drama

Since they first hit cinema screens in 1984, the Coen Brothers have had a firm grip on audiences and critics alike. Renowned for their idiosyncratic, high quality work, they have found themselves increasingly in demand with studios and actors, many of whom aim to make their next project a Coen Brothers film. They have written, directed and produced all of their own pictures, edited most of them, and have recently ventured into the ‘gun for hire’ realm of screenwriting, contributing to Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken, Michael Hoffman’s Gambit, and George Clooney’s upcoming Suburbicon.

A subtle yet intriguing glimpse at family built on celebrity, One More Time spins a much darker story into a lighthearted drama. Indie earmarks set the tone of the film, as the dialogue-driven character study deftly navigates each family member’s individual flaws while also allowing for a lasting bond with the audience. Pepper in the oddball charm of its male star alongside a borderline Gen X female protagonist, and the foundation is set for a well-crafted, yet easy-on-the-emotions watch.

There are few novels considered “unfilmable” that haven’t been translated to the big screen. High-Rise, director Ben Wheatley’s adaptation of J.G Ballard’s cult 1975 sci-fi novel, is the rare movie adaptation that doesn’t feel like it has been adapted, so peculiar and distinctive to the director is the increasing foregoing of narrative in favour of societally depraved surrealism.

Like all social groups, people with disability have been portrayed in diverse ways in Hollywood, from stereotypical representations in horror to genuine inspirations in melodramas. Disability is represented as a metaphor through imagery or characters’ features, or as a direct subject within the narrative. The entire concept of genre is recycled from elements within society, and the relevant features of each specifically labels the disabled into a certain character type.

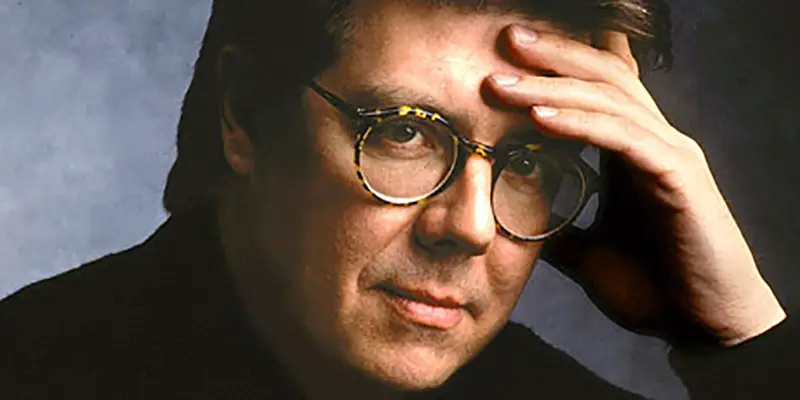

Accurately reflecting teenage experience in film is no mean feat, and there aren’t many filmmakers to achieve it like John Hughes. Born in Michigan in 1950, Hughes described himself as a “quiet kid” who loved The Beatles. Aged 12, he and his family moved to the Chicago suburb Northbrook in Illinois.

Theeb is an excellent film from this past year, and I’m afraid the precious few people will make it out to see it due to the lack of distribution. Had it not been nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar this year, I probably would have never come across this little gem. Theeb is set in 1916 toward the end of the Ottoman Empire, in a province known as Hijaz (around Saudi Arabia and Medina) where two brothers, who hail from a family nomads, escort a British soldier with a mysterious wooden box to the Ottomon railway.

Iceland is slowly becoming one of the planet’s leading cinematic nations, with many directors realising that the country’s desolate landscape is the perfect fit for sci-fi. Christopher Nolan and Ridley Scott have both shot there recently, whereas the upcoming Rogue One: A Star Wars Story was filming there last autumn.

A remake of the 1969 Italian-French film La Piscine and partly inspired by David Hockney’s ‘Swimming Pool’ painting, A Bigger Splash is the fourth feature film from Luca Guadagnino, and has already made significant waves with critics and audiences alike (sorry for the absolutely appropriate pun). Starring Tilda Swinton as rockstar Marianne recovering from throat surgery, and Matthias Schoenaerts as her ever-loving albeit boring boyfriend Paul, the two of them aim to escape life to an idyllic Italian island in the middle of the Mediterranean. No phones, no work, no interruptions.

Even though he hails from a nation renowned for its take on exploitation cinema, director John Hillcoat has repeatedly proven himself to be far more interested with the archetypes of American genre films. His international breakthrough feature, 2006’s The Proposition, was the perfect marriage of the sensibilities of Ozploitation and the most hard-boiled Westerns; for a country with no major cinema heritage, it suggested Hillcoat was a director who could put his nation firmly on the world cinema map. Instead of continuing this distinctive subversion of genre with his subsequent films, Hillcoat has become increasingly formulaic.