NYFF 2020: THE MONOPOLY OF VIOLENCE

Stephanie Archer is 39 year old film fanatic living in…

The balance of power and the legitimacy of violence has been shifting for some time throughout the world and the challenge of defining illegal force has been building, growing into a cry for change. As citizens of a state, country, or republic, we give the power to the institution, yet we have no power to take it away. So who has the legitimacy to say what is acceptable? And who will win the fight for it?

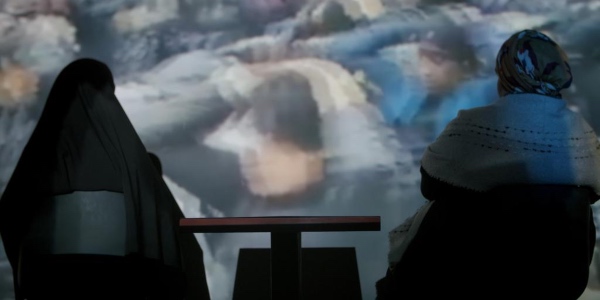

The Monopoly of Violence, from director David Dufresne, tackles the idea of legitimacy with regards to the violence imposed by one’s government, utilizing talking heads from both sides of the issue. It’s a unique approach by the filmmakers to not only have viewpoints from both sides but to have them comment on the same footage we are viewing, and not just discussing but seemingly watching along. As they try to understand the violence they have witnessed, and even become victims of, the question at hand seems to have clear definitions while losing clarity all the same.

Defining Legitimacy

Over the course of its 90-minute run, The Monopoly of Violence introduces three types of violence that are witnessed and debated within the film. The first is institutional violence – the “state’s right”. This form of violence gives life to revolutionary violence, which could abolish the first. Yet, if the power balance leans to heavily towards the institution, we arrive at repressive violence which will stifle the revolutionary as it is an accomplice to the first. It is a back and forth battle between what can be deemed legitimate and what is. As the tides change, so does the explanation. We are all fighting with the mythology of the republic.

The state is given the power by the people to maintain public order. Because of this, the force used is deemed legitimate. This cycle of violence begins the moment you begin to question whether the state is in fact protecting you. And if they are no longer protecting us, do they still have the right to be violent? This is why defining, examining, and redefining legitimacy is so important, boasting the vital importance for films like The Monopoly of Violence – they keep the conversation going.

For this film, there is a deep examination, one the state seems to deny to its citizens, into the violence and question of legitimacy when it comes to the demonstrations in France – though many will find its examination far from limited, rhetoric, behaviors, and support mirroring and transcending borders. From its beginning, there is a nervousness of the talking heads as they prepare to share their stories and defend their perspectives. The Monopoly of Violence appears to not hold a bias, allowing talking heads from both sides of the argument to discuss not only with the camera but with each other. While the film does lean more in one direction, it does not affect the attempt of unbiased perspective in the film. A large part is rather derived from the eyes of the beholder and the side of the discussion they themselves hold.

One of the things the film could have done was to slow down. It is a rapid-fire of imagery and conversation. While many viewers will find the pace of the footage appropriate, the conversation flies by faster than can be comprehended in the time allotted – especially as the reading of subtitles will be necessary for many. There is also little context given to the demonstrations you are seeing, the references by the talking heads filling in the gaps. There are also no title cards to introduce each person speaking and contributing to the documentary. We are left to match them to the videos, in some cases the victims, subsequently only presenting each as a member of one side or the other of the argument.

It is hard as a viewer not to find comparisons to home, or to other places around the world. The rhetoric of the police and their supporters is terrifyingly familiar: “if you are wearing a vest, we are not on the same side”, “They insulted the cop”, and they felt “picked on”. I myself felt I was doing the film both a disservice and an honor finding the comparisons, its relevancy proving the importance of a documentary of this nature – yet, at the expense of thinking of my own country and its citizens. You don’t want to take anything away from the plight of the citizens of France, but it is hard not to begin seeing this as a globalized problem of humanity.

And while you find the similarities, it is gut-wrenching when you hear that the police and France are encouraged to bring this violence down on their citizens. As one talking head admits, it is the most violent cops in France that are given the medals and the honor. And they are backed by supporters who retain the state’s legitimacy to encourage this behavior. The police supporters are rigid, deferring to quotes frequently, unaware and unaffected by the demonstrators, their supporters, and the victims, who are more emotional – and rightly so. It is in these moments, outside of the footage The Monopoly of Violence shows the deepest pain, the stress, the fear, and the need for change. Where one is rigid, the other appears to be mailable and open for constructive conversation – for change.

One of the most interesting aspects of The Monopoly of Violence was not the film’s use of actual demonstration footage but also including footage of the same locations after the violence has ended. There is a calmness to seeing it back as the way it always was, peaceful. Yet there is a terror in the showcase of its tranquility, almost no evidence of the violence this one locale was witness to – as though it never happened. Legitimacy retained and revolution repressed.

Changing the Narrative

The introduction of technology has added to the pivotal change in the legitimacy of violence. No longer are citizens reading of the violence, dependent on the printed words or those spoken by their leaders. The perspective and narrative can no longer be controlled. We are no longer limited to one side. Technology opens the door for all to step in and provide scrutiny and cast judgment on what they have witnessed. With the invention of the smartphone, portable and compact, it instantly unites those around a country and the world, allowing all who view it a chance to be apart of what it happing, in live time. This in itself creates violence.

More fight back against the violence they are now seeing, many for the first time, social media and news outlets expanding the reach. But it also creates violence from those who are now losing control. Perceptions are altered as what could be the cause and the trigger for legitimate violence. Could a demonstrator recording a police office incur violence? Should it? And in the same regard, could the power of instant outreach insight violence in those who otherwise would have been unaware in the past?

Conclusion: The Monopoly of Violence

I had reviewed a film earlier this year where I was first introduced to the potential violence brewing in France, unaware that it had already begun to boil over. Viral: Antisemitism in Four Mutations brought both the fear and treatment refugees receive from citizens – they are offered the welfare and housing that the French citizens in poverty are now denied. You saw the conflict and were given an opportunity to understand the fear and anger of the citizens, but also the plight of the refugee. Yet, you were lead to believe that there was a storm brewing, not one that was already occurring amongst its citizens to this extent. So much so, organizations outside of the country (i.e The United Nations) have begun to investigate the government’s handling of violence against its citizens.

Yet, while The Monopoly of Violence will feel completely sympathetic to the demonstrators, there is an empathy the filmmakers give to the police including a broad spectrum of viewers, one talking head speaking of how the police are sacrificed by politicians. Their names, their professions put in the frontlines. They are the pawns in a chess game, and the first to make the move. They are the images we can get behind to blame for the violence, attack/ fight back, and become the face of hate. And while some are far more deserving of this empathy, watching the footage in this documentary not only had me examining the turmoil here in the United States, but had me understanding how many are willing to take this role on. The willingness of the pawn to protect the king – and the institution.

In a world that seems to be leaning more to authoritarian power and rule, we need documentaries such as The Monopoly of Violence to become witnesses to the change and speak up before it is too late. We can be silent and complacent no longer. We need to constantly question and analyze the legitimacy and the government we place our lives and trust in. Because if we don’t, we have as much of a hand in the violence as those we decry.

Watch The Monopoly of Violence

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.