Sundance Film Festival 2023: KIM’S VIDEO & AUM: THE CULT AT THE END OF THE WORLD

Soham Gadre is a writer/filmmaker in the Washington D.C. area.…

The start to my 2023 Sundance Film Festival was with a pair of documentary films that I found to be a little less than satisfying. Both of them try very hard to drum up the interesting and unexpected sensational webs that surround their enigmatic central figures – a video store clerk and a religious doomsday cult leader. Do they succeed? Well, sort of. In an era where documentation and sourcing is often pressed to create controversy, if only to increase the odds of selling the film to a popular streaming service that plants its flags on this type of stuff, both of these movies utilize a lot of editing and plotting techniques to make their stories as narratively exciting as possible. Unfortunately, this comes at the expense of keeping things running on the surface, never truly piercing the heart or minds of the cultural sensations that are the core subject matter.

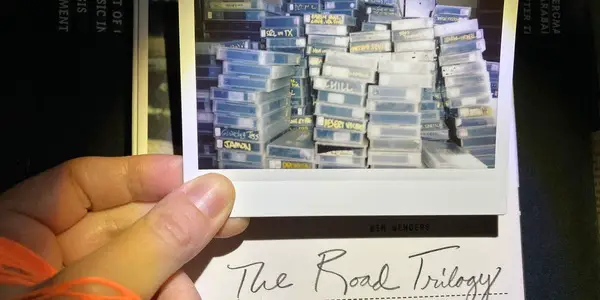

Kim’s Video (David Redmon & Ashley Sabin)

In the documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010), most of the recordings are by Thierry Guetta, a compulsive filmer and lover of street art. Banksy, who ended up directing the ultimate film, realized that despite Guetta’s passion and incessant love for recording and excavating everything in the art he found fascinating, had no focus or aim with his material. It all seemed like just a pile of “stuff”. Likewise, much of the film Kim’s Video is scattershot in its approach to try to weave in a wealth of cinema influence and love of its filmmakers – David Redmon and Ashley Sabin – to a semi-heist documentary about a community’s beloved video store, its owner, and a mystery of its videotapes that played in a small town in Italy.

This is a documentary that runs off of passion, nostalgia, memories, all of the intoxicating fumes that shape cinemaholics like the filmmakers into the adults they are today. I can sympathize with this. There have been many movies I watched that changed my life, gave me a new perspective, and turned a corner for me, and as schmaltzy as it is to say, these fictional works of art are something I owe a great deal of my emotional existence to. That’s why it’s a tall task to ever focus on them, there are so many and they’re so all over the place. In Kim’s Video, scenes whiz by, cultural references fly in your face fast and loose like Ernest Kline’s Ready Player One, and the actual cultural effect of the titular video store, a former landmark of East Village that touched the lives of many of its card-carrying members, is left as a sort of “you had to be there” supplement. It wants to be everything at once and doesn’t give time to linger and absorb Kim’s effect on the cinema culture, especially in the age of physical media endangerment.

Redmon’s narration doesn’t help matters in its awkward, repetitive, and tonally flat delivery. One of the major drawbacks here is the fact that there just isn’t good writing backing the visual smorgasbord of material. There’s no verbal or grammatical thread to weave its images or words to a point, whether it be about the value of video stores, the value of physical media in a dying cinema landscape, or the importance of community spaces in culture. These ideas all brew within the film but are left hanging as individual mentions, not realities that are in conversation with each other. Instead, the movie seems more concerned with describing every aspect of itself through sequences in other movies, not by juxtaposing imagery or symbolism but by using the word “like” a thousand times to connect them. The passion is inherent and appreciated, but is akin to the experience of walking around a video store without having a plan of what you want to rent.

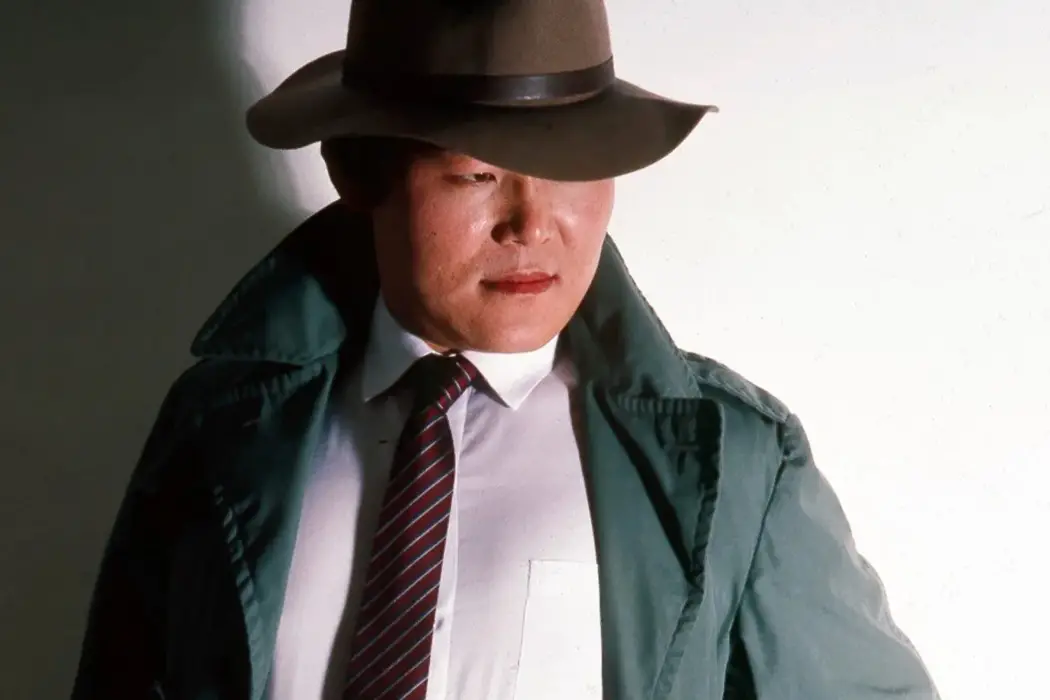

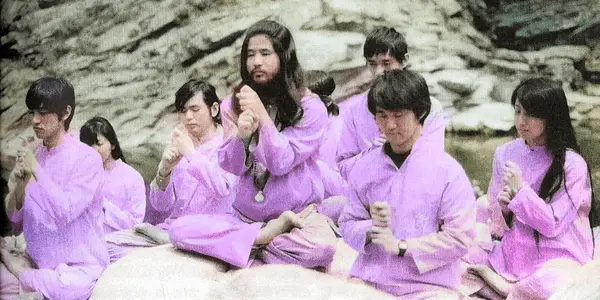

AUM: The Cult at the End of the World (Ben Braun & Chiaki Yanagimoto)

Ben Braun and Chiaki Yanagimoto’s documentary takes an unexpected approach in introducing the audience to AUM initially through the words of one of its most prominent and powerful members, Fumihiro Joyu. He was the main spokesperson for the cult, a job which mostly entailed simply reciting verbatim the thoughts, ideas, and opinions of its totalizing leader Shoko Asahara. One of the main benefits of having Joyu, who is still at large and has started his own religious group The Circle of Rainbow Light, which claims to be peaceful and unaffiliated with AUM, is that he is willing to talk, and is someone who isn’t particularly shy about detailing the activities that he conducted on behalf of Asahara.

Aum: The Cult at the End of the World is a pretty straightforward “talking heads” documentary, taking as many angles as it can through a comprehensive understanding of the cult and its most infamous crime – the 1995 Tokyo sarin gas attack. We get reputable investigative journalists like Andrew Marshall of the Tokyo Journal and David E. Kaplan who wrote the book this documentary is based on, Nagaoka Horiyuki who is the head of a victims association seeking to give rehabilitation to former cult members, and Tsutsumi Sakamoto, a lawyer tasked with pressing charges against Asahara and who’s family became victims of a cult-sponsored murder.

The documentary tends to lean a bit hypocritical in sensationalizing certain events and revelations with clever editing, despite media sensationalization being one of the purported aids of Asahara and Aum’s rise to fame. It also tends to briskly tour-guide its audience through the account of events, social influences through foreign policy and post-war disillusionment, as well as philosophical considerations to examine the cult and its effect but hardly digs the surface. In a landscape of over-saturation with true crime documentaries, AUM doesn’t necessarily stand out but it does serve its informative purpose with economy.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Soham Gadre is a writer/filmmaker in the Washington D.C. area. He has written for Hyperallergic, MUBI Notebook, Popula, Vague Visages, and Bustle among others. He also works full-time for an environmental non-profit and is a screener for the Environmental Film Festival. Outside of film, he is a Chicago Bulls fan and frequenter of gastropubs.