The Mind On Film: Representative or Farfetched?

Rachael Sampson is a Yorkshire screenwriter and film critic. She…

The subject of mental illness and disorders are interesting, educational, and sometimes sensitive topics in film. From watching movies like Girl, Interrupted, The Road Within and The Machinist, audiences learn a great deal about very real and problematic issues surrounding sufferers, however, can it be said that these representations are portrayed correctly? The film industry is guilty of depicting disorders such as hysteria as an illness that only women suffer from, and autism is far too often painted as a superpower, not to mention the unclear representation of schizophrenia, which causes audiences to confuse the illness with dissociative identity disorder.

Obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, borderline personality disorder etc. all have dubious stereotypes surrounding them, and it could be argued that film is responsible for these myths. To those who do not suffer/know someone with mental health issues, cinema might be their only source of knowledge regarding the matter. With a repetition of stereotypes, can it be said that these issues are ill perceived, creating slight derision out of very sensitive and personal matters?

Not So Shameful

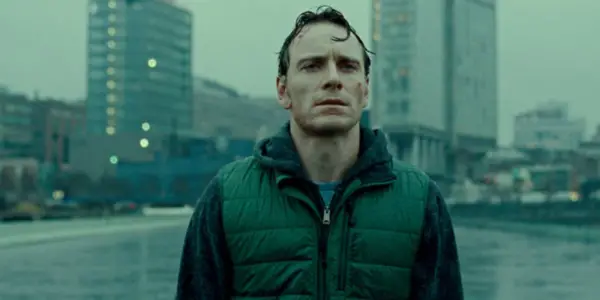

Steve McQueen’s 2011 movie Shame starring Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan is one of the many great examples of accurately manifesting the fragility of mental illness, as it executes the issue at heart with great truth and empathy. Exploring themes of sex addiction, alcoholism, borderline personality disorder, depression and suicide, McQueen’s beautifully shot drama reveals the shameful side to the life of a successful business man suffering from sex addiction, whilst living in the city that never sleeps. The film captures a raw, gritty and uncensored look at a taboo topic, one which is very prevalent in society (with nearly 12 million people suffering from sexual addiction in the United States).

It is often typical for characters in film that show symptoms of sex addiction and alcoholism to be played off as confident and arrogant, with the characterisation angled at constructing appealing and comedic roles to entertain audiences. The poster boy for sex and alcohol: James Bond, backs up this argument, especially when exploring alcoholism.As his constant request for a “shaken, not stirred” martini infers he is a “border-line alcoholic” – stated by the actor himself, Daniel Craig. His nonchalant, confident and hubristic attitude around alcohol deduces that living the life of an alcoholic is somewhat admirable.

Although the main genre of James Bond is adventure and does not directly explore addictive issues, it does however reveal one of the continuous archetypes of an alcoholic, and when this image is constantly produced, it paints a false description of a serious illness. More accurate portrayals of alcoholism can be seen in films such as I Smile Back, The Lost Weekend and Leaving Las Vegas, which highlight the darker, less-glamorous truth of the disease.

Crime Fighting Neurological Disorders

Film and television have so much to offer when it comes to understanding the human condition, and when exploring autism, can it be said that the depictions of the disorder are somewhat cartooned? Since the disorder is on a spectrum, meaning no two sufferers will be exactly the same, why is it that on the big screen, most autistic characters tend to be crime-fighting, insanely intelligent heroes or severely handicapped?

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by impaired social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, and restricted and repetitive behaviour. Due to the way those with the disorder uniquely process information, they can often excel in problem solving, however cinematic images of this show radical superhuman abilities. The broad autistic spectrum is not correctly reflected, with only the polar opposite sides often given airtime; What’s Eating Gilbert Grape shows that of the difficult handicap, then The Imitation Game and television series’ such as The Big Bang Theory and Sherlock reveal the heroic problem solver.

The Imitation Game is based on the life of the code-breaker Alan Turing, however it has been said that Morten Tyldum’s factual film inaccurately portrays the cryptanalyst, as he did not have autism. Sources say that Turing was a much more socially capable person, it is only retrospectively that he has been suspected of having Asperger’s syndrome (which is an autistic condition). The filmmakers seem to have assumed that Turing had autism due to his extraordinary abilities, therefore inaccurately portraying a historical figure through the misconceptions previously set out in typecasting this mental condition.

The issue with representing autism as an arduous handicap or a near power is that neither hold account for the diverse and vast spectrum. Instead of looking for direct portraits of autism, maybe

“we are to cast a wider net and look for the works of art that indirectly index that condition – perhaps even by accident?” – (Todd Kimball Mack on Autism and the Astonishing X-Men)

Examples of this can be seen in Mad Max: Fury Road, as The Dag fits the autistic criteria, through her repetitive behaviour and the way she communicates with others, however it is not strongly forced onto the audience, making it a possibility and not an obvious characteristic. The character of Cyclops (Scott Summers) in X-Men also holds similar connotations as he is not charged with autism being his mutation in this superhero movie. However, one could infer from his ability to shoot light beams from his eyes, that he holds a parallel with the disorder; through his inability to make eye contact with people.

Depression Is Not An Aspiration

Consider the first season of American Horror Story, audiences are introduced to Tate Langdon; a depressed teenager, serial killer and rapist. From that description you would think he was the antagonist of the story, but no. The creators Brad Falchuk and Ryan Murphy angle the light on him in a sympathetic way. Whilst partaking in unspeakable crimes, he is rendered in a Kurt Cobain fashion; a cool kid who hates the world.

This type of representation has been seen many times before, for example in Donnie Darko, the protagonist Donnie is considered admirable and relatable through his teenage angst, however the character is suffering from a major depressive disorder amongst a variety of other mental illnesses.

Donnie meets a girl named Gretchen, and due to their similar, obscure outlook on life, (and both being sufferers of depression thus finding each other relatable) they form a relationship. It is feasible to see this strange love story as endearing, even though both characters mental states rapidly decline. Depression is the foundation of their bond, and the ending concludes comparably to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (however with a more complex storyline).

As Gretchen is the one Donnie wants to be around due to their similar attitudes, it renders the illness as commendable for it unifies them in a positive way. The film depicts the depressed characters in a unique, quirky manner, one that cannot help but be enjoyed, therefore delineating depression as if it is a cool and eccentric aspiration. (This is similar to the unification of Pat’s bipolar disorder and Tiffany’s assumed depression in David O. Russell’s Silver Linings Playbook, another questionable presentation of a mental illness.) As Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is classed as a 15 by the BBFC, it is plausible to suggest that easily influenced teens might look up to these troubled characters and see depression as a desire, for they may idolise alternative and unconventional relationships built on a mental illness.

Other works that similarly show depression as an alluring or an unorthodox quirk include Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides and Sucker Punch. Zack Snyder’s Sucker Punch is an exemplary film when it comes to modelling poor imitations of mental health issues, as the movie dresses the illness’ of the characters in very little – literally, the issue is secondary as the show is stolen by short skirts and a male gaze, side tracking the main issue for sexual gratification. Luckily not all depression is ill-portrayed, movies and television series such as Cake, My Mad Fat Diary, The Skeleton Twins, About A Boy and The Perks of Being a Wallflower manage to restore faith in accurate renditions of the difficulty of tackling and dealing with such a troublesome and common health problem.

Conclusion

Mental health clichés are clearly still being emitted on television and on the big screen, however these stereotypes are dying out. Many writers and directors have been creating more diverse and clear representations of mental illness and the human condition over the last ten years.

This decade has brought audiences some outstanding and eye opening exploits of mental illness’ and disorders many people might not have been aware of or even considered, for example: Still Alice tells the tale of a middle aged woman suffering with the cognitive disorder of dementia, (breaking down the common misconception that only the elderly suffer from the disease). While Lena Dunham’s character in the series Girls paints a bona fide portrait of someone who suffers with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Taboo issues have recently been given the spotlight, allowing society to understand what it is like to suffer with an illness that is not necessarily visually recognisable, from mental disorders such as OCD and schizophrenia to anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. The industry has grown a backbone in depicting perceptions of disorders that are sensitive and overlooked, which in consequence breaks down the inaccurate archetypes. It cannot be ignored that humans are incredibly intricate and diverse creatures, therefore cinema should correlate that aspect and educate audiences on the varied complexities of humankind.

Other notable works that are accurately educating audiences on mental disorders: Welcome To Me and The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (borderline personality disorder), The Drop and Dear John (autism), Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Notebook (dementia), Room and Macbeth (post-traumatic stress disorder), Winter’s Bone and Little Miss Sunshine (depression), Girl, Interrupted and Silver Linings Playbook (OCD).

Which film/television series do you think accurately or inaccurately portray mental illness or disorders? Share your thoughts and comments!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Rachael Sampson is a Yorkshire screenwriter and film critic. She often finds herself daydreaming about Andrea Arnold's filmography or crying over The Graduate.