science

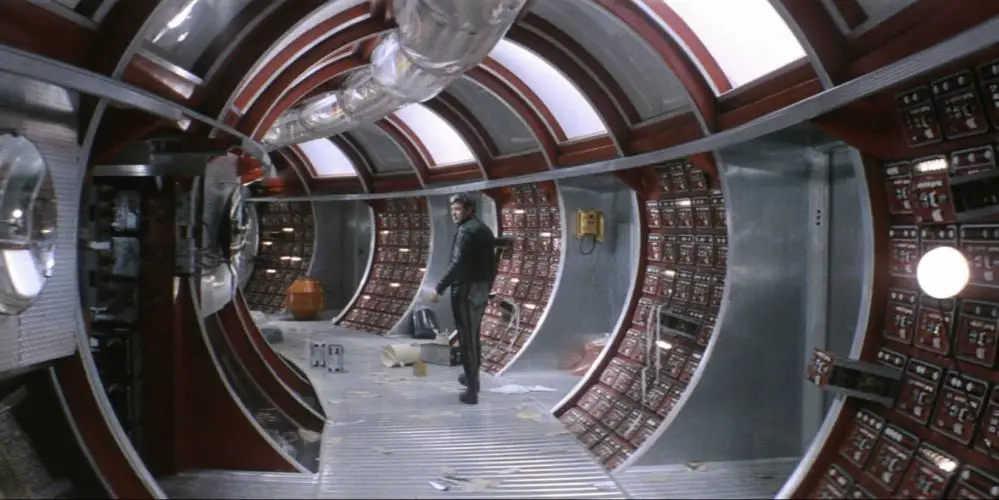

In Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris, Kris Kelvin (played by Donatas Banionis) journeys to a space station on the sentient planet Solaris in order to investigate whether the planet is still useful for scientific inquiry. Critics at the time considered Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film as the Soviet answer to Stanley Kubrick’s famed 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Two decades after the original Jurassic Park became the most successful film of all time at that point and ushered in the era of CGI, the blockbuster cinema landscape is very different. With Marvel Cinematic Universe, franchises six or seven sequels deep, and young-adult dystopias dominating the big releases more and more every year, original screenplays or adaptations of adult-oriented novels are struggling to make an impact – it is inconceivable that Steven Spielberg’s classic could have been released today with anything near the same level of success as in 1993. And so while the original film has a devoted fan base, few would have thought there was that much demand for a new Jurassic Park film, especially after its two increasingly inferior sequels.

I’ve been toiling over this review for about a week now. A large portion of mainstream film criticism has shifted towards tearing down films, blatantly nit-picking all aspects of a movie and continuously shouting nasty adjectives which seemingly constitutes as a review of a film. I get why it’s so big nowadays, being angry at or disappointed in something will always get a more humorous and memorable responses.