Unmaking Of An Epic: The Production Of HEAVEN’S GATE

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art,…

The New Hollywood – The End of an Era

By the late 1970’s, the film industry had undergone a renaissance. The New Hollywood movement made it so the directors were the “auteurs” of their films, and artistic freedom reigned over modern movies. Unfortunately, all great things must come to an end, and the demise of The New Hollywood movement was on the horizon. At the end of the 70’s, studios were convinced that the directors of The New Hollywood were incapable of failure; that is until they let their own projects get away from them.

All the big names of this period seemed to have fallen on their own swords with big budget flops. Martin Scorsese stumbled with New York, New York, Peter Bogdonavich made a major misfire with At Long Last Love, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer was a bomb, Dennis Hopper had lost his mind while making his passion project The Last Movie, even Steven Spielberg’s bombastic WWII comedy 1941 performed poorly. These projects showed the studios that maybe even the wunderkind directors were capable of failure. As the director’s era was coming to a close, however, it was Heaven’s Gate that would be the major nail in the coffin.

Given the talent and resources, Heaven’s Gate should have been everything that it was intended to be – an American classic on par with epics such as Gone with the Wind. However, it seemed like the planets were aligned to destroy any chance of success that Heaven’s Gate could have seen. For years after its release, the film was known as one of the biggest flops of all time. It was an unequivocal box-office disaster that dealt critical damage to Michael Cimino’s career as well as its studio United Artists, who nearly went bankrupt after the production.

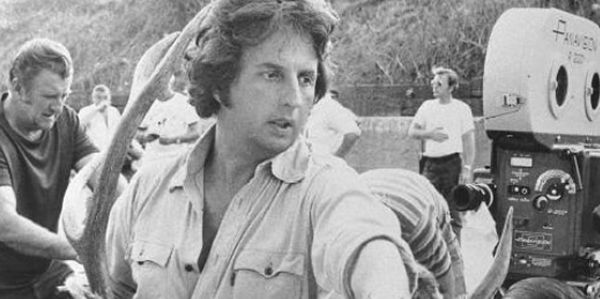

With all of this firepower why was Heaven’s Gate such a massive failure? If you divide the many contributing factors, the explanation is diverse as much as it is simple. However, the nerve center at the heart of this cinematic debacle boils down to a director who would not let anything stand in the way of his vision, and the studio that shot itself in the foot by signing the director a blank check. But it’s not as simple as that – the story of an overly ambitious director is merely the first chapter when chronicling the tumultuous production of Heaven’s Gate.

United Artists – The Studio That Gave Too Much

At this time, United Artists was lead by the management team of Arthur B. Krim and Robert B. Benjamin; however, a dispute with their parent company, Transamerica, (a conglomerate holding company) caused Benjamin and Krim to leave United Artists to form Orion Pictures. United Artists formed a new management team with two younger (and comparatively inexperienced) executives named Steven Bach and David Field. These two would go on to oversee the production of Heaven’s Gate, and inevitably rattle sabers with Cimino over the extremely taxing production.

Hoping to dash the impression of inexperience, Bach and Field wanted to inaugurate a new franchise or poster filmmaker to their studio. It was great that United Artists was home to the Rocky films, multiple Woody Allen projects, as well as the James Bond series, but these projects were inherited to the studio. Therefore, Bach and Field were determined to make their mark by delivering their own original filmmaker, and that turned out to be Michael Cimino.

After seeing an advance print of The Deer Hunter, Bach and Field were nonplussed by the overwhelming intensity of the film. The experience was summed up by Bach: “we want to be making pictures with this man, this is a potentially great filmmaker, and we want to make pictures with him, so let’s see what he would like to make”. Cimino’s next project was Heaven’s Gate, which he said he could bring in for the average cost of $7.5 million, but was instead issued a budget of $12 million. Most important to Cimino and the reputation of United Artists, though, was that he was given final cut of the film.

Casting – Warning Signs from the Start

During pre-production, Cimino had insisted on casting Kris Kristofferson and Christopher Walken, which United Artists had agreed upon. The next question: who was going to play the female lead? Due to their high status at the time, Diane Keaton and Jane Fonda were considered (who both turned down the role), but Cimino insisted on French actress Isabelle Huppert.

The concern with Huppert was her English, and after hearing her read, Bach and Field told Cimino she was wrong for the part. But Cimino decided to cast her anyway. When Field approached Cimino agreeing to forget the incident if it was reconciled within 48 hours, Cimino told Field to go f himself and hung up the phone. Telling your boss to go f themselves is one thing, but the principal that concerned Field was a matter of trust. Cimino said Huppert could read, but she obviously could not. Plus, the executives said no to casting Huppert, and Cimino cast her anyway. There wasn’t one foot of film shot for Heaven’s Gate, but egos were already clashing.

After building town-sized sets, curating 19th century locomotives, and casting roughly 1,200 extras, principal photography of Heaven’s Gate began. After six days, Cimino was five days behind schedule and had spent $900,000 for a minute of what he deemed usable footage. Two weeks later, shooting was ten days behind schedule, fifteen pages behind on the script, and had two hours of footage with only three minutes of usable content. At this rate, Heaven’s Gate was costing a million dollars a minute.

Trouble Shooting

With so much time passed, so little useful footage, and being behind schedule by several days, United Artists knew that this wasn’t going to be an easy production. But why was Cimino so far behind? Cimino didn’t just want to make an American classic, but the best American classic. His attention to detail and period accuracy went overboard. Not to mention that he asked for take after take on every scene; so many that one entire day of shooting was devoted to filming a single shot. Fifty-two takes later, one second of film was shot that day.

Huppert, Kristofferson, and Walken weren’t the only stars of Heaven’s Gate; Joseph Cotten, John Hurt, Jeff Bridges, Sam Waterston, Tom Noonan, Mickey Rourke, and Brad Dourif and more were in front of the camera, and many of them had mixed feelings about the rocky shooting. Many recall (some endearingly, others contentiously) the rigorous training they were subjected to at “Camp Cimino“. Cast members were woken up early in the morning to attend riding lessons, shooting lessons, dancing lessons, c*ckfighting lessons, roller skating lessons, even Yugoslavian dialect lessons, for hours on end. This level of training may seem excessive, and at times it was, but Cimino wanted to make the perfect film.

Intervention by United Artists

Another issue that contributed to the budget running wild was Cimino’s promotion of friend Joann Carelli. She was an associate producer on The Deer Hunter and a personal friend of Cimino. Despite her inexperience, she was made the producer of Heaven’s Gate, and this inexperience at the helm enabled Cimino to run wild without intervention.

With all the problems, time, and money spent but with little to show, United Artists went against their reputation for respecting the director’s space and decided to fire Carelli. The solution to the problem (as United Artists saw it) was installing someone to oversee the production and help Cimino get back on track. Derek Cavanaugh, who had good intentions (along with Steven Bach and David Field who just wanted to see the film completed), was sent to monitor production and assist Cimino. Of course, this was seen as an attack – the night Cavanaugh was sent to the set, Cimino typed a letter saying Cavanaugh was forbidden to set foot on location as well as the editing room, or even speak to Cimino.

So much damage was exchanged between the director and United Artists that Heaven’s Gate was a production that was falling apart. But Bach and Field crossed their fingers, hoping that Heaven’s Gate would turn out like Apocalypse Now, another film that had a reputation for being a problematic process, but in the end became a hit. Their hopes were that this would be the same case with Heaven’s Gate. But the public would soon catch wind of Cimino’s excessive, money-devouring production, and people started to dismiss a movie that they hadn’t even seen.

Unraveling Begins – Heaven’s Gate Exposed

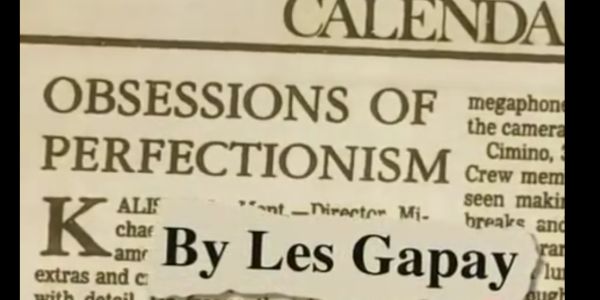

A sly journalist by the name of Les Gapay took a job as an extra to make his way onto the closed set of the film, in order to write an expose of the production. His article illustrated a madhouse led by an egomaniacal director whose spending knew no bounds. Gapay recalls stories of extras fainting, animal cruelty, and all other kinds of indulgences; painting the portrait of a farce that had gone off the rails.

This article fanned the flames of discontent that led to the critical clobbering of Michael Cimino and his larger-than-life picture. Even with all the controversy surrounding the film, Cimino, thanks to a new deal with the studio, got the film in the can. The worst seemed to be over, but post-production proved to be another ordeal.

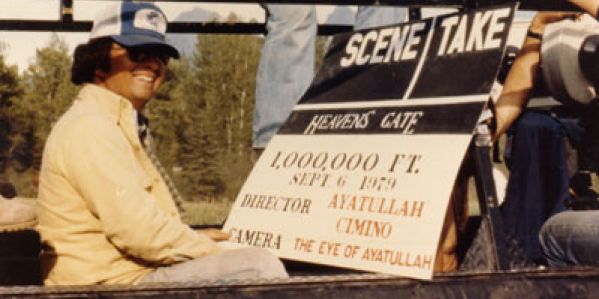

Cimino had shot a record 1.5 million feet of film, with somewhere around 225 hours of footage. Now all that had to be done was to edit the film. Cobbling a movie from 1.5 million feet of film, though, is no easy task.

Final Cut, Post Production, Debut, and Critical Outrage

Having final cut, the director retains the right to execute the film any way he wanted to. The studio asked that the film clock in around three hours, and so after eight months of editing Cimino was ready to show his work print. The film United Artists saw had a running time of five hours and twenty-five minutes, so Cimino had to once again edit it down.

Under pressure to make the Christmas release, the film was cut multiple times under extreme duress. By the time it was ready for its premiere, it was still wet from processing and no one had actually seen the full theatrical cut.

After the premiere, the reviews were out, and the fate of the film was sealed. Critics were merciless in their many scathing reviews. Vincent Canby said the film was like “a four-hour walking tour of one’s own living room.” Other headlines called it an “unqualified disaster.” After a week in theaters, Cimino posted a full page letter in Variety asking that the film be pulled from theaters so that it could be edited with the same care from which the project started. However, this second cut didn’t have a successful run either.

Life, Death, and Resurrection – The Second Life of Heaven’s Gate

After two years and thirty-six million dollars, Heaven’s Gate was known as the biggest box office failure of all time.

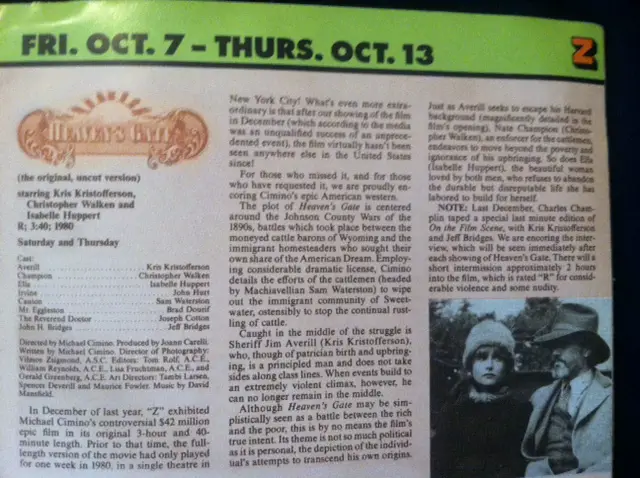

As time had passed after its disastrous premiere, Jerry Harvey, head programmer of the Z Channel (the first paid cable channel) and friend of Cimino aired Heaven’s Gate in its “original running time” of three hours and forty minutes. This effort from the Z Channel gave the film a formidable encore, as it let a ray of positive reception finally touch the film.

The film knocked around on various home video formats, VHS, Laserdisc, and DVD, but the Criterion Collection, with the directors approval, released a supervised restoration of the film on DVD and Blu-Ray. This copy looks and sounds great, and has the same running time that was aired thirty years previous on the Z Channel.

What was known as the biggest flop in the history of cinema has undergone a renaissance exceeding anyone’s expectations, and it has a new following spanning a new generation of cinephiles. Heaven’s Gate is not a perfect film, but it has a lot to offer if you give it a chance. Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography is breathtaking, the sheer scope is unlike any other film, and this cut is the closest we will get to see of the director’s original vision.

Masterpiece, or Travesty?

Although critics hissed at Cimino’s misunderstood epic, it seems as if they judged the production of the film, not the movie itself. It may have been made by an individual who went overboard and proved to be self indulgent, but Heaven’s Gate is an undeniably beautiful and important film.

Still a hot button issue in the movie business, Heaven’s Gate is a perfect analogy if you want to explain the beginning and end of The New Hollywood era. Studios were making overblown productions that no one had any interest in; therefore they gave the directors carte blanche, which lead to an overblown epic production.

Michael Cimino wasn’t the first, nor will he be the last to go over-budget. Regardless, Heaven’s Gate is a unique and ambitious film that should be seen by any curious movie buff.

So what are your thoughts on Heaven’s Gate? Should the production of a movie be a factor of its success, or are filmmakers excused for going over-budget only when a film is successful? Let us know in the comments!

(top image – Heaven’s Gate (1980) source: United Artists)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art, or entertainment; movies of every kind have something to say. And there is something to say about every movie.