THE BOLSHEVIK TRILOGY: Resistance Is Not Futile, But Necessary

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

In the essay by film historian Amy Sargeant that accompanies Flicker Alley’s pristine new release of three films by Vsevolod Pudovkin dubbed The Bolshevik Trilogy, Sargeant cites a quote by Pudovkin that well summarizes the great Soviet filmmaker’s use of montage: “To show something as everyone sees it is to have accomplished nothing.” Pudovkin explains this concept further in his book Film Technique and Film Acting:

“To show something as everyone sees it is to have accomplished nothing. Not that material that is embraced in a first, casual, merely general and superficial glance is required, but that which discloses itself to an intent and searching glance, that can and will see deeper. This is the reason why the greatest artists, those technicians who feel the film most acutely, deepen their work with details.”

What Pudovkin is saying is that great filmmaking does not simply portray an event as it is happening from one perspective; while realistic, it is also simplistic and does not invite the viewer to look beyond the surface of what is happening. Rather, great filmmaking invites the viewer to look deeper into what is happening on the screen by juxtaposing multiple perspectives of an event, close-ups and wide shots, literal actions as well as the symbolic, and editing all of these together to create something far more complex and meaningful. That is what elevates filmmaking to the level of art.

The three films by Pudovkin that are included in this set – Mother, The End of St. Petersburg, and Storm Over Asia – all illustrate this theory brilliantly. While his work might not be as universally well-known by casual film fans as that of his contemporary Sergei Eisenstein, Pudovkin’s three early revolutionary works can teach us just as much about the art of filmmaking – not to mention, the importance of rebellion.

Family Drama

Released in 1926, Mother was Pudovkin’s first feature-length film and, in my opinion, the strongest one in The Bolshevik Trilogy. Unlike the films of Eisenstein, which focused on the actions of the masses in events like the 1905 Black Sea Fleet mutinies (Battleship Potemkin) and the 1917 October Revolution (October), Pudovkin’s films tend to zero in on individuals taking part in these and other related historic events. This focus on the individual – in particular, the titular character, whose family members end up on opposing sides of a factory strike – is what makes Mother such a powerful narrative.

Mother centers on a family of three: the mother (Vera Baranovskaya) takes care of the home and has little concern for what goes on outside it, the drunken father (Aleksandr Chistyakov) only shows up at home to steal items that he can barter for more alcohol, and the son (Nikolai Batalov) secretly plots a strike with his fellow workers. The factory bigwigs realize that the father can be easily twisted to their purposes and essentially used as a blunt instrument to help crush an impending strike; all they have to do is keep him drowning in drink and he’ll do whatever they say. Needless to say, when father and son recognize each other on either side of the fight, it’s already too late to stop the wheels of tragedy from turning and crushing them underneath.

After riots break out and the father dies in the resulting violence, the mother is willing to do anything to keep her son from being arrested for his involvement – including revealing his hidden stash of guns in an attempt to barter for his life. Instead, the son is sentenced in a sham trial to hard labor in Siberia. It is only then that the mother realizes the cruelty of the imperial government and the importance of her son’s revolutionary activities. Her change of heart leads her to join up with her son’s fellow workers in an attempt to free him and other prisoners from incarceration. The film’s final moments, in which the mother stubbornly lifts the flag of the revolutionaries and marches onward into the path of dozens of imperial horsemen, are as triumphantly and tragically cinematic as anything in modern movies.

Pudovkin builds tension throughout the film’s climax through the rapid, rhythmic juxtaposition of shots ranging from the close-ups of brass knuckles on the hired strikebreakers’ fingers, flexing with the thirst for violence, to the clattering hooves of the imperial soldiers’ horses as they are held in place, impatiently waiting for the signal to charge the protestors. The violence throughout the film is unflinchingly brutal, including a scene in which a worker is set upon by strikebreakers who smash his head repeatedly against the floor until he is dead. But amidst all the chaos, it is the mother to whom Pudovkin and the viewer repeatedly return. Her transformation from passive homebody to assertive revolutionary in light of her son’s arrest shows how one often needs the crisis to come knocking on one’s own door before one can understand the purpose of radicalizing – something that is all too relevant today.

From the City to the Steppes

Released in 1927, The End of St. Petersburg lacks the emotional heft of Mother, though it too chooses to show mass events through the actions of individuals. This time, our protagonist is a peasant boy (Ivan Chuvelev) who arrives in St. Petersburg to find work and finds himself swept up in World War I followed by the 1917 October Revolution.

Again, Pudovkin uses montage to illustrate the cruel inequalities of the time, juxtaposing scenes of battlefield bloodshed with those of the Russian bourgeois in blissful ignorance. The wealthy ruling class is portrayed much in the same way as in Mother: clad in ensembles reminiscent of the Monopoly Man, complete with cigars that they chomp on menacingly while the workers scrounge for potatoes to eat. Low angles on charging figures highlight the forcefulness of their actions and remind one of the sharp graphic imagery on Soviet propaganda posters, with the diagonal lines providing the effect of movement, always forward.

While Pudovkin believed that image was a far more potent method of storytelling than language, the way intertitles are used in The End of St. Petersburg is visually striking in and of itself and only adds to the film’s inherent tension. Lines are repeated numerous times in quick succession, often with the font increasing in size for emphasis, creating a rhythm that echoes the march of the soldiers on the battlefield and the march of the revolutionaries on the Winter Palace. Commissioned to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the revolution, The End of St. Petersburg ends on a far more upbeat note than Mother, but it also makes less of an emotional impact on the viewer, sacrificing the very specific heartbreak of the earlier film in favor of general patriotic fervor.

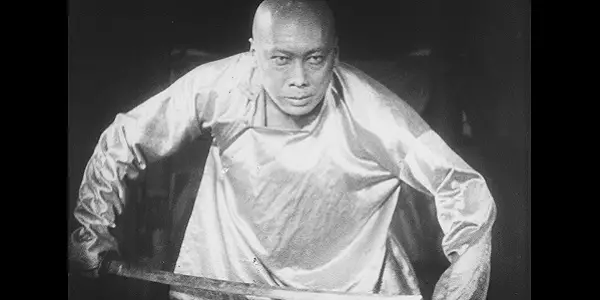

The third film in The Bolshevik Trilogy, Storm Over Asia, carries on the revolutionary themes of its predecessors but moves them to a far different location: Mongolia. Here, our hero (Valéry Inkijinoff) is a Mongolian fur trapper who is cheated out of a valuable fox fur by a trader who bears a striking resemblance to the big bad capitalists of Pudovkin’s earlier films, complete with requisite cigar (though this time he is also clad in a giant fur). Fleeing into the wilderness, the trapper joins the Soviet partisans who are fighting against the occupying British army. While the British never actually occupied Mongolia, it’s easy enough to see these characters as representative of any invading, ruling force led by white men throughout history – so, you know, take your pick.

The army has captured the trapper when they discover an amulet around his neck. In yet another signature use of juxtaposition to create tension, Pudovkin contrasts scenes of the army running around trying to find a translator who can read the note inside the amulet with the impending execution of the trapper on the edge of a cliff. Fortunately, the trapper survives his ordeal, as it is revealed that the amulet signifies that he is a direct descendant of Genghis Khan.

Excited by this discovery, the army plans to exploit his regal heritage and install him as a puppet ruler in Mongolia. However, in the end, the trapper chooses to fight back on behalf of his people rather than rule them, his actions once again showing the importance of individual resistance against oppression even when faced with the most impossible odds. And while Pudovkin’s focus on individuals like the mother and the trapper doesn’t quite jibe with the typical Bolshevik emphasis on the power of the masses, his films resonate with the viewer far more than if they had focused on a sea of indistinguishable faces instead.

Conclusion

Flicker Alley’s new two-disc Blu-ray release of The Bolshevik Trilogy includes a plethora of fascinating extras, including two featurettes focused on Pudovkin’s theories of montage and the short film that marked Pudovkin’s directorial debut, Chess Fever. Overall, it’s a quality set that provides an ample education on the art of film and the act of rebellion.

What do you think? How familiar are you with Soviet cinema? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

The Bolshevik Trilogy was released on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley on March 10, 2020.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.