THE CONVERSATION: Coppola’s Eavesdropping Thriller Still Full of Bravura at 50

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies…

With the forthcoming release of Francis Ford Coppola‘s new film Megalopolis, it makes sense there will be renewed interest in his earlier films. Rialto Pictures is distributing a 4K restoration of The Conversation in honor of the 50th anniversary of its original theatrical release.

Reappraisals of Coppola’s work, particularly something like The Conversation, normally live in the shadow of The Godfather films or Apocalypse Now. It’s far more unassuming in scope. However, the deftness of Coppola comes with how he was able to take all different types of concepts and budgets and make compelling films with the resources at hand.

The premise of The Conversation comes into relief as the opening bird’s eye view slowly descends on a plaza while the title credits play. Coppola’s collaboration with editor and sound designer Walter Murch becomes especially evident as they create a canvas of sound with dialogue and diegetic music spilling into each other. Added to the collage are unnerving electronic frequencies layered in to evoke paranoia and more concretely the art of surveillance.

Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) and his associate Stan (John Cazale) have a two-man operation with a network of associates. It’s like all the movies you’ve ever seen with both men set up in a truck full of equipment and listening devices.

For the uninitiated, it’s easy to question what type of people get into this line of work. Going to conventions, having parties — it feels like they have an office job like anyone else, and in a sense, they do except these men just happen to eavesdrop on people for pay.

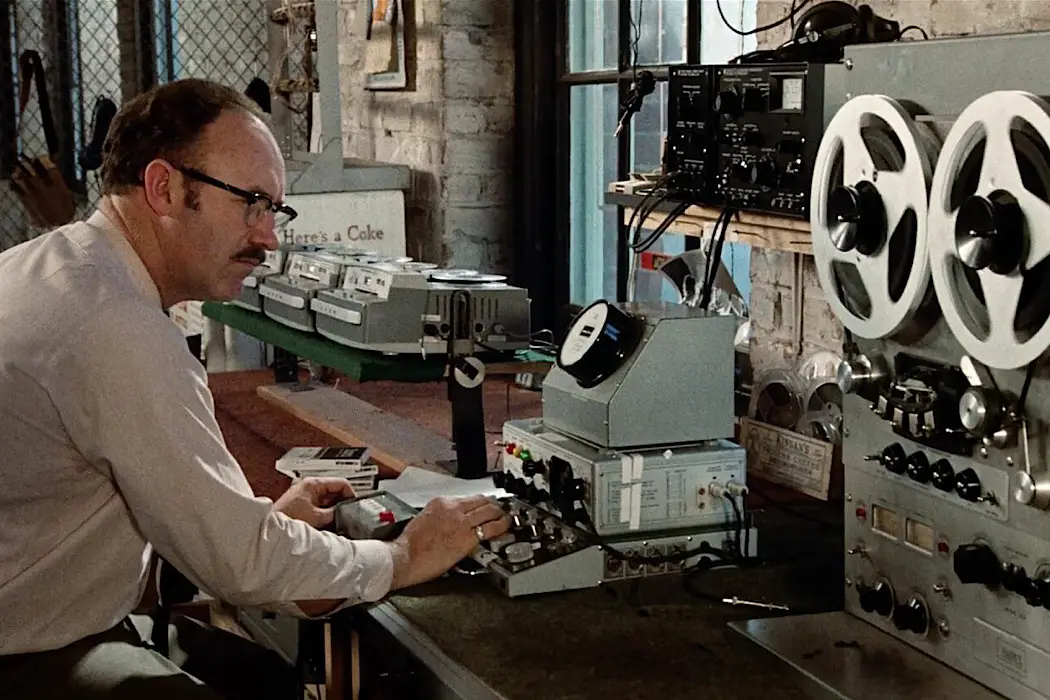

Harry’s place of work is an abandoned warehouse where he listens to recordings over and over again, tinkering with the audio to get the perfect rendering. Stan’s much more open. He wants to know what a man (Frederic Forrest) and a woman (Cindy Williams) were talking about in the courtyard. It’s like a juicy piece of gossip; to us, it feels like a cryptic puzzle with bits of dialogue obscured.

Harry’s clear: “I don’t care what they’re talking about. All I want is a nice, fat recording.” He takes pride in the quality of his work and is not prepared to sit around analyzing the personal problems of his clients; he must remain objective.

This is where they differ because Stan naturally wants to follow his curiosity. It’s human nature. However, this is not what Harry traffics in; you know a man who lives by such a stringent code will come up against something that will break him. Maybe he already has.

The Conversation is one of the great paranoia films of the 1970s in the era of Watergate. The production actually predated the break-in and owed a debt to Michelangelo Antonioni’s earlier film Blow-Up about a photographer who thinks he’s captured a murder on film only for the mystery to disintegrate around him.

David Hemmings‘s hero had a certain hedonistic streak ensconced in the fashion world of Carnaby Street as he was. Part of what makes Gene Hackman‘s portrayal of Harry Caul interesting is his Catholic sense of guilt. Coppola gives him worldly “vices,” but he’s also struggling with what’s deemed good and redeemable in a life that’s purely transactional.

It’s made more pronounced with Caul’s own anonymous personality. He’s an understated man who feels so very unlike Hackman’s persona or at least his more outgoing, mercurial characters. If Harry could, he would keep all his interactions strictly business — he doesn’t want to know or be known by his neighbors — but his stifled conscience allows the slightest emotions to sneak in.

He can’t totally dismiss them, and it makes him such a conflicted individual and a fascinating contradiction even without the conspiracy mounting around him.

The Conversation is less a Watergate-inflected movie and more so a character piece. In this context, any perceived conspiracy almost says less about our institutions on a macroscale and more about human behavior on a microscale. What kind of person allows themselves to be a cog in such an apparatus? The answer to the question might be someone like Harry Caul.

It’s a screenwriting essential that you learn so much about a person from their home life. Harry’s little different. He’s obsessed with locking up, having the only keys to his apartment, and he’s more than a little miffed to find someone’s entered his room without his knowledge; a bottle of spirits and an opened birthday card were left right inside his door. He proceeds to tell his landlady sternly over the phone he’ll have his mail sent to a P.O. box in the future. It informs so much about him.

I also forgot how much of a jazz film The Conversation is. San Francisco was known for some West Coast greats, but the music here effectively plays counterpoint to the sound design. Both the plinking piano score of David Shire and the records Harry listens to with his saxophone in hand.

Harry Caul’s Moral Dilemma

Within the film a snippet of ambiguous dialogue, “He’d kill us if he had the chance,” becomes a kind of lynchpin in the narrative, namely of a moral concern. Because despite his efforts to stay detached, Harry does consider what might happen to this clandestine couple if his client finds out.

It’s easy to forget Robert Duvall is even in the picture. He’s a figurehead projecting authority much like he did later in the darkly satirical Network. Here he’s a cipher.

His assistant, a Mr. Martin Stett (Harrison Ford), is the go-between. In one of their early encounters, The Director (Duvall) is unavailable and Harry’s not prepared to hand over the tapes and take his renumeration until he’s seen him in person. He’s fastidious and decidedly set in the rhythms of his ways.

Over time we recognize more signs of Harry’s moderately devout Catholicism; he goes to confession and asks his colleagues to refrain from taking the Lord’s name in vain. But it remains to be seen where these inclinations come from and if they are little more than behavior modifications. Is he held to a higher spiritual ethic or power?

Later, Harry attends a convention of all your typical surveillance types. If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. An event like this wouldn’t be complete without the free pens and other swag.

One of the booths is manned by an East Coast competitor, Bernie Moran (Allen Garfield), who’s poached the talents of an unsatisfied Stan. He’s a blustering guy oozing with confidence, and he’s done his research on Harry’s body of work. Bernie must be good, but not as good as he thinks. We know the type.

It’s a battle of egos, and Harry takes some small relish in keeping his trade secrets to himself. The fact that his reputation precedes him also seems to please him, though he too suffers the deadly sin of pride. Any time he’s belittled or beaten in his own business, he’s left distraught. For a man who makes a living listening to other people, he can’t bear being listened to.

After the evening crowd dissipates, he spends the wee hours with a blonde named Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae). It’s not his only relationship. Early on he pays a visit to a lady friend (Teri Garr) on his birthday, but he rarely opens up or lets his guard down. For whatever reason, he wants companionship, even the satiation of his carnal urges, without having to be known.

They’re caught between dreams and listless sleep as the warehouse becomes a cavernous velodrome of sound reverberating the fated couple back at him. When he awakes, Harry finds both the girl and his tapes gone. Whether they’re related or not feels immaterial. Everything seems in jeopardy.

There’s this sinking sense Harry is involved in something he does not understand and in this way, it shares a kinship with Chinatown from the same year even if his motivations play in contrast to Jack Nicholson‘s J.J. Gittes. A helplessness sets in.

Conclusion: The Conversation

In the final moments, Harry systematically combs through his apartment until he makes his way to the relic of Mother Mary perched on his shelf. He proceeds to bust it open suspecting a bug is planted inside.

It’s empty but the image speaks volumes. Even the religion he practices cannot save him because it too feels like a kind of self-monitoring legalism. We watch it being sacrificed on the altar before us.

By the end, his place is completely trashed. He’s just a lonely jazz man playing his sax in what looks like a bombed-out apartment. The film camera pans around as if undertaking an act of surveillance. We know he’s being watched and listened to.

I’m not sure what’s more perturbing, the fact that the walls have ears, or here is this dismal man all alone in the world wailing away on his saxophone. It’s a stark portrait where our general anxieties cannot be fully extricated from the darkness of the human heart.

Perhaps Caul isn’t as corrupt as Michael Corleone or as deranged as Colonel Kurtz, and yet his drab, little life is just as miserable if not more so for how empty and unextraordinary it feels.

The Conversation is being rereleased in select theaters in the U.S. starting August 9th, 2024

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies with him. Follow his frequent musings at Film Inquiry and on his blog 4 Star Films. Soli Deo Gloria.