Written by experimental filmmakers James N. Kienitz Wilkins and Robin Schavoir, and captured by editor/co-writer Wilkins on a Sony BVW-200 camera equipped with a Betacam SP videotape, this tightly controlled production is consciously low-budget. Employing timeworn technology to give the film an ’80s feel or the bright, fuzzy look of a home video, it intentionally utilizes its cheap appearance to mimic projects from the past, marginally sampling the aesthetic but foregrounding where we should draw our attention too: not barefaced plagiarism per se, but the struggle of the artist and the contrast between authenticity and sophistry. That said, The Plagiarists isn’t so much a start to finish type of film, it’s more of a short-lived anecdote that ravels like a provocative scheme, a frustratingly productive one for that matter.

Director Peter Parlow is seated at the helm, steering this lo-fi indie in a direction that begins with Anna (Lucy Kaminsky) and Tyler (Eamon Monaghan), a garrulous 3-year couple, as they’re on their way to visit their good friend Allison (Emily Davis) until their car breaks down in the middle of a gelid, remote woodland setting. Tyler is a discontented cinematographer who works on commercial shoots but aspires to make his own movie, while Anna is a confounded writer who wants to finish her novel but can’t decide if it’s a memoir or an elaborate piece of fiction. They bicker at each other with persistence and are undecided about their future, but they’re always right.

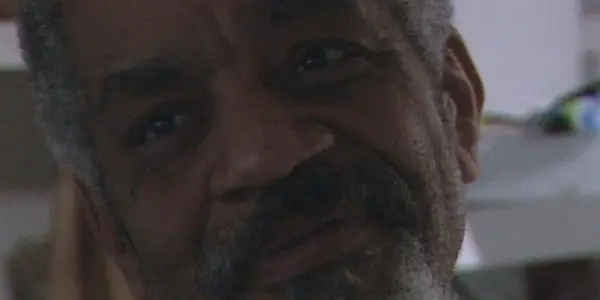

Soon enough, Anna and Tyler are confronted by Clip (William Michael Payne), a fellow passerby who offers them overnight hospitality while they wait for repairs. Knowing their behavior, they furtively confer over whether or not to accept Clip’s assistance. They, a prosperous, car-less white couple, tell themselves their hesitance is not based on the fact that Clip is black, even so, the fact that they even establish their dubiety isn’t determined by Clip’s race is all the more revealing. They ultimately accept Clip’s offer and stay at his house while their car gets repaired. Anna, Tyler and Clip start drinking together, with Anna reflecting on her debilitated writing career, and Tyler reflecting on how he isn’t a true filmmaker because he hasn’t created a film yet. Tyler wanders around, leaving Anna in the kitchen with Clip, who instantly entrances Anna as he communicates a lyrically graceful recollection of his childhood — it’s vivid, emblematic and lifeful, inspiring Anna to continue her writing career.

Next summer, the couple is on their way to visit Allison again. After listening to more unbounded hokum from Tyler, Anna brushes off his inane comments and proceeds on reading a first-person book — without spoiling the novel, it’s written by a European author and his name comes up constantly during the second half. One passage catches her interest, and she’s horrifically surprised by the recent revelation that Clip’s seemingly autobiographical trance was actually a literatim recitation of a central paragraph in the novel. Anna is bemused and repulsed by this latest reveal, utterly confused by Clip’s depraved decision to plagiarize and emote thoughts that were never his to express. This minor lie triggers a discourse between the couple, as well as Allison. Despite the 76-minute runtime, this tiny lie expands further into ambitious territories.

An Alluring Examination On Artistic Enterprise

How does a lettered observer exhume the depths of an artist’s work? By that, I mean how does one tell authenticity from sophism, the possession of originality averse to the artistic application? When we first meet Anna and Tyler, they’re whiny, self-absorbed and emit signs of tacit racism. So that’s probably why Lucy Kaminsky and Eamon Monaghan give stagy performances that in no way encompass how the majority of real-life humans act. They’re whingeing performers, vivid caricatures of artist fatigue and doubt. So it’s also fitting when Clip leads Anna and Tyler into his home, that he looks straight into the camera and casually says, “You’re gonna roll your eyes.” He may have been looking at the little kid who lives in, or is staying at, Clip’s house, but he was also talking straight to us, somehow warning us of Anna and Tyler’s petulance. William Michael Payne’s performance as Clip is fascinatingly forceful and flinty, carrying an aura of mystery with him.

Beneath Anna’s outer mien of self-doubt, lies a vile anxiety Anna endures which potentially stems from racist overtones. When the truth of Clip’s elegant monologue is unveiled, Anna pretty much validates her racist perception: Does she, a white woman, feel that Clip, as an African American, isn’t permitted to the similar perspicacities as a venerated European author? At first, the film plays on Tyler’s sexual anxiety about Clip’s intent and whether or not he’s trying to make a move on Anna. When Tyler and Anna wake up to a woman moaning a couple of rooms down, Tyler at first assumes it’s Anna. Flash-forward to next summer, Anna is wrestling with Clip’s blatant act of plagiarism, and Tyler provides his stance. Being a yay-sayer of conspiracies and left-field concepts, Tyler believes that misrepresenting oneself to beguile or inspire a person is the equivalent of raping them. And because Tyler believes Clip tried to seduce Anna with his fabricated speech, Clip has, in some sense, raped Anna.

As the couple’s wrangle about Clip’s plagiarism continues, polarizing opinions merge into a blurred, undecided hypothesis: Anna feels betrayed, Tyler feels like Clip (metaphorically) raped Anna, and Allison doesn’t see Clip’s plagiarism as a big deal. There’s no clear-cut answer to Clip’s awfully punctilious rendition, even so, Clip’s choice to brazenly mention this sensory passage opens the conversation of an artist imitating previous artists for the sake of a paycheck or literary gratification. Originality is scarce, imitation is frequent. Whether it be a magniloquent author or a filmmaker that harnesses visual imagery to convey their vision, an artist’s creative expression could very well be a slight replica, but with a broader, more signal configuration. After all, an artist needs a paycheck in order to remain an artist, and familiarity is something an artist, a critic and a viewer or reader must contend with. There are different methods to go about to sample from another artist or piece of art, but it depends on how the new artist tinkers with it that measures their vision’s value (hence why we need literary and film critics).

An Odd Experience That Thrives On Ambiguity

The Plagiarists inherits a scattered narrative structure. The first third (titled “Winter”) highlights Anna and Tyler as they meet the enigmatic Clip, which is a mystery in itself. The first act persuades you that The Plagiarists might very well be a sardonic tale of a white couple having their bubble of soundness hampered by the inscrutable presence of Clip, whose intentions are hazy. Clip is seemingly an acquaintance of their friend Allison, yet that doesn’t stop Anna from contacting Allison to ensure their safety. More noticeably, Clip’s connection to the young boy is left unsaid, and Clip has an entire room of vintage camera equipment (including a Sony BVW-200 camera, which is the same camera used to shoot the actual film). It’s a nod to how the movie is shot, and Parlow emphasizes this in one scene where Tyler is actually the one filming the scene before stumbling and dropping the camera, and the screen turns to black. With its disorienting depiction of vacillating, vertiginous close-up/medium shots, the movie’s behavior isn’t meant to be pretty; it’s raw, irritating and outdated, but weirdly necessary in terms of what the film says about sampling. Also, in an interesting option, Clip is never seen in the same frame with Anna and Tyler, pressing the question if Parlow had the trio shoot on different days.

The second act (captioned “Summer”) underscores Clip’s overt plagiarism, all the while making us weather the off-putting dialogue from Tyler, who publicly indicates his offbeat comments of sex slavery and 9/11 in the car and Anna is just trying to read her book, and we’re just trying to understand what this has to do with anything. Strangely, I find merit in the film’s ambiguity. During this act, Anna’s realization that Clip lied to her doesn’t seem to hold dire plot weight, yet that’s the decisive thread that unravels the content of this story until it abruptly detaches and subverts expectations. You would think Anna and Clip would cross paths again and have a heated argument about Clip’s flagrant gesture to stimulate with inventive, distinguished detail, but that’s merely a memory resurfacing in Anna’s mind. The divulgence of Clip’s lie disgustingly vindicates Anna’s sordid outlook on what makes a noble writer, and apparently, to her, that kind of ingenious wording from Clip was “uncharacteristic” of him. In the process of comprehending this disclosure, Anna continues to dig herself into a hole she can’t get out of.

The third act (captioned “Winter”, but instead of going chronologically, this act is a prequel to the first act and first “Winter”) is a succession of brumal images accompanied by a voice-over letter written by Allison to Anna, talking about the significance of the written word compared to the stature of the moving image. This concluding section disengages with Anna and Tyler, getting the final word that just so happens to be cited words from a Guardian article. Instead of concealing this plagiarism, Parlow’s movie credits paragraphs from the renowned European author; from NPR’s radio show in which critic Justin Chang discusses Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here; and, of course, from a Guardian article about books and movies. So in many ways, The Plagiarists relies on sources, but it still creates an experimental project that doesn’t shamelessly borrow without plowing its own route.

The Plagiarists Is One Of The Year’s Most Spellbinding Indies

Peter Parlow’s The Plagiarists offers tempting philosophical and theoretical thought regarding artistic ingenuity. It’s understandable how someone could be incredibly annoyed by the film and the sheer uncertainty of what the filmmaker wants to say. The non sequitur dialogue throws you off: At one point, Tyler complains about Anna and Allison wanting lattes instead of hot coffee, the deception of sex slavery, and Tyler deviates from the topic of filmmaking to Justin Bieber. Still, this is one captivating exercise of subterfuge. It doesn’t focus deeply on the characters or the setting as much as it calls attention to its digressive prose and hard-edged visual aesthetic.

The Plagiarists is peculiar, fairly self-reflexive, and laced with grueling yet equally as rewarding ambiguity that comes from the artists’ seat. An artist wants to create stories, entrance audiences, sustain relevance or radiate deep-seated importance, and sometimes it feels like originality is fused with an omnipotent quality, something most artists may never wholly attain, but a modest reproduction may very well be just as effective. The Plagiarists will sneak up on you, even if you dare to renounce it.

Have you seen The Plagiarists? After reading our review, do you have any interest in seeing it? Let us know in the comments!

The Plagiarists made its premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival on February 8, 2019. It received a limited U.S. theatrical release on June 28, 2019.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.