Sundance Film Festival 2019 has only just begun and already there is a strong list of contenders and pretenders emerging. Last year’s festival saw the premiere of some of 2018’s strongest titles, including Hereditary, Mandy, Blindspotting, Sorry to Bother You, American Animals, and The Miseducation of Cameron Post. My first report from Sundance includes one film to watch and one massive disappointment.

Native Son (Rashid Johnson)

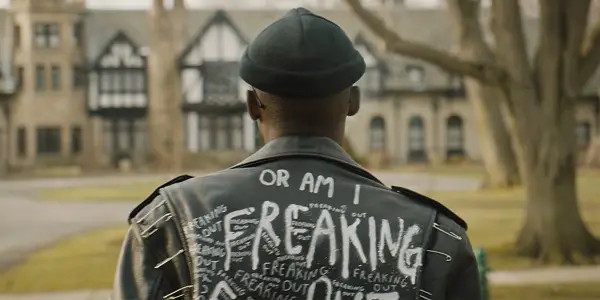

Leading the early charge as one of Sundance 2019’s best films is visual artist Rashid Johnson’s directorial debut, the emotionally devastating Native Son. Adapted from Richard Wright’s seminal 1940 novel of the same name, Johnson and his screenwriter, Suzan-Lori Parks, have updated the (unfortunately) still-relevant subject matter into a modern tragedy. Johnson’s re-telling isn’t so much a fiery indictment of institutional racism as a melancholy skewering of its impact on racial identity. Native Son is an urgent, impassioned tragedy that demands to be seen.

What makes tragedy such a powerful narrative tool isn’t what events unfold but how they unfold; more specifically in the case of Native Son, the inevitability of the hero’s self-destruction. Bigger ‘Big’ Thomas (played here in a revelatory performance by Ashton Sanders) has become an iconic figure in American literature. In screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks’ iteration, Big is a young Black man in Chicago who says he has “shit going on” even though it’s clear his life is fairly directionless. He’s a messenger for spare cash and struggles to stay just beyond the inviting grasp of what he calls “lowest common denominator stereotypical negro shit.”

His friends tempt him with drugs and the allure of easy money through petty larceny. His girlfriend Bessie (KiKi Layne) keeps a watchful eye on him, always believing he’ll transcend his modest station and fulfill his potential. The true tragedy of Native Son is that Big already knows his fate, even as he musters the strength to resist it. If the unfair biases of a racially corrupt system don’t grind him down, his own friends, already caught in the inescapable cycle of poverty and crime, will eventually wear down his defenses.

His fortunes seem to be changing when a real estate mogul (the omnipresent Bill Camp as “Henry Dalton”) offers Big the premiere gig of being his full-time driver. Big moves into a mansion in the suburbs and becomes the glorified babysitter to Dalton’s beautiful young Leftist daughter, Mary (Margaret Qualley). Soon, he’s running in unfamiliar circles of White affluence, attending political rallies, and facing charges of betrayal from his old friends back home. Big is enraged to find how easily he falls prey to the “house negro” mentality so anathema to his own values.

Those familiar with Wright’s masterpiece will quickly recognize the trajectory of Native Son. Johnson has wisely preserved most of the novel’s underlying narrative structure. His message isn’t so much about the institutional racism and prejudice in White America as the internalized self-hatred of Black Americans. You can’t tell an entire race of people they are shiftless criminals for nearly 250 years and not expect to leave psychic scars.

It’s this self-hatred and doubt that lead Big into his inescapable spiral. It doesn’t matter how hard Big runs counter to the Black culture – shunning Hip Hop in favor of Bad Brains and Beethoven or bailing out on a planned armed robbery – one bad decision after another makes him fulfill the debasing expectations set forth by White America. It’s heartbreaking and infuriating in equal measure, which makes for an uncomfortable but decidedly worthwhile viewing experience.

If Johnson fails to light any candles, Native Son is a masterful cursing of the darkness. He coaxes award-worth performances from Sanders and Layne, who make your heart yearn for a happy ending that is not forthcoming. Much like 2018’s If Beale Street Could Talk, Native Son is a story about dreams unable to puncture America’s socioeconomic ceiling. Here’s hoping that Johnson’s impressive debut receives the same accolades.

Give Me Liberty (Kirill Mikhanovsky)

Another film tackling America’s racial divide is Russian filmmaker Kirill Mikhanovsky’s frenetic day-in-the-life saga Give Me Liberty. Mikhanovsky feature debut creates a surrealistic blur of complications, triumphs, and defeats in the life of Victor (Chris Galust), a haggard medical transport driver trying to juggle competing obligations. Like a shot of adrenaline, Give Me Liberty can’t sustain its pace, flaming out in a third act that’s searching for an ending. The characters are never less than compelling, however, as their increasing frustrations mirror the exploding unrest in a segregated Milwaukee, Wisconsin plagued by riots.

This is turning into one messed up day for Victor. He drives a medical van, delivering disabled citizens to their jobs and appointments around Milwaukee. It’s a sort of traveling psychiatric practice, with Victor serving as confidante for his clients. He comforts a nervous passenger before she performs “Rock Around the Clock” at her big talent show and listens to another complain incessantly about the injustices of the world.

More urgently, Victor’s Russian grandpa and all of his geriatric friends are late for Aunt Lilya’s funeral. Against his better judgement, Victor loads the boisterous gang into his van and sets off for the funeral while making his daily pick-ups. The biggest laughs in Give Me Liberty come from the upheaval created by Lilya’s mourners, including an off-key accordion player and a gregarious huckster named Dima (Maksim Stoyanov) who may or may not be Lilya’s long-lost nephew.

Complications accumulate as a fiery wheelchair-bound passenger named Tracy (Lauren ‘Lolo’ Spencer) excoriates him for his habitual tardiness. Victor’s repeated promise to complete each task in “five to ten minutes” is less a placation than a personal mantra. If life is what happens while you’re making plans, Victor’s life is surely unfolding in five to ten minute increments.

Mikhanovsky edits and photographs Victor’s unhinged day with precise comic timing, unleashing a cacophony of visual gags that border on slapstick at times. This serves as a stark contrast to a highly segregated Milwaukee still reverberating from the aftermath of a racially charged police shooting. The two stories finally converge in the final act when Tracy (who is African American) enlists Victor’s help to bail her brother out of jail.

Until then, the racial complications are wisely pushed to the background, as Mikhanovsky celebrates the connectedness between Milwaukee’s citizens rather than the differences that separate them. When Tracy scolds Victor, “I depend on you!” she perfectly sums up the cooperation necessary to make a society work. Beyond the artificial boundaries and prejudices that plague us, we are reliant upon our neighbors to help survive the challenges of modern life. In its own small way, Give Me Liberty makes a big statement about the restorative power of basic kindness.

Late Night (Nisha Ganatra)

Late Night is a situation-comedy masquerading as a movie; a genetically engineered crowd-pleasure that aims for the middle of the road and hits the mark every single time. Perhaps these results aren’t surprising given director Nisha Ganatra and screenwriter Mindy Kaling’s extensive backgrounds in television comedy. Their admirable message about inclusion is lost in a milquetoast concoction of bland gags and uninspired speeches. There are a few laughs to be had, particularly when the deliciously wicked Emma Thompson is allowed to run amok, but this is a pedestrian affair too preoccupied with being liked to offer anything new or provocative.

Faced with the prospect of being replaced after her 28th year hosting “Tonight with Katherine Newbury,” a desperate Katherine (Thompson) needs to shake up her dusty writing staff. With her current staff composed exclusively of interchangeable White men, she demands that a “token woman of color” (Kaling as “Molly Patel”) be added to provide the illusion of diversity. It’s a ridiculous premise that might work in a sitcom but feels thoroughly contrived in a motion picture.

Miraculously, the unqualified Molly turns out to be a real crackerjack, quickly winning over her skeptical (though completely unthreatening) male co-workers and ascending to the top of the writer’s food chain. She worms her way into Katherine’s confidence by ‘telling it like it is’ and doing wacky things like sitting on a trashcan at the writer’s table. Late Night is little more than a wish-fulfillment fantasy, so we go with it.

The film’s shining moments, all occurring within its first hour, come courtesy of Thompson. Though she’s never allowed to be worse than a loveable grump, Thompson throws verbal zingers like a master craftsman. Unable to remember the names of her harried writers, Katherine simply refers to them by number. This is, perhaps, the most realistic aspect of Late Night; the horrific (yet hilarious) treatment of under-appreciated, over-worked writers.

Kaling is predictably plucky and likeable. Unfortunately, you don’t believe for a moment that her character could hold her own with a seasoned professional like Katherine. The supporting cast is strong in a sitcom kind of way, providing strategically-timed buffoonery to break up the monotony of Molly and Katherine’s banter. Max Casella is particularly effective as the hangdog Bruno Kirby-esque co-worker who takes Molly under his jaded wing. John Lithgow also has some tender moments as Katherine’s long-suffering husband who serves as her moral conscience.

The second half of Late Night devolves into a tedious slog. Faux emotional epiphanies and overwrought speeches take the place of characters actually doing things, which makes the conclusion a decidedly inert affair. There’s also an ill-advised blackmail subplot designed specifically to reference the #MeToo movement.

Though its desire to highlight the benefits of inclusion in the workplace is admirable, Late Night is geared to avoid provocation at all costs. Simply, it lacks the courage of its conviction. It’s like a timely, powerful message delivered through a comically tiny bullhorn… filled with helium.

Be sure to catch all of my reports from Sundance 2019!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.