, youth and old age, and yet tell it with such simplicity and with such a heavy heart that someone as young as Skevis was at the time could understand. Skevis often refers to Angelopoulos as “the teacher” and says he acts as a guiding light to this day.

“This man was a magical creature, a saint of the art. I immediately felt a great sense of trust, that he was like a second father,” Skevis said. “He taught me every day to interpret life correctly.”

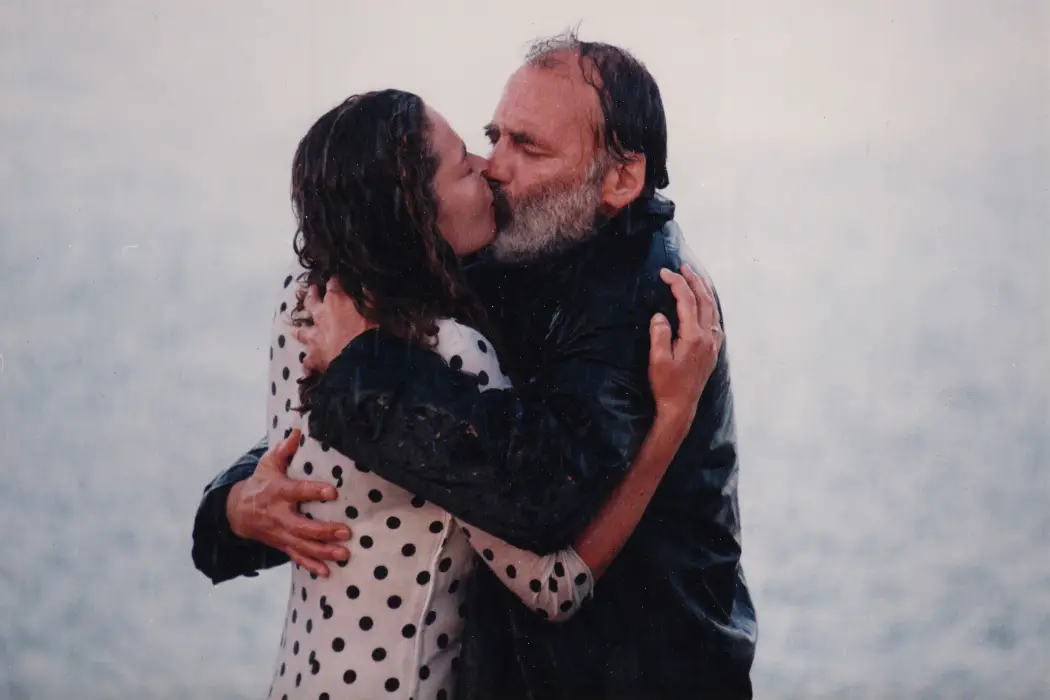

One motif that reoccurs in Angelopoulos’ films is the sea. In “The Travelling Players,” there’s a scene where a Greek family is cornered by British soldiers on a beach. The sea prevents them from escaping. Throughout the film, several scenes use the sea in this way, preventing characters from pushing forward. In “Eternity and a Day,” the sea is a doorway. It shows the possibilities of what’s ahead, as far as the eye can see. “The Travelling Players” was made by a younger, beaten-down Angelopoulos who had lived through so much war and had seen pain, like Skevis’ Child character. In “Eternity and a Day” he’s older, just as anguished but far less cynical.

Angelopoulos’ films often told stories of refugees and other victims of war, from the Greek Civil War to other conflicts that plagued the Balkans throughout the nineties. The images in his films mirror what we are seeing on the news every day in Ukraine. “Angelopoulos, as a great Greek, understands the concept of asylum very well and turns it into poetry, emotion, expression, and truth,” Skevis said. To claim that his films are no longer important is simply untrue.

Back in February of 2021, Angelopoulos supporter Martin Scorsese wrote an essay about Federico Fellini. In it, Scorsese says masters like Fellini, Stanley Kubrick, and Ingmar Bergman “would eventually recede into the shadows with the passing of time.” While these auteurs of the past may not be as popular as they once were, their work and legacies are still celebrated by today’s film enthusiasts. Young film lovers can easily access “La Dolce Vita” or “The Seventh Seal” on several streaming platforms. But there is a long list of filmmakers, whose greatness is parallel to the likes of Fellini, whose work is not readily available. Angelopoulos is undoubtedly the most acclaimed of them. His fans must either buy unreasonably priced DVD boxsets or torrent his films illegally.

In one of Angelopoulos’ more widely distributed films, “Ulysses’ Gaze,” Harvey Keitel plays a filmmaker who tries to track down the last existing reels of the first film ever made in the Balkans. What the film shows is unknown, but Keitel must find the reels because they are a part of history. It is ironic considering “Ulysses’ Gaze” is a film that also needs saving. Several scenes from the DVD are riddled with scratches and streaks. I fear that in 40 years, I’ll be the old man who travels to Greece to save the last copy of one of Angelopoulos’ other movies.

Angelopoulos was struck and killed by a motorcyclist on the set of what would have been his last film, “The Other Sea.” He was 76 years old. A month before his death, Horton had visited him on set. Angelopoulos said that he would stop directing after this film but told Horton that they should write a comedy together. While his films had a current of melancholy running through them, Horton said Angelopoulos often spoke of the importance of comedy and joy. “The comic spirit didn’t mean just laughter but a sense of how to get through hard times,” Horton recalled him saying.

As important as it is to celebrate and support new voices in cinema, we should also remember and preserve the work of those who came before. Horton says he constantly receives emails from people saying that Angelopoulos’ films have changed their lives and that they are looking for ways to see all of his life’s work. When asked about Angelopoulos’ legacy, Skevis told me, “We often say pain can be endured, but memories are eternal. He is the man who passed through my life, and for me, is now immortal.”

If you would like to watch Theo’s movies, please check your local library. Also, retrospectives of his work are held in revival houses all over the world.

Have you seen any of these? Already a fan? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I've been a film lover since being traumatized by "The Shining" at age six. I graduated from Temple Film School and live in Boston now. I am interested in director-driven cinema and exposing the public to lesser known auteurs. I also do private script coverage.