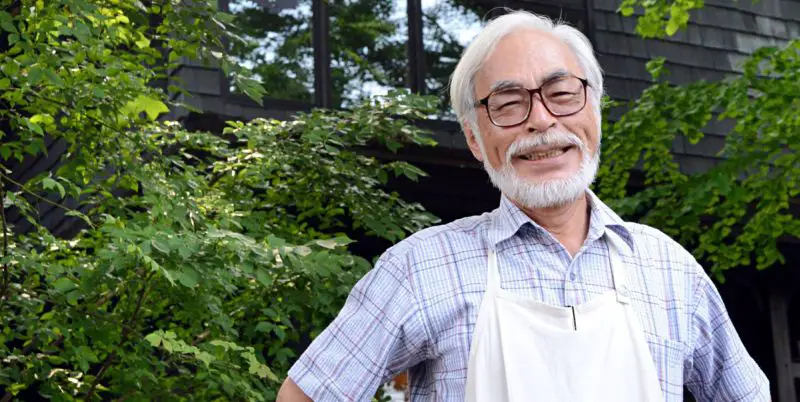

The Beginner’s Guide: Hayao Miyazaki, Director

Alexandre Thiebaut is a part time writter, a full time…

How to summarise Hayao Miyazaki in a few words? Brilliant, magical, ecologist, fantastic, cultural, wise, a true master of his art: animation. The Japanese director is one of the most iconic and undisputed great film directors of our times. Over a career than spanned five decades, Miyazaki has vowed to enchant, mesmerise and enlighten the viewers willing to delve into the master’s lyrical worlds.

From his first major hit Nausicaä in 1984, Miyazaki has been extraordinarily consistent in the quality, the richness and the freshness of his following features, building one of the most accomplished filmography in cinema’s history made of strong testament films to educate the world and its people (Nausicaä, Mononoke, The Wind Rises), delightful stories (Kiki, Ponyo, Totoro) and beautiful adventures (Laputa, Howl’s Castle, Spirited Away, Porco Rosso).

In this beginner’s guide of Hayao Miazaki we will browse through the Japanese director’s most important works outlining his style, the themes dear to him and the brushes of magic he graced the Seventh Art with.

Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind (1984)

Nausicaä is the first major work of Miyazaki and perhaps the most important piece of work of the director. After finding its definite drawing style through the intensive study of the French animated film Le Roi et L’oiseau (the King and the Mockingbird) by Paul Grimault in the early 80’s, Miyazaki wrote, drew and directed his second full feature film as if it would be his last. The result is an extremely ambitious movie that first introduced Hayao Miyazaki to the world and opened a new era for animation.

Considered as a cult film, Nausicaä is about an eponymous character, a princess, who strives to save the world as she can from its inherent destruction. We are a thousand years after human-created monsters destroyed the earth, which is now trying to reconstruct itself at the cost of the human civilization. A toxic forest and its enormous insects are the threat, echoing the possible results of a nuclear war that could lead to the extinction of the human race.

With Nausicaä, Miyazaki presented to the world a kind of hero that was never seen or read about before. Carrying the whole film, the princess Nausicaä surprises and forces admiration by her brave decision-making and her ability not to judge an enemy, but rather to try to understand why they act in such a way. Nausicaä flies above the realms of good and evil, all protagonists in the movie act deleteriously, convinced that they are acting for the good and protection of their kind – even the planet itself. The princess Nausicaä alone can lead the way through her peaceful yet active and costly actions, she is a savior deified in the final moments of the movie, a legendary figure who saved Earth and all its inhabitants from killing each other.

With Nausicaä, Miyazaki offers not only a captivating movie, extremely original and innovative for its days, and not only clearly states his position towards war and the preservation of our ecologic system, but offers a solution as how humanity should behave in order to protect life on Earth. With Nausicaä, Miyazaki’s great purpose as an artist became clear: to bewitch and educate to perhaps make the world a better place.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and the years 1986 to 1996

Miyazaki followed his first masterpiece by Conan the Future Boy in the same year, a full length movie based on the TV series Conan, then came another major work in the director’s filmography: Laputa – the Castle in the Sky. It is an epic story dressed in Jules Vernien style, about a secret stone kept by a young princess that holds the mystery of a castle in the sky belonging to a lost civilization – the Atlantis. Miyazaki re-explored some themes already visited in Nausicaä, with the giants created by man that destroyed the world once upon a time, as well as the human race for conquest, survival and domination.

Visually we can see traces of Miyazaki’s evolution towards his landmark microscopic details in the background of a room, a town, a house, a scene. His landscapes and background are so infinite, so precise and typical that they truly give life to its scenery and characters. A few years later the base of Laputa’s scenario would be used and remodeled to give birth to the popular animation TV series Nadia, The Secret of Blue Water, by the studio Gainax.

In 1988 came My Neighbor Totoro, which cemented the director as a cultural icon, and a national treasure. Its main character Totoro, a God of the Forest, has been elected the most beloved animation figure in Japan throughout the years and is still to this day, 27 years later, one of the most represented figures in Japan. You can find it on museum tickets, on handbags, in soft drinks advertisements, et cetera.

What’s incredible and testifies to Miyazaki’s genius touch is how vivid and inspirational a character he has created in a movie that is barely over 90 minutes, where we only see Totoro less than half of the time, in which he barely speaks. Totoro was such an important work for Miyazaki and its production company and its impact so immense that Studio Ghibli has since decided to redesign their logo to feature its most beloved creation[expand]

[/expand].

[/expand].

The next year saw the arrival of Kiki’s Delivery Service, yet another child-orientated movie with a deep lesson about growing up and training towards a goal. It is a wonderful movie in which Miyazaki takes the audience to Europe in his wonderful reconstruction of a fictive Croatian coastal town. Part of the storyline from Kiki was re-used by Sam Raimi in his film Spiderman 2. Peter Parker suddenly loses his powers because he loses faith in being Spiderman, just as Kiki doesn’t believe that becoming a witch is right path for her anymore.

Three years later Miyazaki created yet another tell based in the Adriatic Sea. Porco Rosso, set during the First World War, tells the story of an independent firefighter that was mysteriously turned into a pig after a deadly air fight where he saw most of his companions die. In this short tale Miyazaki paints yet another wonderful world about a time long gone. Perhaps because it was set in an Occidental environment and was also less eccentrically fantastic than its predecessors, Porco Rosso was Miyazaki’s first hit in America and Europe. More linear and shorter than his previous efforts, Porco Rosso is the work of a confident master whose actual meaning as to why Marco was changed into a pig is still to this day an unresolved mystery and a vivid source of fascination.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Miyazaki first announced his retirement from the film industry with the making of Princess Mononoke in 1997. At the time of its release it became Miyazaki’s biggest hit and critically acclaimed film worldwide. Mononoke was basically a revisited version of Nausicaä, and it was a perfect way to conclude his brilliant career. Thirteen years had passed since Nausicaä; he was now an artist in full control of his visual and narrative art, but also an artist able to handle and compose within his cultural heritage.

Princess Mononoke takes places in Ancient Japan, at the beginning of the industrial age, when a fracture broke between Japan’s dream of progress, expansion and technology and its cultural heritage and folklore. This time we follow the tracks of boy-prince, Ashitaka, who must find a cure to a curse set on him after he killed a wild animal; just like the forest and its insects where an infectious threat in Nausicaä. Ahitaka’s journey takes him to a distant land where a mining colony involved in the production of revolutionary guns finds itself pressured between the Gods of the Forest and their Human Princess San or Mononoke, and the walking army here to embrace Japan’s future through advance technology and mass destruction weapons.

Miyazaki was never an idealist and the core of his films are often laced with an infinite sadness. Ultimately, man’s hunger for conquest and progress is winning the battle against Mononoke and its Japanese’s heritage. Folkloric Gods die in the end, the men walk to their inescapable future. Twenty years later, the film still holds up visually – mind-blowingly so – and the digital revolution hasn’t affected it in any way. Princess Mononoke is a gem and one of the rare films that can truly be labelled “perfect”.

Spirited Away (2001)

When Miyazaki retired, he took the time to enjoy life and old age in the country. One summer in the mountain, surrounded by his descendants and a group o ten-year-old girls that were friends of the family, Miyazaki felt a new urge to create. He thus wrote himself out of retirement with Spirited Away, which stands as Japan’s most successful film ever made, bringing 23 million viewers to the dark rooms in Japan alone and grossing nearly 300 million dollars worldwide.

Spirited Away tells the story of ten-year-old Chihiro, who, whilst looking for the new house that she and her family are moving into, finds herself and her parents in a deserted theme park. Her parents are changed into pigs for having eaten what wasn’t theirs and Chihiro finds herself alone in a strange world full of ghosts, spirits and legends. Chihiro is forced to work for the owner of the gods’ thermal baths, the terrifying witch Yubaba. Whilst trying to blend into the odd society of weird creatures that act as her co-workers and customers in order to keep safe, Chihiro must find a way to save her parents and go home.

Rarely has a movie been more original, featuring a series of such unexpected and captivating events in the most mystical world. For me, Spirited Away is perhaps the most magical experience I have ever had at the cinema. No movie has ever captivated, enthralled and moved me as the tale of Chihiro’s journey did, to the point of leaving me in tears when the credits started rolling on the first notes of Joe Hisaishi‘s Always With Me. Those were tears of joy, as well as sadness as I realised that this magical world that Miyazaki opened for us only truly existed in the master’s imagination and good heart. Never, despite all my best efforts and intention, could I come close to finding this fantastic world Chihiro had been dragged into. As an artist, I also realised that never I could equal such a work of art.

The Wind Rises (2013)

After Spirited Away, the master retired yet again to come back once more with the adaptation of Diana Wynne Jones Howl’s Moving Castle. Yet another fantastic film in which Miyazaki returns to Europe for this tale of witches and magicians at the edge of war. It combines about all of Miyazaki trademark themes and features: witches, spells, curses, fictional lands based on ancient civilizations, war, adventure, magic, enchantment and a good moral lesson to wrap it up.

The film never quite reached the heights of the more polished and controlled works like Monoke or Spirited Away. The problem is that the adaptation of Jones’ two novels into one feature film made the movie long and dense, and the transformation of Howl/Hauru felt rushed. Too many questions are left unanswered in its conclusion, and the answers to the movie’s mysteries aren’t as clear as in Miyazaki’s precedent works.

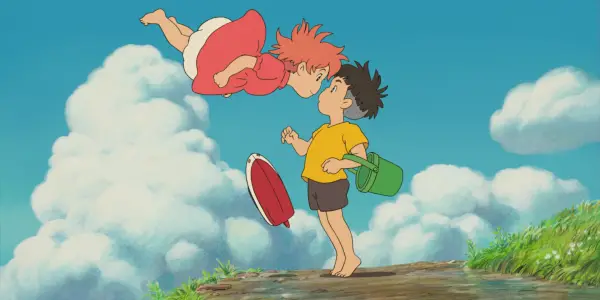

Miyazaki and his collaborator Joe Hisaishi [expand]The composer who created many of the scores for Miyazaki’s films. The scores added to creating the magical worlds, and the magical experiences – they are perhaps equal to the quality of Miyazaki’s visual art[/expand] had too much fun in the making of Howl to think about retiring this time. Miyazaki followed with Ponyo and Hisaishi created another hit with a score that was actually released prior the movie’s release and its feature song became an instant kindergarten national hit. Ponyo is a return to Miyazaki’s roots in Japan, set in a harmless child’s world where the magical fish of wizard living under the sea comes to the surface to become a little girl who befriends a dreaming boy and its lone mother.

Ponyo was another gift to the world of cinema from a master who never seemed to have more control over his art. Five years after Ponyo came the most unconventional film of Miyazaki’s career, The Wind Rises. For the first time in 54 years since debuting with the co-creation of Horus Prince of the Sun or The Little Norse Prince, Miyazaki relinquished the magical and the fantastic to deliver a sober, moving, yet somewhat controversial biography of Jiro Horikoshi, the Japanese inventor who spent his life creating instruments of war, the Japanese airplanes for the WWII, which, if they helped to protect Japan, its culture and its people, have been responsible for the death of many men and women.

Miyazaki’s last film to date is a work filled with sadness; it is the antithesis of his previous movie Ponyo. It is a movie very much unlike everything the director’s has previously created. Still enjoyable, undeniably well-constructed, designed and written, one cannot help but feeling a little bit dazed upon seeing the final credits roll and perhaps unsure of what was Miyazaki’s true intention behind its making. The movie was released to quite surprisingly indifference, in a world still in awe of the director’s work. NeitherMiyazaki nor the studio made a lot of noise about it and the movie did not benefit from a true international release (it took over one year for the movie to reach the UK and it was only shown on a handful of screens for a very limited time, in a non-dubbed version).

Miyazaki’s career is similar to the end of the genius composer Beethoven’s career. In Beethoven’s final string quarters (number 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16), in which he revisited a more formal and conventional type of music whilst at the same time completely remodeled its contours. At the time of their release, after the massive success of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, the quartets were completely overlooked, dismissed and criticised. People even labeled the old master as deaf and done for in the world of music. It took over a century for music critics to recognise the avantgarde grandeur of his final compositions, and they are now considered among the maestro’s best compositions.

The Wind Rises certainly raised some eyebrows as to its place within the maestro’s filmography but one cannot doubt the passion Miyazaki put into the film that could be his very last one. It was the first one since Nausicaä not to bear any fantastic elements and the first one since 1984 not to become a massive, critically acclaimed hit. It is a work that raises questions and divides the cinema lovers who have seen the movie. And like Beethoven’s later work, it perhaps will be considered avantgarde and genius in another century.

Miyazaki’s Future

What’s next now for Miyazaki? Was The Wind Rises a farewell in Beethovien style, or will his son Goro Miyazaki finally step up to take his father’s helm? Goro Miyazaki has already directed a couple of full-length features: Tales from Earthsea in 2006, an incomplete work which had his father Miyazaki leaving his son’s premiere in the middle of the screening, and the overlooked From Up on Poppy Hill in 2011. Hayao Miyazaki has since repeated that his son was not yet mature enough to succeed him, however, keep in mind that it took about 15 years for the master himself to conquer his art. Only time will tell if Goro can one day equal and perpetuate his father’s work of enchantment and wonders.

If you’re a long-time fan of Miyazaki, please share your thoughts on the master’s films and tell us about your favorite films or characters!

(top image source: unknown)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alexandre Thiebaut is a part time writter, a full time entrepreneur and a cinema lover. Born in the same city as the cinema, he studied the Art at the cinema Lumieres of Lyon before relocating to the UK where he manages two companies in the wine industry.