Sundance Film Festival 2019 Report 5: MONOS, BEDLAM, PAHOKEE, THEM THAT FOLLOW, & MOONLIGHT SONATA: DEAFNESS IN THREE MOVEMENTS

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover.…

We’re still fighting through the snow and crowds to bring you as much coverage from the 2019 Sundance Film Festival as we can, but of course our team’s personal tastes still dictate our individual picks. For me, that means even more documentaries, and just for variety, I threw in a couple fictional movies as well. Here’s what I managed to catch over the midpoint of my time in Park City.

Monos (Alejandro Landes)

Thank god for the weird and wild filmmakers among us. They are the ones who pull back the veil on strange worlds, show us the humanity of monsters, and make us stare directly at our callousness until empathy slips in. That’s precisely what co-writer and director Alejandro Landes has done with Monos, a dreamlike tale of child soldiers guarding an American hostage.

The outfit in question is mostly comprised of teenagers who are loosely overseen by a nondescript group called The Organization. They have been left on a cold mountain with their charge, and as teens with a lot of free time do, they drink, have sex, and do drugs with wild abandon.

It may sound like fun and games, but even these scenes of revelry have a lingering sense of doom. After all, there’s a woman locked up in this dismal place, and the occasional check-ins by The Organization bring demanding tests of their physical and mental commitment. You know it’s only a matter of time before things take a turn, and once it does the descent goes deep.

Monos draws from the long tradition of characters loosing their minds in the wilderness, even including an unmissable reference to Lord of the Flies. For all its familiarity, though, Monos never feels stale. It’s too nightmarish in its imagery to wear out its welcome, too distanced from its characters to feel predictable. The hanging mystery of how far these kids will fall is captivating, and the fact that the tale is purposefully adrift in space and time makes it feel alarmingly universal.

A lesser film would’ve taken a more straightforward route with this premise. It would’ve spoon fed you empathetic characters, fleshed out precisely what brought these kids here, and made them all into wayward lambs in need of saving. Landes is apparently uninterested in such a simple world, so he lets everyone, including the captive woman, show their warts. What this does is lend the film a fairy tale-like quality; there is a morality question being posed here, and it’s one that won’t hit you until the film’s final shot.

Landes’ patience with this story will be trying for some, but the brilliance of his pace is that it allows focus to shift from character to character almost imperceptibly. We never get close enough to truly understand any of them, but each are given moments of turmoil, leading to choices that are sure to surprise you.

All of the cast handle their characters with remarkable ease, making it easy for the audience to understand that they do have a history we aren’t privy to. Thanks to them, these people never come across as sketches (always a danger with this kind of film) but instead feel like enigmas left to unravel.

The entire film asks you to unravel its meaning, and your enjoyment of it will depend on how open you are to doing some of the heavy lifting. Watching it is about letting its obtuseness wash over you; it’ll likely be after the credits role that you decide whether this brutal film was worth it.

Bedlam (Kenneth Paul Rosenberg)

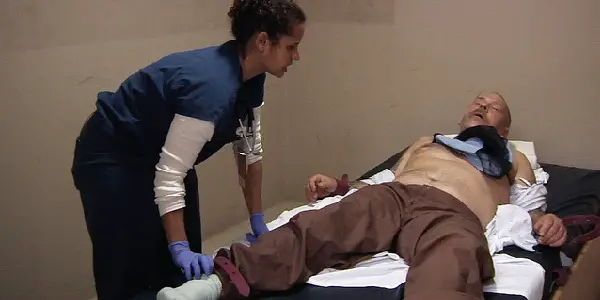

It’s hardly a secret that mental health treatment in America is lacking, but while we’re getting better at treating depression, anxiety, and other disorders that affect wide swaths of people, little has been done for the severely mentally ill. Schizophrenia and other forms of psychosis are still a revolving door of temporary treatments and setbacks, which is where the documentary Bedlam lays its distressing focus.

Director Kenneth Paul Rosenberg is a psychiatrist himself, so he knows the ins and outs of how the profession has left these people by the wayside. The decisions that brought us here go back hundreds of years, and he covers this history with the ease of someone well-versed in the timeline. However, he is aware that facts aren’t going to push people to make changes, so he leans on a group of expertly selected professionals, family members, and sufferers to get the audience emotionally involved in the tragedy.

Originally conceived as a documentary about an L.A. psychiatric emergency room, Rosenberg quickly realized that this scope was too narrow for the problem at hand. Only by expanding out into the wider world could he show what is truly going on, and so the film sprawled into a years-long look at the myriad of ways our systems fail good people.

It would have been easy to loose focus in this expanse, but Rosenberg shows great instincts for how much audiences need to see. There’s wrenching footage of people in the throws of psychosis set against periods where they are moving through the world just fine, and Rosenberg crafts each of these journeys into a poignant example of some facet of the problem. This allows him to touch on everything from housing issues, pharmaceutical side effects, and the deadly intersection between mental health and race, a scope few documentaries on the subject achieve.

This is partially due to how eloquent his subjects are, either through developed speaking skills (one of the family members is a co-founder of Black Lives Matter) or their willingness to speak frankly about their experiences. A psychiatrist at the ER is especially striking, as through her we get a glimpse of the toll this failure places on those stubbornly refusing to give up the fight.

If all of this sounds a bit overwhelming, well, it kind of is. Bedlam isn’t shy about how many errors we’ve made or how much work it will take to correct our course, but thanks to Rosenberg’s care in crafting this documentary (and in giving us the occasional humorous edit), you’ll leave feeling more resolved for changed than bogged down by defeat.

Pahokee (Ivete Lucas, Patrick Bresnan)

Vérité documentaries are having quite the moment right now, with people recognizing the need to shift narratives about those being stereotyped and maligned in the media at large. The style of applying minimal perspective and allowing the audience to see something close to real life is a way of pushing back against the boxes people are put in, and audiences with an appetite for quiet, patient films are lapping them up.

This mood should benefit Pahokee, which follows four high school seniors from the small rural town of Pahokee, Florida. Nothing is done to dramatize their lives, instead letting commonplace moments stand on their own. Like so many of these films, though, its subjects have been carefully chosen to observe those that often go unobserved, and because of that, this slice of life takes on more potent meanings.

College applications, a homecoming queen competition, and a child running among one of the teen’s legs hint at their ambitions, which often exceed what they grew up with. It’s the American dream playing out in reality, not a dream of the shining lights of Hollywood or the billions to be found in Silicon Valley but of the steady careers and the comfortable lives to be found outside the marsh.

Even with these ambitions, the kids are still kids, and they get riled up over things adults may erroneously think of as inconsequential. Pahokee treats them with the respect they deserve, though, and in doing so reminds you of your own memories from years gone by. School rivalries, athletic triumphs, and personal slights do have a tendency of sticking in your mind, and Pahokee manages to capture their import to the individual without blowing them up into monumental events.

This refusal to make their subject’s lives into something more than commonplace is what makes this style of documentary so effective. They aren’t showing you a pillar or disgrace of a community but the multitude of regular people who exist, and the basic humanity that shines through is what overcomes the boxes people may try to put them into.

The low-key nature of the story also means there’s a great need to edit judicisiously, as only those who really dig this approach will be happy to sit through a long film about everyday life. It’s here that Pahokee shows some rough edges, including a few too many scenes that repeat underlying themes and cause the film to drag in its middle section.

Still, the kids of Pahokee are so winning and the eye of directors Ivete Lucas and Patrick Bresnan are so attune to the consequential aspects of teen life that it leaves you with several takeaways worthy of your time. Of course, with this type of film, it’s up to you to find those meanings in the mundane.

Them That Follow (Britt Poulton, Dan Madison Savage)

Is it too much to ask that the Appalachian snake handling movie be a teensy bit exciting? Apparently so if you’re talking about Them That Follow, a dull, lifeless drama set amid a reclusive church.

There’s an admirable reason for the subdued take: directors Britt Poulton and Dan Madison Savage wanted to make the maligned religious community approachable, so anything involving the deadly snake rituals is presented with the utmost care. Problem is that the ardent beliefs of this church is also the main source of tension, so treating it with kid gloves drains the movie of narrative drive.

The film centers on Mara (Alice Englert), daughter of the pastor and entrenched believer in everything her father teaches. Except, of course, when it comes to love, having fallen for the religiously ambivalent Augie (Thomas Mann) and taken the relationship far enough to be secretly carrying his child. It’s an untenable situation, one that forces Mara to confront the harsh realities of her father’s strict religious teachings.

The showdown in the film should be between the allure of religion and of love, a rife battleground that only gets more complicated the deeper the religious beliefs are entrenched in the surrounding community. Both sides need to have a palpable pull, but Them That Follows fails to make either seem very attractive.

The fact that there is no chemistry between Mara and Augie is unfortunate, and this seems to be a case of poor casting (Englert and Mann just have nothing going on between them) combined with some trite dialogue. But the more deadly failure is the subdued take on this flamboyant religion, which bleeds directly into the other key relationship in the film: the one between Mara and her dad.

Casting Walton Goggins as the charismatic church leader/demanding father should have been a slam dunk; he can bring an air of certainty to any room, the kind that can convince people that true belief will protect you from deadly snakes. It’s remarkable, then, that even he is drained of his usual energy, and one is left wondering why anyone is willing to follow this man (Olivia Colman isn’t even convincing as one of his most ardent believers, and if the job too hard for someone like Colman, then you know the filmmakers haven’t done enough to support their actors). By not capturing the sincere beliefs of the people who practice these rituals, the movie entirely fails at both making the practice understandable to audiences at large and in giving Mara any reason to stay.

There’s never a moment in Them That Follows where you doubt that snake handling is an unnecessary risk, so by the time it finally revs up to its inevitable ending (which it does admirably go for, puss and all), it’s too little, too late. This is a poorly executed mess, and one can’t help but feel let down by the blandness of it all.

Moonlight Sonata: Deafness in Three Movements (Irene Taylor Brodsky)

The deaf community has often been left out of films and filmmaking by the nature of their form; movies rely heavily on sound, and without this crucial element most people assume you won’t get the full effect of the art form. Many hearing people think the same thing about life in general, being unable to imagine navigating the world without the audio cues that are constantly hitting us.

Moonlight Sonata: Deafness in Three Movements pushes against this ostracization, with director Irene Taylor Brodsky turning the camera on her own hearing-impaired family members to show what their experiences are actually like. This leads to a complicated portrait of generational differences, one that frustratingly only scratches the surface of lives we rarely see on screen.

This, of course, isn’t entirely the fault of Moonlight Sonata. No one film shouldn’t have to encompass an entire community, but when filmmakers so rarely step into this experience (and even fewer deaf filmmakers are allowed to make films themselves), it’s hard not to go in expecting a lot.

Brodsky does her best to lower this expectation by giving the film a fly on the wall feel, with the camera roaming around her house as her eldest son, who wears a cochlear implant, grows up in an environment entirely different than his deaf grandparents. Their interactions are the most fascinating aspect of Moonlight Sonata, particularly as the grandparents try to pass down lessons they believe are essential for a deaf person to a kid who has spent his life hearing thanks to technological advances. The boy takes these in with a bored air; kids are just kids, after all, and trying to get them to understand the world outside of themselves is always an uphill battle.

Keeping in mind that these people have far more going on in their lives than their deafness is both an asset and a weight to Moonlight Sonata, as we get to dip into other moving arcs that took place while filming. Most distressingly, the grandfather begins showing signs of dementia, and his deterioration is a universal story everyone can latch on to. So is the son’s impish way of getting older, leading to some hilarious moments that keep the film from getting too serious to be a good time.

The issue is that Brodsky doesn’t bring these together in any sort of cohesive way, ostensibly trying to structure the film around her son learning Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata (a piece he wrote while losing his hearing). She fails to find through-lines within the material, though, and that gives the film a disjointed feel.

There’s more than enough affable scenes to make Moonlight Sonata worth flipping on some lazy afternoon, but don’t expect any revolutionary change in the way deaf people are portrayed on screen. We are still waiting for that big shift, and considering that Brodsky is as intimately aware of the way deafness affects life as any hearing person can be, perhaps this proves that it will take a deaf filmmaker to really change things.

That’s another round of Sundance films in the bag. Did any of these capture your interest? Let us know in the comments and keep up with the rest of our reports from the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover. He's perfecting his cat dad energy.