Saying you like Ingmar Bergman is like saying you like cinema. His influence and style have become more than an influence, a defining layer in the foundation of cinema. With some directors you can recall a few classic movies, but with filmmakers like Bergman, who has so many definitive credits as a director, his filmography can almost seem too daunting to follow. The purpose of this Beginner’s Guide is to guide you through Bergman’s epic filmography.

When recalling Bergman’s filmography one has to select the foremost titles from a modicum of classics in order to compile a list of favorite titles. Famous, widely regarded, and well known films like The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Fanny and Alexander, Persona, and Cries and Whispers are frequently referenced, but this handful merely scratches the surface of the master’s inventory.

Early Life: Childhood, Theater, Early Films

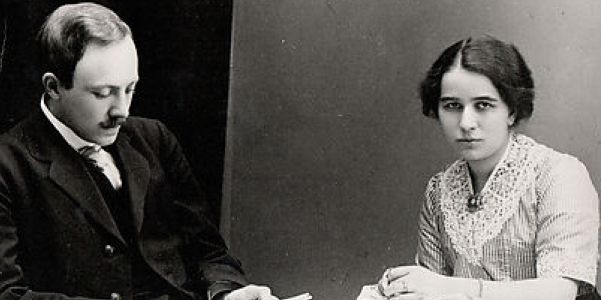

Bergman was born on 14 July 1918 in Uppsala, Sweden. His upbringing was lead by his father autocratic Lutheran Minister Erik Bergman, and his mother Karin Bergman, a nurse and loving subject of one of the director’s few documentaries; Karin’s Face.

Despite recalling occasional moments of warmth Bergman recalls most of his childhood with cold treatment, and harsh punishments from his father. Wetting the bed was an offense that sought the punishment of being locked in dark closets, whippings and most humiliatingly, he would be forced to wear a skirt for the duration of the day. These punishments would be recounted in his later film Fanny and Alexander.

At an early age Bergman sought escape by losing himself in his own imagination and fantasies. His father’s abrasive demeanor solidified the young director’s atheism as he recounts that he lost his faith by the age of eight.

The Magic Lantern

In a cruel turn of fate Bergman’s Aunt Anna came by with Christmas gifts, from the bag she presented one for Bergman, and one for his brother Dag. Young Ingmar was sure that he would receive his sought-after cinematograph, instead his brother received the cinematograph and he was burdened with the mocking gift of a teddy bear.

Luckily for Bergman, his brother Dag couldn’t care less about the cinematograph: he favored tin soldiers and “had armies of them” as Bergman recalls. He saw the cinematograph sitting on the shelf and thought “it’s now or never” and woke his brother up, offering to trade Dag his entire collection of tin soldiers for the cherished movie lantern. Young Bergman’s soldiers won the battle.

Making a Home at the Svensk Filmindustri

Although Alf Sjöberg directed the 1942 film Torment, it is considered to be Bergman’s first movie. During production Ingmar would rush to the set in order to whisper notes to the actors between takes. During the filming of Torment, Bergman had shot interiors as an assistant director; these were some of his first professionally filmed sequences. Torment depicted an oppressive Latin teacher and was a subject of controversy. Bergman’s stern upbringing and rebellious tendencies finally had an outlet in the cinema.

After Torment, Bergman asserted himself as a director both on stage and in film. In 1946 Bergman directed his first film Crisis, followed by It Rains on our Love, A Ship Bound for India, Music in Darkness, Port of Call, Prison, Thirst, and To Joy in a three-year period. These early titles vary in quality but at this early point you can see the germinating themes that would be paramount in the director’s subsequent films.

International Acclaim: Summer with Monika, Smiles of a Midsummer Night, Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal

After being humbled by Victor Sjöström, Ingmar Bergman directed three important films in his earlier career, Summer Interlude in 1951, and in 1953 Sawdust and Tinsel, and his first international breakthrough: Summer with Monika. Featuring stock member to be Harriet Anderson in a breakthrough role, Summer with Monika is a stunning tale of young love and caught the attention of audiences worldwide.

If people operate under the impression that Bergman is the arbitrator of gloomy European cinema his other (of multiple) internationally acclaimed film Smiles of a Summer Night would prove even fans of the director’s work wrong. A bawdy canvas that satirizes manner, mores, class, and sex that would inspire musicals and other films including Woody Allen’s A Midsummer Nights Sex Comedy.

Ingmar Bergman garnered international acclaim with his work at this point in time, but his name would ring out with praise in 1957, with two of what many consider his finest work. The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries are the director’s best-known work, and serve as accessible entry points for those curious about his work, as well as recurring titles that are staples in the education of any self-respecting movie buff. Both films carry symbols that are synonymous with classic international cinema to the point of being iconic.

The Seventh Seal ushered in the partnership of Bergman regulars Max von Sydow and Bibi Anderson. While The Seventh Seal brought together new partnerships, Wild Strawberries starred an aging Victor Sjöström, the same man who put the c*cky young director in check in 1945. His performance is an endearing swan song to an illustrious career.

Following these two major classics Bergman continued to make stimulating and personal films that challenged the cinematic form. As time went on the director pointed a more direct eye on themes of spiritualism, love and of course the existence of God and the nature of humanity. 1958 marked the year of another classic from Bergman, The Magician, followed by another vivid period drama The Virgin Spring in 1960. Both films star Max von Sydow and were entries for best foreign language film, the latter won the nomination.

Silence of God Trilogy: Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light and The Silence

In 1961, Bergman decided to film the first in his “Silence of God” trilogy on the remote Swedish island of Fårö. Armed with cast members of his stock company, Max von Sydow, Gunnar Bjornstrand, and Harriet Anderson, and cinematographer Sven Nykvist the shooting of Through a Glass Darkly commenced. The film would be the first of many movies Bergman would shoot on Fårö Island, which also became his home in later years. It also marked another vital change in his career, because his films were now in contemporary settings with themes directed in a more concise manner leaving the period melodrama (for the most part) behind.

Many consider Bergman’s “Silence of God” trilogy to be some of his finest work and the second installment Winter Light is known as one of his more personal efforts. It’s rumored that the director “realized who he really was” when he made the film.

Followed by the equally captivating 1963 movie The Silence, which exchanges the filmmaker’s heavy approach for an ominous atmosphere of oblique visuals. Sven Nykvist’s camera simultaneously captures images of a war-torn landscape while bringing our attention to the characters facial expressions by use of intimate close-ups. The directors fascination of studying facial expressions through the use of close-up photography would be a burgeoning trademark device in these films. Never has spiritual alienation and emotional bleakness looked so beautiful.

At this point in time it seemed like Bergman could do no wrong, and was hailed as one of the most eminent voices in world cinema.

Second Era, Color, Television and Fårö Island: Persona, Hour of the Wolf, The Ritual, The Passion of Anna

Bergman’s second era (mostly) left the settings of his earlier films behind. His apprehensive study of mankind brought his films to the present day, his following movies examining social alienation more so than spiritual, but the style of existential abandonment consistently remain intact for the rest of Bergman’s career.

While his films from the fifties and early sixties vigorously examine spiritual and religious matters, his focus following the mid sixties (most notably in his 1966 film Persona) had shifted from the disintegration of faith to the disintegration of the psyche. He adopted a more personal style of filmmaking, hired smaller casts and an intimate filming style would be his trademark for many of his following films.

With international acclaim following his projects, MGM distributed one of his most challenging and dynamic studies of psychological horror, Persona. Starring Bibi Anderson, and Liv Ulmann, it concerns the philosophical suffering and solitude in contemporary society as an actress whose inability to speak (because of the horrors in the world we assume) lead to a multi-layered and undeniably complex relationship that deconstructs personality, identity and the cinematic form.

Adopting classic horror movie techniques, while retaining a hallucinatory sense of existential dementia, his 1968 film The Hour of the Wolf is dark, witty and occasionally funny. A high point representation of Bergman’s versatility as a creative maverick.

While Ingmar Bergman was tackling different genres he decided to take on his interpretation of the war film with yet another masterpiece: Shame. With a collection of so many classics, Shame seems to be an overlooked entry among Bergman fans. It’s smart, dramatic, and one of the psychological films on war ever made.

Although it may seem like a downgrade, Bergman began making films for television in 1969. His first television film The Ritual (or The Rite) is a compelling treatise on art and censorship. A jarring and incomparable experience that belongs alongside Bergman’s best work.

Bergman’s triumphant return to color photography in The Passion of Anna (known to everyone else in the world as A Passion) thanks to Sven Nykvist’s diffused cinematography and more wonderful performances from Erland Josephson, Liv Ulmann, Max Von Sydow, and Bibi Anderson, The Passion of Anna is one of Bergman’s most effective psychological studies that is less abrasive and underscored than some of his other work. This makes it a masterpiece of slow burning moral disintegration. Adding to the film’s dramatic gravitas, the long-running romance between Bergman and actor Ulmann was coming to a close. Ulmann recounts this film as especially difficult, but the result are undeniably astounding.

Despite the dialogue-heavy nature of his work, Bergman doesn’t favor improvisation, except in a small amount of his later films including the dinner scenes in The Passion of Anna. Cast members who were on camera were given real wine to let the dialog flow freely.

Directorial Missteps: The Serpent’s Egg, The Touch

It would be nice to say that Bergman’s career had no stains but his two films The Touch (1971) and The Serpent’s Egg (1977) are both unanimously regarded as the director’s two failures. Though the films are not without the director’s touch, both suffer from a case of fatal miscasting. Elliot Gould seems to be awkwardly gasping for air in The Touch, while David Carradine stands out like a sore thumb in The Serpent’s Egg, Gould and Carradine, otherwise talented actors, lack the chemistry alongside members of Bergman’s repertory company.

Refining Perfection: Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage

Passionate, provocative and daring in its use of color, the 1972 film Cries and Whispers is a celebrated classic. Nominated for five Oscars and winning one for cinematography (Sven Nykvist) Bergman’s film was one of his most successful titles at home and abroad.

Bergman’s output would slow down in the following years, although this did not result in a decrease in quality. Though the later films in his career would receive theatrical premieres, the bulk of these productions were originally made for television. Bergman’s transport from film to television led to some of his most enthralling work, and is not to be looked at as a reductive career pattern as some of his best work was yet on the way.

After the lavish period drama that was Cries and Whispers, Bergman, armed with a budget of $150,000, an ambitious (and personal) script and a small, dedicated cast took to the filming of his miniseries Scenes from a Marriage. Liv Ulmann and Erland Josephson star as Johan and Marriane, a (seemingly) happily married couple whose lives we learn about in intimate detail almost entirely through the couples conversation and dialogue.

After the lavish period drama that was Cries and Whispers Bergman; armed with a budget of $150,000, an ambitious and personal script paired with a small dedicated cast took to the filming of his miniseries Scenes from a Marriage. Liv Ulmann and Erland Josephson star as Johan and Marriane, a (seemingly) happily married couple whose lives we become immersed in as the narrative progresses. Originally made for Swedish television, the series was edited down into a 167-minute theatrical release.

Tax Charges, Exile and Mozart: The Magic Flute, Face to Face, Autumn Sonata, From the Life of the Marionettes

Breaking the mold of his otherwise woeful oeuvre, Bergman filmed a lively and colorful rendition of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Though made for television, The Magic Flute received a theatrical release and is noted for being the first television movie to have a stereo soundtrack. Although his following film Face to Face released in 1976 was originally another mini-series it seems like the theatrical cut is the only version available to us today. Given the potency of the film, the original television cut is something of a white whale among Bergman fans.

After running into a tax evasion scandal, Ingmar Bergman had personally exiled himself from his native Sweden to Munich, Germany. While in temporary exile Bergman continued to work, and in 1976 he collaborated with Ingrid Bergman in his final film made for a theatrical release, Autumn Sonata. The pairing of actress Ingrid Bergman and Ingmar Bergman proved to be successful and her performance alongside Liv Ulmann is praiseworthy.

While in exile, Bergman’s next film would be an even darker and macabre: From the Life of the Marionettes. The characters, based on supporting characters from Scenes from a Marriage, embark on a path of mental disintegration, adultery, and murder. Like most of Bergman’s work the film is intensely personal, but From the Life of the Marionettes was a dark turn, even from cinema’s forerunner of moody and dark cinema.

Crowning Achievement: Fanny and Alexander

After his self-imposed exile, Bergman came back with his massively successful epic Fanny and Alexander. The theatrical cut was an international hit (including four Academy Awards among its many accolades) but the full-length mini-series is an expansive saga that stands as the directors most towering achievement. Fanny and Alexander (1982) is a rewarding and magnificent study of the Ekhdal family and the turmoil that follows in the death of the titular character’s father. Their fall from grace into an abusive and manipulative stepfather (whose harsh methods of discipline are modeled after Bergman’s real father) their escape and reunion with their family is directed with tactful grace.

Although the theatrical release of Fanny and Alexander was warmly received it wasn’t until the Criterion Collection combined the theatrical cut as well the miniseries in their 2004 DVD set, it has been since updated to Blu-Ray. Although Bergman had announced that Fanny and Alexander would be his final film, the premier director wasn’t going to retire.

After the opulent production of Fanny and Alexander, Bergman returned to the terse and confined personal type of moviemaking with his concise, and palatable TV movie After the Rehearsal. The movie is short and “sweet” but it’s as captivating as anything the director had committed to screen.

The Final Years: Saraband, Bergman Island

By 2003, a 85 year old Bergman made his final film Saraband. Erland Josephson and Liv Ulmann reprise their roles as Johan and Marriane thirty years later after Scenes from a Marriage. Saraband is an appropriate swan song for Bergman’s expansive career as a writer and filmmaker. In 2006 Bergman broke his mold as a recluse and participated in a series of interviews with cultural reporter for Swedish television Marie Nyreröd on the remote island of Fårö where Bergman spent his years living in seclusion.

The interviews were originally aired as three one-hour segments for Swedish television but the 80-minute version Bergman Island got (like many of Bergman’s own films) a Criterion release. Although it received a spine number it is now featured as a special feature on the The Seventh Seal Blu-Ray release.

One year later Bergman would pass away on July 30, 2007, he was 89 years old.

Bergman’s influence is so prevalent we can see references to his work throughout cinema since his films became in vogue in the fifties, so much so the term “Bergmanesque” is a part of our cinematic vernacular. Ingmar Bergman made a modicum of films, though his early work dabbled in genres, Bergman’s own cathartic brand of self-reflective cinema paved a new path in the world of film that is consistently referential yet impossible to imitate. Bergman’s peerless work studied the harsh realities of the human spirit, the daunting nature of faith and the frequently destructive elements of love.

Ingmar Bergman wasn’t just a filmmaker but the forerunner for elevating the level or artistry in cinema, as well as one of the great artists of the 20th Century.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.