film theory

Last month it was announced that Kirsten Dunst, in her directorial debut, will be directing Dakota Fanning in an adaptation of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. In an interview, Dunst has noted that her approach in adapting the seminal text has been to avoid the ‘didactic’ and instead ‘make a life of something … you really need to make your own scenes up’. Such an approach, while entirely refreshing for me, is one that regularly receives criticism from those that view the source text as somehow sacred, and thus static and intractable.

Laura Mulvey is a feminist film theorist from Britain, best known for her essay on Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Her theories are influenced by the likes of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan (by using their ideologies as “political weapons”) whilst also including psychoanalysis and feminism in her works. Mulvey is predominantly known for her theory regarding sexual objectification on women in the media, more commonly known as The Male Gaze” theory.

Mad Max: Fury Road, the latest from Australian director George Miller, is overtly, and perhaps primarily, an action film. The vast majority of its two hour runtime is devoted to a single unrelenting chase sequence; it both drives the narrative and provides a platform for the manic and brilliantly staged action set-pieces which will define the film for many audiences.

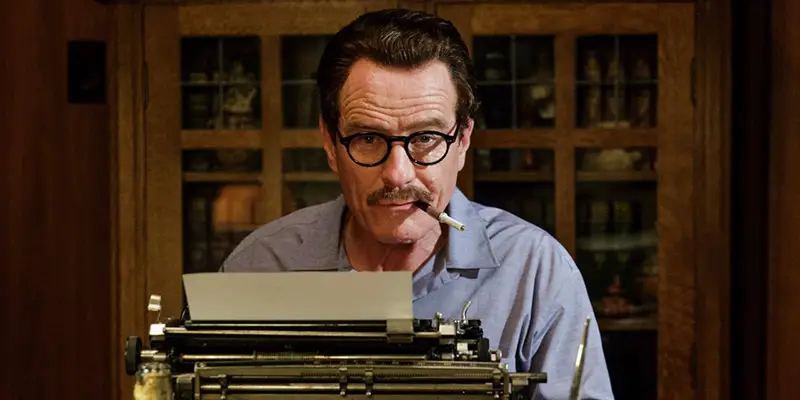

In cinema, age-gap relationships have been forever on display, from Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall to those seen throughout Woody Allen’s cinematic adventures (including his most recent Magic in the Moonlight). The age-gap relationship often takes the form of an older man and a younger girl, though there are the exceptions (take a look at The Graduate). Aside from the problematic conventions of the leading men ageing and the women remaining youthful in looks and spirit, the age-gap film poses questions about sexuality that mainstream Hollywood often shies away from.

Cult films are difficult to define, as they vary in scope, themes, genre and in just about every other way. Despite these ambiguities, it is demonstrable that the revered Roger Ebert once got the definition entirely wrong. Avatar just isn’t cool enough In his review of Avatar, Ebert described the film as an “event” that was “predestined to launch a cult.

Plot, visuals, and theme are all hugely important to great cinema, but movie audiences love characters, and they remain the most memorable aspect of many films. However, the same character types appear again and again in film – the heroes, the villains, the sidekicks and the damsels in distress. We simply accept this as a part of cinema, and of stories in general, and it’s because all stories follow the same narrative structure, according to Russian theorist Vladimir Propp.

Hollywood has always been something of a boys club. If you think about the golden era of the studio system, you always hear about larger-than-life stars and the maverick, alpha-male directors that made all the classics we know and love today. Think of pictures of giants such as Howard Hawks, Samuel Fuller, John Huston, or Alfred Hitchc*ck, who are usually seen dictating their vision with booming authority.

In this internet savvy age, successfully avoiding spoilers for movies and TV shows is a talent we all wish we had. All it takes is a brief glance at Twitter after an opening day or a TV air-date to find that what you’ve been waiting to watch for ages has been spoiled before you’ve even been granted a chance to watch it. Yet these overly enthusiastic tweeters aren’t exactly the biggest threat to my enjoyment of a film, even if they do deserve a slap across the face for making me enjoy it far less; the biggest threat is the trailers for the films themselves, which increasingly spoil crucial elements of a movie before it even opens.

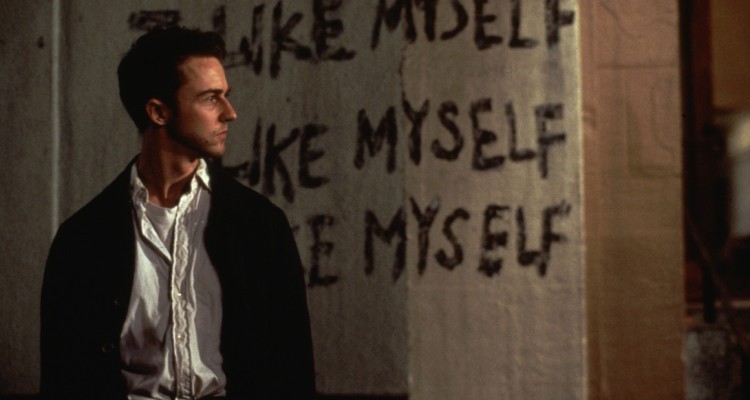

Cinema is one of the few areas of modern life where the word ‘cult’ can conjure up positive connotations: more Rocky Horror and Fight Club than Charles Manson. Screenings of ‘cult’ films gather huge, enthusiastic crowds and each have their own strange rituals and practices, such as the hilarious habit of spoon-throwing during showings of The Room.