indie

You would be right in thinking with a title like this The Boom Boom Girls Of Wrestling would be a lot of fun even if it wasn’t very good. Made by independent filmmaker Carolin Von Petzholdt, The Boom Boom Girls Of Wrestling claims to be inspired by true events (but I’m pretty sure this is just a gimmick), and tells the story of a group of out of work actresses who train to be wrestlers as part of some kind of reality show. However, on their way to their first event in Las Vegas their bus breaks down and they are stranded in a ghost town where a mysterious slasher (dressed as chicken, because, why not?

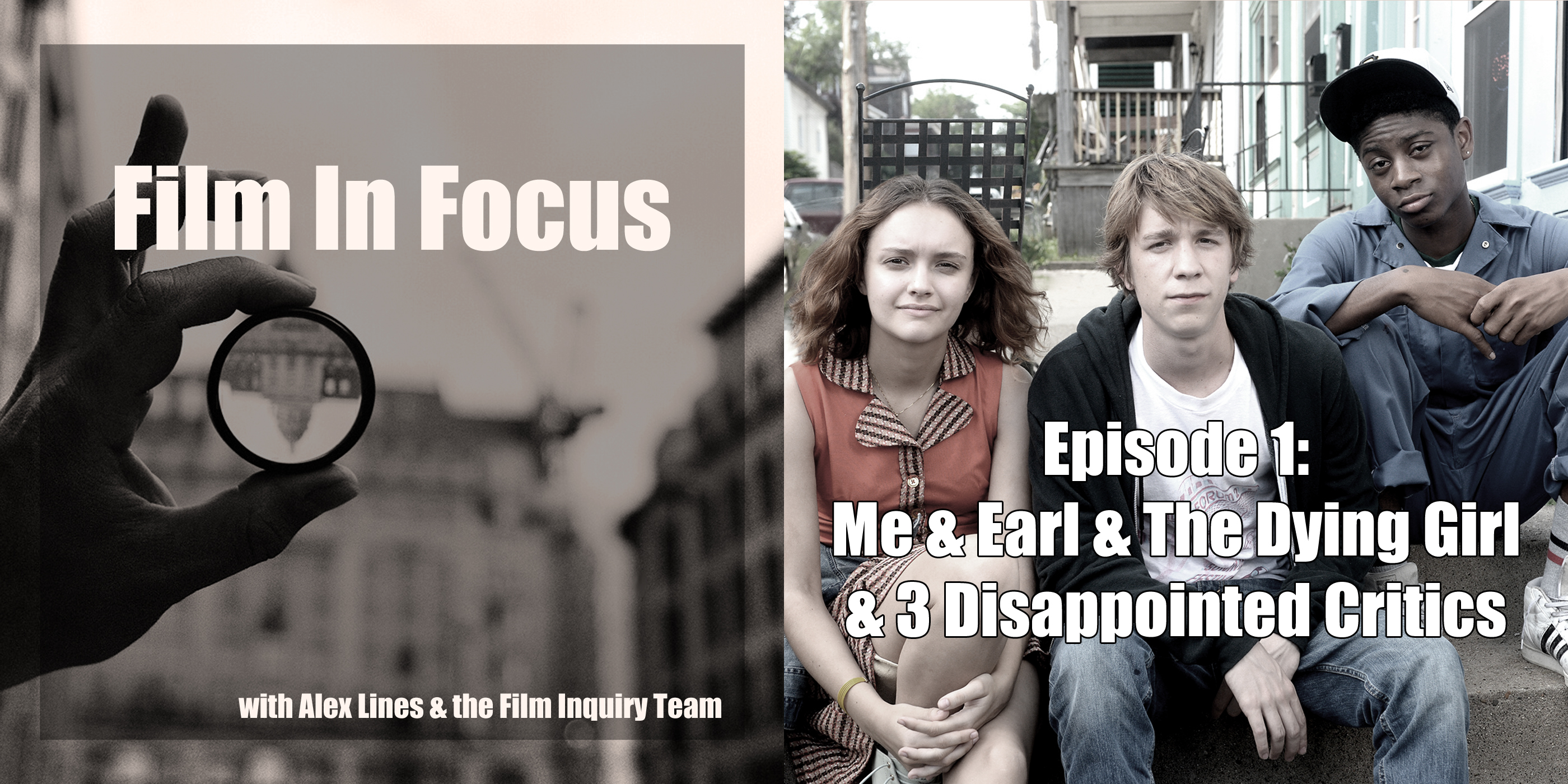

Introducing the first episode of the tentatively titled ‘The Film Inquiry Podcast’, where each episode myself (Alex Lines) will be joined by two of our writers to pick apart and discuss a different film. In our initial episode, I’m joined with Julia Smith and Alistair Ryder, who I stupidly forgot to name in the podcast episode itself. As Julia, Alistair and I were all disappointed with the 2015 indie darling Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, we talk about what exactly we didn’t like about it and try to break down who exactly the film was aimed towards.

Low budget productions always have to come to terms to the fact they are not going to be able to offer proper cinematic spectacle on a minuscule budget. A Dozen Summers instead opts to be as deliberately amateurish as possible, giving it the distinctive feeling of a movie that the twelve year old protagonists would not only wish to make, but would be capable of making. It feels aimless, rambling at even a brief 82 minutes (eight of which are dedicated to elongated end credits), but proves near impossible to dislike despite all of its clear faults.

Woody Allen’s perennial dialogue of death and futility is upon us, and, as someone who takes comfort in the recurring anguish of Mr. Allen’s films, I couldn’t be happier with his 2015 iteration, Irrational Man. He executes a story equivalent in scope to what has become one of the auteur’s main ambitions these fifty years:

Under the last government, the UK film council (which supported the funding, production and distribution of British films) was scrapped, as prime minister David Cameron cited that the initiative “wasn’t supporting films people British people want to see, like Harry Potter”. Subsequently, we have been told this has made it far harder for British filmmakers to get their movies made. As David Cameron’s Conservative government have recently been re-elected into parliament (this time as the sole governing party; last time they were part of a coalition), it is time to examine what effect this will have on British filmmakers, both in terms of how they will be able to get their films made now there is a tighter grip on funding, as well as how it will effect the kinds of films they make.

At the start of Andrew Bujalski’s latest film, Results, Danny (Kevin Corrigan) entreats his wife, Christine (Elizabeth Berridge), from the street below the open window of their New York apartment to let him back into the marital home. She closes the window, so he grabs its ledge in an attempt to pull himself up to and through the plate glass barrier. Danny, who carries Corrigan’s rosaceous, wan features, brittle hair, and generous paunch (sorry, Kevin), quickly drops to the ground.

I have to admit, I was a little excited to see that a sequel had been made to The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. I had liked it and was curious as to what had happened to the characters. But what is more, I went to see the first film with my grandmother and I knew how much she and her friends liked it.

With the blockbuster success of Fifty Shades of Grey in cinemas worldwide, many pundits are claiming that this marks a new era for “sex positive” movies – and much more importantly, the basic idea of a woman being as sexually open as her male counterparts not being a source of cinematic shame, but one of pride. It has only been two decades since what I dub the “unofficial Michael Douglas misogyny trilogy” of Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct and Disclosure hit cinemas, films that (like Fifty Shades) were successful due to their frankness of sexuality. Yet those movies were inherently misogynist in suggesting that women were mentally unstable, or just plain evil for daring to be as open about their sexuality as men.

It’s often stated that January and February are the two worst cinematic months of the year, as all of the major new releases are more often than not the terrible movies major studios have just “dumped” there. Yet it could easily be argued that the months leading up to the end of the year (“awards season” or “prestige season”, if you prefer to forget that Hollywood backslapping ceremonies exist) are equally bad. They do usually provide the year’s best movies, yet they also provide the kinds of movies that have been made cynically to get awards.