THE HOLE: Looking for Connection in Isolation

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

In 1998, French company Haut et Court initiated a film project dubbed 2000, Seen By…, in which the impending turn of the millennium was depicted by ten different filmmakers from around the world. One of these filmmakers was Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming-liang, and the resulting film, The Hole, has just been re-released via virtual cinemas in the United States. And there’s no better time to watch it, for The Hole’s apocalyptic rendition of the year 2000 actually bears an eerie resemblance to what the world has been going through in 2020.

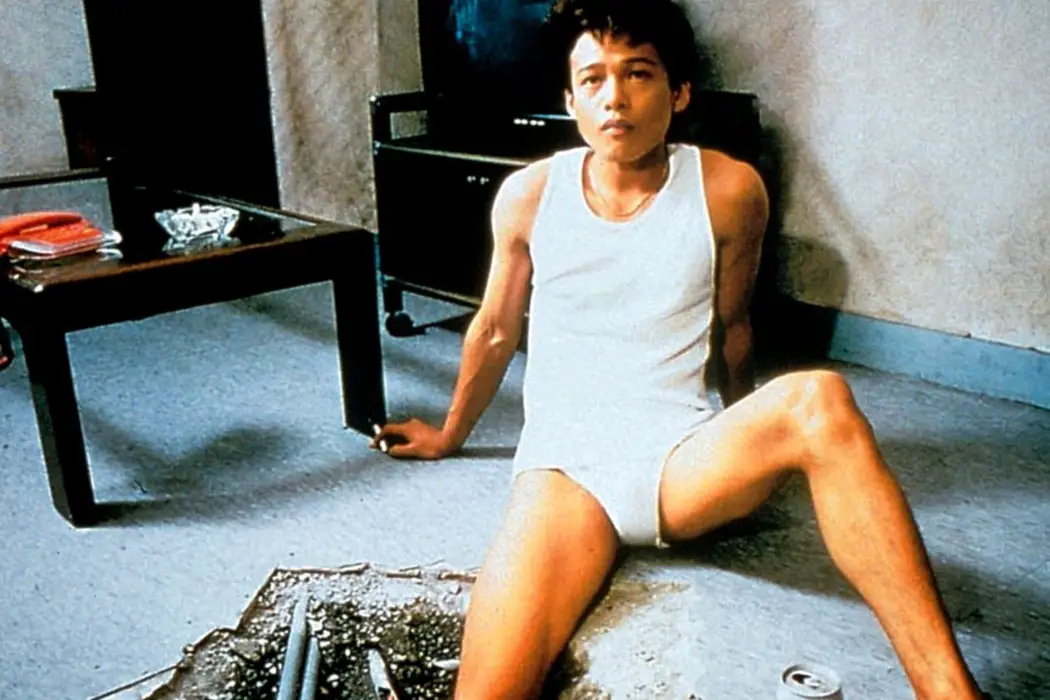

Tsai’s fourth feature, which stars his frequent collaborators Lee Kang-sheng and Yang Kuei-mei, chronicles the slow, lonely days of the residents of a rundown apartment building who refuse to evacuate despite an ongoing pandemic that causes human beings to behave like c*ckroaches. The Hole’s melancholic depiction of the seemingly endless isolation of quarantine, which is occasionally broken up by glittering musical numbers set amidst the grime and rubble of the increasingly dilapidated building, resonates now more than ever as we continue to struggle with the new normal created by the coronavirus pandemic and the hunger for human connection that comes with it.

These Pandemic Times

As the new millennium looms on the horizon, a strange disease has ravaged Taiwan; those who come down with the illness experience flu-like symptoms as well as the disturbing compulsion to crawl around and skitter into dark corners like a c*ckroach. (In an uncomfortable echo of how certain world leaders have chosen to describe the coronavirus, a news broadcast overheard in the film notes that internationally the virus has become known as the “Taiwan virus.”) Despite orders to evacuate and the threat of the water in their area being cut off as soon as the clock strikes midnight on January 1, 2000, a few individuals remain behind and maintain a strange, solitary existence in the quarantine zone.

One of these is a woman (Yang) who spends her days hoarding toilet paper in her increasingly flooded apartment. Indeed, the sound of pouring rain is an almost oppressive constant, with people hoarding the rainwater in buckets to prepare for the inevitable cutting off of the water supply. Frustrated but still unwilling to abandon her apartment, the woman hires a plumber to investigate and fix a leak coming from the apartment of the man upstairs (Lee), an eccentric shop owner with a soft spot for a stray cat that lurks in the area. In checking the pipes, the plumber drills a hole in the floor of the man’s apartment and doesn’t bother to fill it in, leaving a small portal between the two apartments that is at first unwelcome but gradually becomes a source of much-needed interaction between the two neighbors.

Singin’ in the Rain

Despite being annoyed by each other’s behavior on either side of the hole, the man and the woman develop a strange sort of connection, which manifests itself in a series of quirky musical numbers set to cheeky cabaret-style songs sung by Grace Chang that bring flashes of color and sparkle to the monotony of life in the quarantine zone. The striking contrast between the woman’s sequined dresses and glamorous hair and makeup and the increasingly run-down surroundings of the apartment building that is her backdrop makes each musical number a poignant representation of the ongoing struggle to reconcile one’s real-life during a pandemic with the life one dreams of having on the other side of the crisis. The film’s minimal dialogue makes the sound of the rain all the more omnipresent and the musical interludes all the more welcome, a necessary break from the near-silence that threatens to suffocate both the audience and the characters alike.

In the film’s final act, the man upstairs goes so far as to dangle his leg down through the hole in the ceiling, desperate to get the woman’s attention even if it means being the object of her aggravation, and then hammers away at the hole in distress when she doesn’t answer. His past irritation from moments such as when the woman sprayed around a fragrance that wafted up through the hole and annoyed him has now transformed into a dire need to know that she is still there and he is not alone. Needless to say, one can become almost nostalgic for even the most unwelcome of human interactions when one has not spoken with or touched another human being in days, weeks, even months.

If I had watched The Hole pre-coronavirus, I would have still appreciated it as a beautiful, oddball little film, but watching it during the worst pandemic of my lifetime made each emotional beat hit harder than I could have imagined. The apocalypse as depicted onscreen has never looked or felt so eerily familiar as it does here; that the film was originally shot on 16mm only adds to the unlikely sense of intimacy one feels with its characters, as though one is watching a home movie. Tsai is a filmmaker whose extraordinary vision is obvious across the eleven feature films that comprise his oeuvre (all of which star Lee), but even he could not have predicted how much his film would resonate today. Every little detail, from the flickering lights in the apartment building elevator, as the woman performs an incongruously cheerful song about calypso to the local news broadcast advising viewers on the best way to turn instant noodles into a more satisfying meal, helps to create a world that feels more real than it ever should have, one that is claustrophobic and creepy yet not without occasional moments of sheer joy.

Conclusion

With its flashes of humor and music, The Hole is a disturbingly timely depiction of humanity in crisis as well as a reminder that there are always places to find light if you squint hard enough through the gloom.

What do you think? Are you familiar with the films of Tsai Ming-liang? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

The Hole is currently available to stream via virtual cinemas.

Watch The Hole

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.