drama

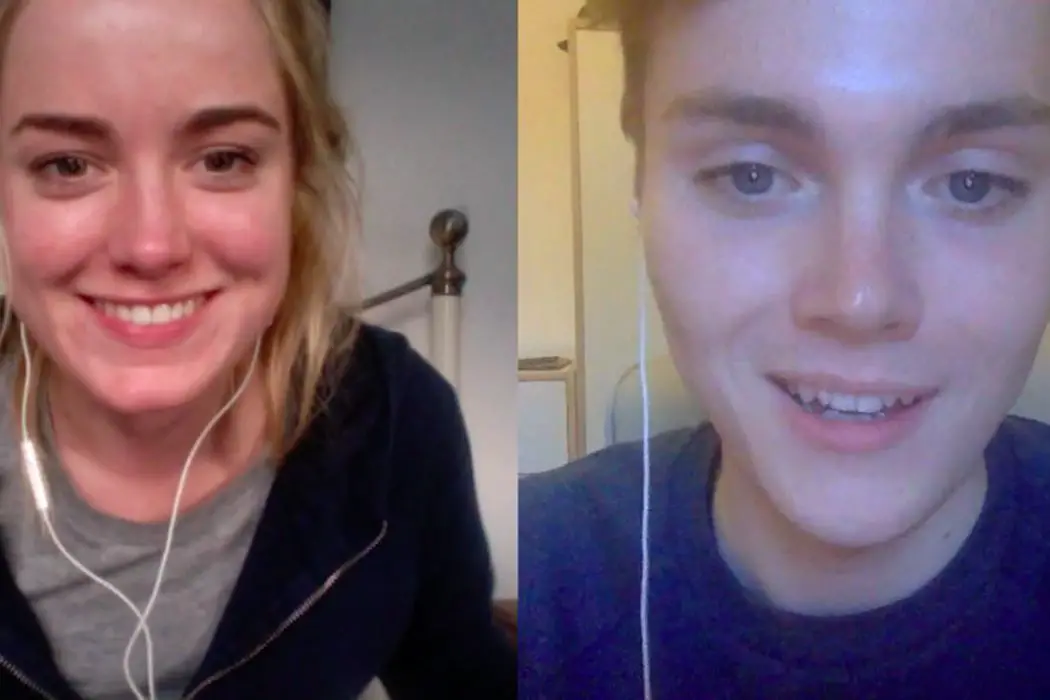

Made while studying at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama (in Cardiff, Wales) Charlie Gillette and Jack Archer’s film, These Things Never Last, is inspired by the all to scary political zeitgeist. While we have moved leaps and bounds in terms of rights and justice for people of both sexes, all races, and the widening range of sexualities and gender identifiers, a great pool of bigotry remains. This bigotry is cloaked in ideas about job security for our nations, concern over rising crime, and raised taxes.

The Godzilla franchise has had a long and storied history, dating back to the original motion picture of 1954 directed by Ishirō Honda. Produced and distributed by famed Japanese film studio Toho, the original feature has spawned multiple franchise sequels over the years, from both its country of origin and the United States. Starting with the 1956 Japanese-American remake of Honda’s original feature from only two years prior, Godzilla, King of the Monsters!

Based on the real life personal experiences of writer and director James Steven Sadwith, Coming Through the Rye offers a strange and circuitous coming of age teen drama about a young boy named Jamie Schwartz who seeks out the reclusive author of “The Catcher in the Rye”, J.D. Salinger, in 1969 New Hampshire.