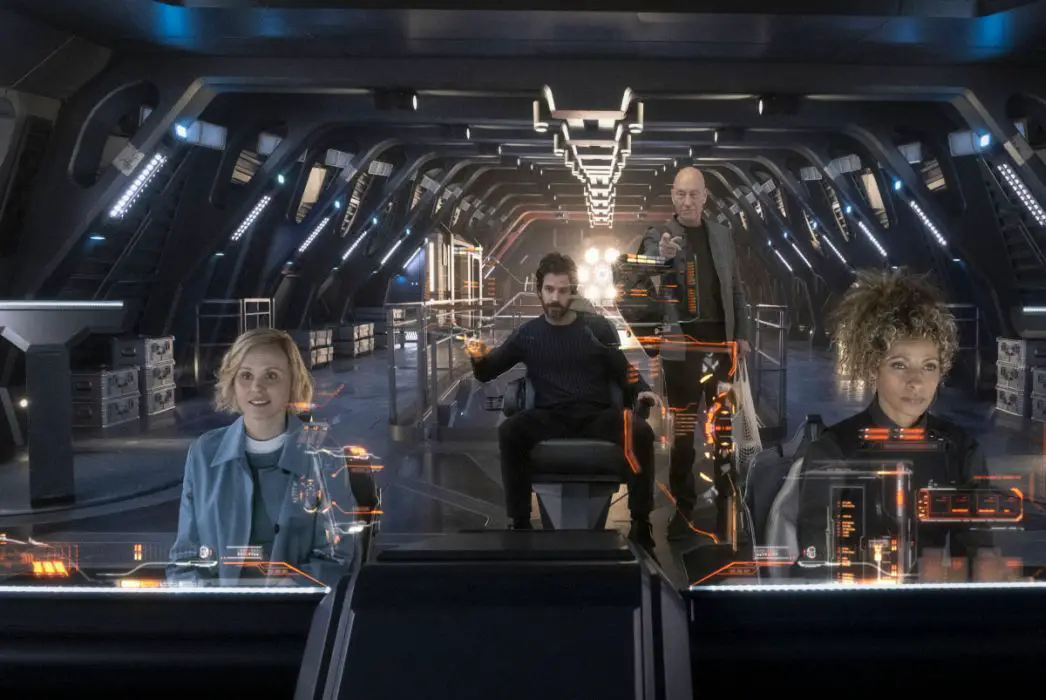

Patrick Stewart

Director Jeremy Saulnier’s debut film Blue Ruin marked him out as a director to watch, a spiritual heir to the throne of the Coen Brothers at their most violent. Like the Coens in their bloodthirsty prime, Saulnier filled Blue Ruin with borderline absurdist humour and fully fleshed out characters who would appear as nothing more than walking quirks were they not so perfectly realised. Most importantly, he achieved something that few other Coen imitators manage – he perfectly understood that the violence in their movies takes place in a moral universe, where no evil deed goes unpunished.