TATHAGAT: A Lifelong Quest for Truth and Meaning

A writer from Mumbai, India

There is a certain duality in our nature that is rather peculiar. As children, we cling to those who we are closest to and revel in being dependent on them. But as we grow older, so does our notion of self-identity, thereby creating in us a demand to become independent. While we might achieve a certain degree of self-reliance in our adult lives, the inherent desire to connect and bond cajoles us into forming co-dependent relationships, without which it’s difficult to survive sanely and intelligently in a civilized society. However, there are a few who attempt to break free from the clutches of attachment, and forsake the material world in pursuit of a higher “truth”. In India, such seekers are often found nestled in the mighty abode of the Himalayas – regarded as a gateway to attain the divine.

The Past Continues to Haunt

But what if midway into an individual’s spiritual quest, they are unexpectedly haunted by their childhood memories and a deep longing to connect with the past? Is the biting realization that their renounced self isn’t dead but alive in the recesses of their mind, too disconcerting to shake them to the core? In Manav Kaul‘s second directorial outing, Tathagat, an old monk – referred to as Baba (Harish Khanna) – finds himself spiraling down the rabbit hole when he receives a letter that brings to the shore a sea of buried memories and unresolved emotions/desires.

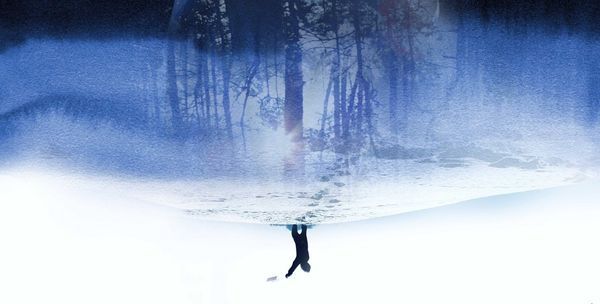

Baba’s mausi, or aunt, (Savita Rani) has passed away, the news of which sees his imaginative mind revisiting his childhood spent in her company. Kaul alternates between Baba’s carefree younger days as Suraj (Himanshu Bhandari) and his current inner turmoil, for most of the screenplay. The sun-kissed fields of the village where Suraj and mausi used to play are frequently intercut with the verdant hills navigated by a perplexed Baba.

A Poetic Awakening

When it dawns on Baba that the ascetic path of sacrifice towards enlightenment might be a sham and an escape route from one’s reality, he decides to return home. But his disciple Amar (Ghanshyam Lalsa) is shattered on learning about his guru‘s rejection of their sacred and all-consuming belief. This is followed by Amar’s attempts to persuade Baba to stay back in the Himalayas. This portion of the film feels a bit theatrical as the two monks discourse on metaphysical topics using metaphorical jargon sourced from ancient religious texts. The influence of Kaul being from a theatre background clearly shows in this stretch and a few other scenes as well where dialogues feel more suited to plays. But Kaul makes up for this hitch by eschewing the plot in favor of cinematic expression. The pristine visuals of the splendor of nature have been lensed poetically by Pooja Sharma, congruent with the lyrical theme of Tathagat. Avishek Majumdar‘s melancholic background score complements the film’s nostalgic mood and surely does aid in elevating its overall emotional quotient.

Tathagat succeeds in being an affecting philosophical drama, largely owing to the sincere and committed performances by its ensemble cast. Harish Khanna as Baba stands out from the pack for effortlessly traversing a melange of emotions ranging from guilt, pathos, compassion, joy, to tranquillity. Ghanshyam Lalsa as Amar – who later in the film decides to fast alongside Baba when the latter vows to renounce life – is effective in his role as a naive, devoted disciple. The one let down for me as regards casting was the role of mausi by Savita Rani. A fine actress in her own right, however, Rani‘s demeanor and voice in the film exude more sensuality than motherly affection. I believe if someone with a more maternal aura had been cast in her place, the warmth and purity in her scenes with Suraj could have felt more palpable and heightened my engagement with the film.

Conclusion

Like most meditative films, this one too floats a lot of existential ideas and questions to ponder. Kaul deserves to be appreciated for daring to question the age-old tradition of seeking moksha/truth through renunciation and asceticism. The reason I think this is a gutsy film is that in a country plagued by religious fundamentalism and where saints are blindly worshipped, it’s a challenging task to portray seekers as flawed individuals who in reality might be escapists. In Baba’s case, Kaul leaves no ambiguity that it is guilt that pushed Suraj to run away from his past to eventually become Baba. Whatever the reasons might have been for Amar to leave his family behind, his relative who frequents him in the mountains holds a mirror up to him. By abandoning one’s loved ones and thereby subjecting them to endless grief, in the hope of attaining spiritual wisdom, can such an individual ever get closer to the elusive “truth”? Manav Kaul‘s Tathagat leaves its viewers with this debatable thought, among others.

Would you like to watch Tathagat? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.