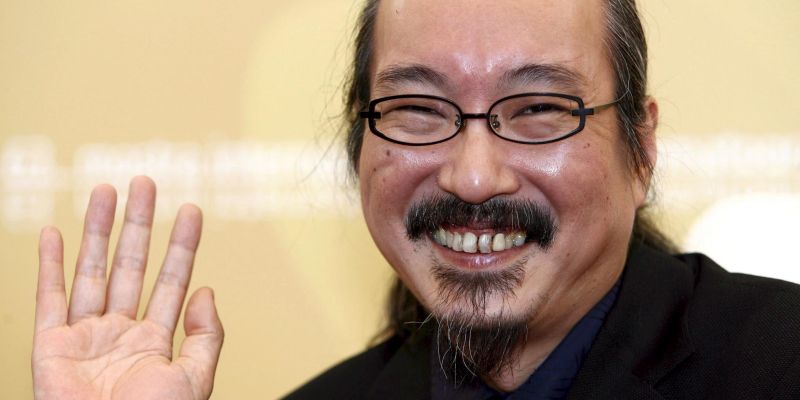

The Beginner’s Guide: Satoshi Kon, Director

Rachel is an MA Film and Screen graduate from Goldsmiths,…

Among the animation giants of Disney and DreamWorks, it’s good to recognize directors who have perfected their craft outside the western sphere, and we’re not talking Hayao Miyazaki here (although he’s but a stone’s throw away).

Satoshi Kon is a Japanese anime director known for his blending of fantasy and reality in his slickly edited films. In contrast to the magical animated realities of Studio Ghibli, Kon’s realities are completely grounded in the modern era, their subject matter rooted in the intertwining of identity and technology. Kon’s influence can be seen outside the realm of animation; nods to his work can be seen in Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream and Christopher Nolan’s Inception.

Over the course of Kon’s life he made four films, all examining dualities, such as: identities on-screen and off screen in the shocking and provocative Perfect Blue, public and private life in the quietly beautiful Millennium Actress, reality and fantasy in comedy Tokyo Godfathers, and the virtual and the real in the hyperactive Paprika. His use of certain filmmaking and animation techniques of transitions, intercutting, and match cutting make his film’s edits feel like liquid. These technical skills and his skillful cinematography have the viewer constantly guessing and reevaluating what they are watching.

Kon died in 2010 at the age of 46 during the creation of his new film Dreaming Machine. He left behind four thoughtful and striking films, along with several manga and one surrealist anime series. He had an unprecedented amount of influence in both animation film and cinema as a medium. In this beginner’s guide to Satoshi Kon, a closer examination and short analysis will be made upon each of this four films, accompanied by a chronological overview of Kon’s career and achievements.

Perfect Blue (1997), Shocking the Industry

Staring off as a manga artist and working his way up in the industry, Kon had worked with many respected industry professionals, including Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) and Katshuiro Otomo (Akira). In 1995, Kon was a scriptwriter, layout artist and art director on the short film Magnetic Rose, that was part of Otomo’s omnibus Memories. It was in this short piece that he first started to develop his blending of reality and fantasy. In 1997, Kon began working on his directorial debut, a film based on Yoshikazu Takeuchi’s novel by the same name, Perfect Blue.

The story is about a girl named Mima, who, after wanting to move on from the sweet voiced J-pop idol lifestyle, leaves her frilly pink music group “CHAM!” to start her career as an actress. Having to prove herself in this new industry, her first role as an actress is in a crime drama called ‘Double Bind’, where she plays a rape victim. After a change in career, her fans become incredibly upset and angry, and they call her a traitor and filthy. With the pressure of her new career, her reputation on the line and a potential stalker, Mima’s psychological state is put into question.

Perfect Blue completely went against the grain of other anime films. It had adult themes and characters and was set in a real world space: contemporary Tokyo. Instead of giant robots and fantastical lands, the film was a psychological, violent thriller for an adult audience. It focused on real-life subjects that reflected issues within Japan’s pop-idol images and online culture. For Kon, Perfect Blue was not focused on the idea of the celebrity but more about a person’s public self and real self, and in Mima’s case, she cannot tell them apart.

The gaps between these identities become non-existent, and this was reflected in Kon’s storytelling style. Due to the budget, the duration of the film had to be cut down. There was no time for a gradual suspense to grow or a fear to develop, and this is where Kon’s fluid editing came in. He experimented with match cuts and intercutting, which saved time in terms of storytelling. It is a technique that he continued to use in all of his films.

Perfect Blue arrived in the West on the back of interest in foreign animation caused by the release of Akira, but the sexual and bloody violence shocked audiences because of its cartoon format. Perfect Blue is by far Kon’s most disturbing film; however many of its themes continued on into his other less-violent movies.

Millennium Actress (2002), The Running Woman

Kon’s wanted his next film to be another adaptation, a novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui called Paprika, but the distribution company went bankrupt, which put the project on the back bench. Kon then started to work on his second film, Millennium Actress.

In Millennium Actress, two filmmakers have tracked down a famous retired movie star named Chiyoko Fujiwara who they wish to interview for a documentary. One of the interviewers, Genya, is a long time fan of Chiyoko and has a key to give her, a personal possession of Chiyoko that she has lost years ago. When she receives the key it helps her talk about her famous career in cinema and also about her personal life. The story interweaves in and out of Chiyoko’s onscreen performances and her personal goal of chasing after a mysterious painter who she has fallen in love with.

Millennium Actress is similar to Perfect Blue is that it deals with the same subject matter of celebrity dualities. Kon’s character Chiyoko shares many similarities with the real-life Japanese actress Setsuko Hara. Her performances in the films of Yoshajiro Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story, made her a legend and a beloved Japanese actress. After being in dozens of films from the ’30s to the ’60s, she retired to a small house and lived in seclusion. Many see the character Chiyoko as the fictitious version of Setsuko.

Distinct from his other films, Millennium Actress is known for pushing the idea of Kon’s seamless editing style, using an optical illusion technique called trompe-l’oeil motif that translates as ‘deceive the eye’. Different from the blurring of realities that confuse Mima in Perfect Blue, the editing here is used to show Chiyoko’s control of her identity as an actress and her real self as she effortlessly travels between them. Chiyoko’s character is known as Kon’s running woman, as she is constantly and literally running from one scene into the next. Combined with Kon’s fluid editing style, her running seems to break time and space. Andrew Osmand (author of Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist) writes: “…running women encapsulate Kon’s animation more than any other image, as flying girls do in Hayao Miyazaki’s anime”.

Tokyo Godfathers (2004), A Christmas Comedy

Straight after Millennium actress, Kon started working on his third film Tokyo Godfathers, a comedy, drama and Christmas film about three homeless people living in Tokyo. Delving into completely new themes and ideas, Kon co-wrote the script with Keiki Nobumoto, who was head scriptwriter for Cowboy Bebop and Wolf’s Rain. Nobumoto made a massive contribution to the script, changing Kon’s style a little, but together they wrote a film that comprised three fully fleshed-out characters, included their histories, personalities and a Christmassy adventure in the space of a 90-minute run-time.

On the night of Christmas Eve, three homeless people find a newborn baby who has been abandoned in a pile of trash. Gin, Hanna and Miyuki (a hopeless drunk, a trans-woman and a teenage runaway, retrospectively) plan to find the baby’s mother and return it to her. As the trio sets out to find leads and follow clues, they bump into people from their pasts and find themselves spiraling into a number of kooky circumstances.

Tokyo Godfathers has quite a straightforward story. Unlike the reality-within-a-reality illusion that Kon normally delves into, the film’s linear narrative is carried by the three main characters. Their personalities all bounce off each other in a simultaneous mutual love and hate for one another. Combined with the narrative device of the Christmas miracle, it’s a spectacularly funny film, which is quite the feat when you are dealing with a serious issue of Tokyo’s growing homeless population.

Also unique to Tokyo Godfathers is Kon’s character Hanna, a trans-homeless woman, who is not only one of the funniest characters in Kon’s films but is treated with immense complexity. Her desired gender is not only used as a comedic trope, but her traumatic past and trans-identity are vital to the film’s themes of family and motherhood. All three of the main characters are complex and each have their own identities that are fundamental to the story and themes of the film, making them the most human and relatable characters out of all of Kon’s films.

Paprika (2006), A Mind-Bending, Time-Altering Finale

In the same year of Tokyo Godfathers, Kon also released a thirteen episode anime called Paranoia Agent. It carried the same themes and atmosphere of Perfect Blue – various characters shred the same issues as Mima, not knowing their fantasies from their realities. The story revolved around a myth of “shounen bat”: members of the public where being assaulted by a mysterious elementary school student equipped with golden skates and a golden bat. After being hit with the baseball bat, problems that the victim had prior to the assault would mysteriously be resolved. The series was a compilation of Kon’s unused story ideas that could easily fit into the show’s format. Then, finally, after years of planning and subsequent cancellations, Kon started working on the adaptation film Paprika.

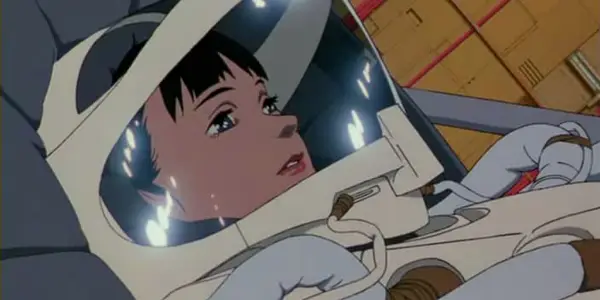

In Paprkia, a new invention of psychotherapy treatment has been created called a DC Mini, which enables psychologists and scientists to have the ability to view people’s dreams. A thief has stolen several DC Minis and is using them to enter people’s minds illegally. A scientist named Chiba, along with her colleagues and a detective, attempt to catch the thief and retrieve the stolen tech along with the help of a hyperactive dream girl named Paprika.

Continuing on the theme of blending realities, Kon this time makes the compassion between reality and dreams. Using the idea of dreams as a suppressed consciousness, the dreams of Paprika are colorful, fantastical and wild. The main heroine, Paprika, is a duality of the scientist Chiba, but instead of battling the counterpart, like Mima and her phantom in Perfect Blue, both women work together as a pair. Chiba is a reserved and analytical scientist, with her counterpart Paprika being the complete opposite; outgoing and untamed. Paprika breezes through scenes, in a similar way that the running girl Chiyoko does in Millennium Actress. She is free of the laws of time and space, jumping into films, billboards, adverts, any image she wants; she has a playful personality like the trio in Tokyo Godfathers.

With all this comparison, it’s easy to see that Paprika embraced everything from Kon’s previous films. It seems, although the thought is a bit gloomy, that this film suits the role of Kon’s last film. Yet it’s generally agreed that even Paprika, with its parade of fun and madness, is not nearly the level of potential that Kon could have reached.

A Post-Modern Man

In May 2010, Satoshi Kon was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given half a year to live. At the time he was working on a new film titled Dreaming Machine; however with not long left he spent it at his home. He composed a final message to his fans that was uploaded to his blog upon his death. He died on August 24 at the age of 46.

Kon‘s craft of animation and understanding of the strengths of the medium excelled his work into new realms. The ideas and themes that his films explore are among the most relevant topics of the modern era. His understanding of identity with technology, screen cultures, the connections between the virtual and the real, memories and dreams – all reflect the time we live in.

Take a weekend to watch Kon‘s four monumental films. Or if that’s too much to ask, his one-minute short film Ohayo (Good Morning) for the Ani*Kuri15 series perfectly captures his work.

Are you familiar with Satoshi Kon‘s animation? What is your favorite work of his?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Rachel is an MA Film and Screen graduate from Goldsmiths, University of London. Her interests lie in cinematic landscapes, interactive media, documentary film and general screen stuffs.