Staff Inquiry: Our Favorite Opening Credits

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover.…

Most credits aren’t worth salivating over. If they aren’t done with care, then opening credits feel like the laundry list of contractual obligations they are, accomplishing nothing but delaying the true start of the film and our submersion into another world.

The savvy filmmaker, though, knows that credits don’t have to feel wasteful. They can establish tone, foreshadow events, and subtly position the audience right where the filmmaker wants them. A great credit sequence can become an indelible part of the film, and these are our favorite examples of opening credits done right.

Becky Kukla – The Shining (1980)

Visually, The Shining’s opening credits could easily be mistaken for a travelogue film, showcasing the beauty of the American wilderness. From glassy lakes, to snow capped mountains, we soar through various natural wonders, finally resting before a simple yet sprawling hotel. ‘Welcome to Your Holiday’.

Stanley Kubrick is likely turning in his grave as I compare one of his masterpieces to a travel guide, but of course the opening of The Shining is nothing of the sort. We are led through incredible landscapes, but this is imperative in setting up the Outlook Hotel as geographically isolated; Kubrick wants the audience to fully understand the geography of the surrounding areas and of the hotel itself.

The camera flies along at considerable speed, catching up with a tiny yellow car which, at times, is barely visible on the screen. We are the camera, the persistent force following the car on its winding journey to the middle of nowhere. As we catch up, the turquoise blue titles begin to scroll upwards. The colour gives a calming impression but combined with the intensity of the camera and the score, we are left with a feeling of severe discomfort. It’s by no accident that Jack Nicholson’s credit appears just as the camera overtakes the car; we now know that he is the one driving it.

It is the music, though, which really drives home the sense of foreboding. The trumpet motif plays again and again, already setting us up for a continuous repetition throughout the film – a sense that we may just be going round in circles. As the score builds, a screaming is heard – not dissimilar to Wendy’s later screams of terror at the actions of her husband, Jack. Combined with the floating camera, the music evokes absolute horror from the first frame of the opening credits – even though we are not quite sure what we are horrified about.

Even including that inconspicuous helicopter shot (which has its own conspiracy theories…) you can’t deny the power of The Shining’s opening credits.

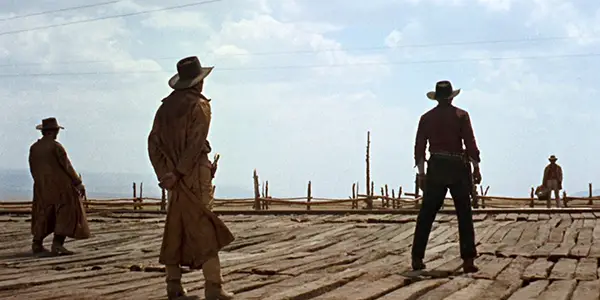

Dave Fontana – Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

A rotating wheel spins in a constant drone. Doors swing on their hinges. Gusts of wind blow through open windows. A fly incessantly buzzes. Water drips from a hanging ceiling. Empty stares emanate from behind cold, lifeless faces.

All these and more are just some of the images you will see in the first ten minutes of one of my all-time favorite films, Once Upon a Time in the West. In fact, the only dialogue which occurs in these scenes, which are interspersed with the film’s opening credits, are the shrill objections from a senile old man attempting, in vain, to receive compensation for goods taken by a burly cowboy.

This opening scene, which is set entirely within a nearly vacant train station, sets the tone for the film to come, which often lapses into silence, with nothing but surrounding noises of the desert building tension (that is, when Ennio Morricone’s wonderfully nostalgic score isn’t occupying these in-between moments). The film, which is itself a pastiche of older Westerns and also an undeniably brilliant standout in the genre, portrays the combined grittiness and mythos of the American Old West in a uniquely modernized way.

The West, in contrast to the grand scope as it is portrayed in some films, was a brutal, lawless place, where nothing is quite as it seems; criminals can sometimes be allies, such as Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, the strong-willed hero is far from perfect, seen with Charles Bronson‘s Harmonica, and friendly faces can be despicably evil, such as Henry Fonda’s blue-eyed Frank. It was far from an idyllic environment, and was often cold and empty, a place where lives were shattered, criminals reigned free, and legends were born; yet out of this also came the birthplace of the modern world, represented through the strong spirit of Claudia Cardinale’s Jill McBain.

Sergio Leone’s masterpiece is slow, brutal, and at times even an uncomfortable watch, yet it is, from the very opening credits, an undeniably enthralling cinematic experience.

Arlin Golden – Do the Right Thing (1989)

No other movie looks like Do the Right Thing, and that all starts with the opening credits. Beginning with a misdirect, a down tempo saxophone refrain over the production logos, before being interrupted by the scratching of Terminator X. Fight the Power is the film’s anthem, and the opening credits introduce an association with this song and conflict.

In a movie that sometimes feels like theater, these credits are an overture. We see a silhouette repeatedly transposed across the frame like something out of a Maya Deren film. The camera dollies in rapidly on a woman who at the time would have been unrecognizable unless you were an astute viewer of Soul Train. Taking place in front of a translight of a Brooklyn brownstone bathed in red light, the sequence is Spike Lee’s homage to Hollywood musicals, but its star Rosie Perez subverts the role of the smiling female lead as she remains fierce and expressive throughout the credits, even donning the garb of a fighter as she shadowboxes for the camera. The match editing, switching outfits cut to the choreography, which will be familiar to any fans of music videos, and there’s no doubt in my mind that this sequence is far superior to the video Spike ended up directing for the Public Enemy song.

There is a 1 to 1 relationship with her facial expressions in this sequence and mine when I dance, when I think I’m always aspiring to be Perez; shes my platonic ideal of a dancer, and when watching this I recognize I’ve pretty much stolen every move I have from her. It speaks to her depth as a performer that she doesn’t even need her most dynamic element, her voice, in order to fully command our attention; her physicality is more than enough.

Laura Birnbaum – Nocturnal Animals (2016)

It’s hard to talk about Nocturnal Animals without mentioning the opening. It is a sequence rich in sumptuous splendor; featuring naked burlesque performers, donned only in minimal American apparel with celebratory hats, American flags, and sparklers. It’s over the top, outlandish, and alluring – undoubtedly bringing many question as to its purpose.

This lavish spectacle of joy and excess contrasts with Amy Adams’ character, Susan Morrow, who is completely detached from the triumph of personal expression. Despite the material abundance, she’s emotionally absent in both affect and in personal fulfillment; listlessly living in a state of ennui for her job, her marriage, and the absence of an artistic outlet. She’s stuck in the tedium of dissatisfaction, condemned to a spiritual and emotional Sisyphus of her own making by way of her past and her present.

Antithetical to this is Jake Gyllenhaal’s character, Edward Sheffield, who we learn that unlike Susan, pursued his artistic dreams; the embodiment of which being the novel that he dedicates to her. He has used creative writing as a vessel to express the pain he feels Susan, his ex-wife, put him through. It is the ultimate revenge – to vulnerably present the creative manifestation of his passion and pain in full exhibition and splendor, just as the women in the title sequence have also done.

Edward, like the naked women who usher us into the film, exposes himself to the audience and to Susan. This struggle between repression and expression is the overriding theme in Nocturnal Animals. In a stylized noir thriller, the slow-motion dance of big, naked women is certainly unexpected, but is ultimately an artistic outlet for director Tom Ford himself.

Linsey Satterthwaite – Catch Me If You Can (2002)

There is something about the animated title sequence of Catch Me If you Can that grabbed my attention and lingered in the memory. Perhaps because it adds a playful edge to a Spielberg film that you don’t often see.

The title sequence was created by French designers Florence Deygas and Oliver Kuntzel, who deployed traditional methods in favour of cutting-edge technology, to mimic the ’60s setting of the crime caper about the exploits of con artist Frank Abignale Jr. Using silhouettes of the film’s characters from hand crafted stamps, similar to those that were used by Abignale Jr. himself, the opening credits play out like a mini version/prelude to the forthcoming film.

The titles blend seamlessly into the graphics, all coloured with a ’60s pop palette that has echoes of the work of legendary artist Saul Bass. The ’60s panache also allows John Williams to veer from his usual grand, sweeping scores to something more akin to the period. By incorporating jazz into the music it feels both stylish and mischievous and fits the visuals perfectly, creating an unforgettable sequence of cinematic magic.

Such was the impression of these opening credits that they were even parodied in The Simpsons, a surefire way to know that something has been created that is so memorable and striking that it has seeped into the pop culture consciousness.

Akemi Aiello – Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010)

The loud and eclectic garage (or living room) band sound captures your attention as you’re pulled back and dropped into the opening credits, where you meet Scott Pilgrim and the world of the story. Character names roll out like a projector at high speed. The bright images flash to punk rock music, sending you into an overstimulated trance.

Though the opening credits look like an explosion of colors moving at rapid speed, they are specifically designed to symbolize the characters. Some are obvious, like swords for Knives Chau, while others flash onto frame and vanish like a subliminal message. The credits foreshadow the characters and the story that is about to unfold, while also setting up the tone and style of the movie.

Scott is an average guy that is supposed to be boring, and until he meets Ramona the movie can be dull underneath the lively editing. But the credits give the big bang moment in the beginning that makes you want to watch the rest of the movie.

I am a huge fan of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and a part of me believes that I’ve been hypnotized to love it by the credits. The homage to old film reels as well as the use of rambunctious but clever animation perfectly demonstrates the marriage of the comic book with the screen. They’re the kind of opening credits that make you Google for the meaning behind them and watch frame-by-frame breakdowns. Then, after you learn everything about them, you watch the movie to find all the parallels.

Even though I’ve seen the movie hundreds (okay, it’s closer to thousands) of times, I still haven’t caught all the symbols, and until that day, I’ll watch it a thousand more times.

Eric Bernasek – Troop Beverly Hills (1989)

Troop Beverly Hills (1989) comes from an era of throwaway comedies with premises too ridiculous to take seriously, from Adventures in Babysitting (1987) to Mannequin (1987) to Weekend at Bernie’s (1989). It features Shelley Long – in the midst of her five-season run as Diane Chambers on the legendary sitcom Cheers – playing a soon-to-be-divorced Beverly Hills mom who hopes to anchor her life and win respect by becoming the leader of her daughter’s troop of Wilderness Girls (an intellectual-property-free version of the Girl Scouts).

It’s fun and insubstantial (and has probably stuck with you more tenaciously than it should if you were born some time in the mid-seventies to early-eighties.) But this mostly-forgettable movie features opening titles worth remembering, with animation produced and directed by Bill Kroyer, whose studio Kroyer Films was responsible for a couple other memorable title sequences – Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989) and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989) – as well as a film favorite of ’90s kids, FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992).

The titles for Troop Beverly Hills are actually the work of several animators, each one of which worked for landmarks in animation like The Simpsons, Animaniacs, and perhaps most crucially, The Ren & Stimpy Show. That show’s creator, John Kricfalusi, was involved here, and the titles bear some of the distinctive features of his style, including a retro feel, particularly in the look of the titles themselves, which are reminiscent of 1950’s signage now closely associated with diners and drive-ins. (That retro feel is helped quite a bit by Make It Big, a song written exclusively for the movie by the Beach Boys, who were then enjoying a resurgence in popularity on the strength of their hit Kokomo, itself featured in another improbably successful ’80s movie, Cocktail (1988).) Kricfalusi’s style is also certainly there in the cartoony exaggeration of the shape, movement, and expressions of the sequence’s characters.

But a successful title sequence is more than style, and the biggest strength of this one is how, through a series of brief sight gags, the animation establishes the mood of the film and helps to illustrate its primary theme, namely the perception of its main character as a ditzy and incapable woman who uses her unique Beverly Hills-ian skill set to upend her rivals’ expectations of her and her young troop of underdogs.

Amanda Mazzillo – The Brothers Solomon (2007)

Bob Odenkirk directed and Will Forte wrote my choice for the best opening credits sequence, The Brothers Solomon. This film opens with ridiculously simply credits, using the universally abhorred font Comic Sans. This font choice brings the awkward credits to a whole other level, which perfectly sets up the film. A film as divisive as this deserves to have credits as aesthetically jarring as this.

The soundtrack to the sequence is the Flaming Lips’ The Yeah Yeah Yeah Song, which works incredibly well with the opening credits, slowly building up as the sequence continues. The amateurish quality of the credit sequence adds to the humor while helping the audience decide if the film is for them or against them. If the combination of Comic Sans, a solid green background, and the obnoxiously smiling faces of Will Arnett and Will Forte doesn’t make you laugh, the film is outright telling you to turn away.

If the credits draw you in, causing a grin to grow across your face matching that of the two Wills, the film might be the right mixture of strange and awkward for you. I fall into the second category, making these rather simple credits the most memorable and greatest I have ever seen. Whenever I watch this credit sequence, I laugh and think about how I shouldn’t be laughing as much as I am. The credits pull me into the film, cheering me up almost instantly, and making me remember why I watch this film when I’m feeling down.

Sam Wilson – Casino Royale (2006)

The opening credits that kick-started the new era of Bond, the expertly designed title scene for Daniel Craig’s first venture as 007, are my favourite credits of all time. Beginning with the iconic gun barrel sequence and launching into Chris Cornell’s song You Know My Name, there really could not have been a better way to restart the franchise. Four years after the disappointing Die Another Day hit cinemas, the new Bond really needed to impress. Taking the casino motif of the entire film as inspiration, Daniel Kleinmann worked with VFX supervisor William Bartlett to create an artistic intro with combatants exploding into spades, diamonds and hearts, roulette wheels turning into targets, and Eva Green’s face being cleverly revealed in place of the Queen of Hearts; this credits scene goes to both foreshadow the film itself and set up the theme of gambling.

Cornell’s song itself mentions “the game that we have been playing” and the “spin of the wheel”, excellently combining with Kleinmann and Bartlett’s title sequence, and creating a genuinely watchable, entertaining opening credits sequence. The beautiful artwork tells a story itself, as 007 finds himself fighting through various grunts and mercenaries in his pursuit of Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd. Bond himself is symbolically represented by the Jack, indicating his underdog status and rivalry to the King, who is representative of the film’s antagonist La Chiffre, played by Mads Mikkelsen.

Therefore, Casino Royale is host to my personal favourite opening credits scene in cinema history.

Robb Sheppard – Se7en (1995)

The credit sequence to Se7en has long been ingrained on my mind; I was wily enough to sneak into an ‘18’ at a tender age, but too naïve to know that you don’t sit in the front row. It was and still is a visual and aural assault, whether you’re sitting too close to the screen or not.

Images flash by, only slightly lengthier than the subliminal: journals are scrawled into alongside photographs of malformed hands and head trauma patients, whilst medical papers on pregnancy and transsexual profiling are black-lighted. Flitting between haunted sepia and high contrast monochrome, the audience is taken somewhere between noir and horror, but unsure as to how it all fits together. What is for sure, though, are the connotations of a psyché that is both disjointed yet disciplined; precise yet perverse.

It’s on completing the film that we find that all the pieces matter. The killer’s hair clippers reference his off-the-shelf-psycho look, whilst his mutilated finger tips suggest he took garlic slicing inspiration from Goodfella’s Paulie Cicero. The onscreen credits implicate those involved as accomplices rather than collaborators; names appear to be scratched into the celluloid with a compass, whilst some are typed and smudged and retyped. Kevin Spacey as the pious John Doe of course, is fittingly and famously omitted.

The soundtrack doesn’t absolve the audience either. A barely recognizable reworking of Nine Inch Nails’ Closer is audibly dissected and rearranged, which is juxtaposed with the visual systemising of film strips, medical stills and ultrasounds. The murderous sonic subtext is also there for the initiated: Closer was recorded in the L.A. house in which Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family. Make out music, it is not. The only lyric permitted to seep through the noise is the climactic, “you bring me closer to God” which foreshadows not only the religious imagery of the seven deadly sins, Divine Comedy, and Paradise Lost, but of John Doe’s own lofty aspirations.

If you’ve yet to experience it, I’m truly envious.

Jay Ledbetter – The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

A good opening credits sequence should, first and foremost, prepare you for the next two-or-so hours of viewing. No sequence has done this better than that of David Fincher’s 2011 adaptation of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. It certainly helps that Fincher has such defined sensibilities that almost anything he puts out oozes pure, uncut Fincher goodness. The sequence is, basically, a strobing montage of intense imagery all coated in a thick layer of oil. Like the film that follows, darkness drips (here, the darkness and dripping are quite literal) from every inch of the events on screen.

It is interesting to note that these opening credits were not directly from the mind of Fincher, but Blur Studio, who were given broad parameters for how the director wanted the opening to feel but had a good degree of creative freedom to mold the breathtaking visuals that ended up in the final cut. Blur co-founder Tim Miller was quoted as saying Fincher wanted the sequence to “redefine titles for our generation the way Se7en did and that’s all there is to it.” It is safe to say they did just that, creating a bold short film that also works as a music video for the spectacular Karen O cover of Led Zeppelin’s Immigrant Song. We establish strong women from the get-go, making the transition to the non-traditional, punk rock, badass protagonist, Lisbeth Salander, completely seamless.

Any viewer could break the sequence down frame by frame and write a dissertation or they could simply let it wash over them like the gallons of oil on the character shown before them and they would leave equally satisfied. The sequences grabs you by the shoulders, shakes you violently, and lets you know that you are in for one twisted and mind-bending ride. The match will be lit. You will be set on fire. Are you ready?

Alex Lines – Battle Royale (2000)

Much like the explosive openings that welcomed every Russ Meyer film (the opening to Mondo Topless is the greatest thing ever done in cinema), Kinji Fukasaku knew how to open a film. Fukasaku was the key figure in transforming yakuza cinema from sparring samurais into modern day affairs of reckless gang wars. Fukasaku’s style leant well to the material, as he updated the traditional yakuza stories with young thugs brandishing knives and pistols, stuck in complicated affairs delivered with a pulsating energy, thanks to his use of colourful aesthetics, frantic camerawork and jazzy, upbeat soundtracks. Fukasaku’s films (especially his modern gangster films, such as Street Mobster, Graveyard of Honor and The Battle Without Honor or Humanity series) always opened with an immediate sense of intensity, conveyed through a rowdy musical cue, a string of crazy images highlighted in freeze frames and huge, bold title cards that instantly demand your attention.

This is no different in Battle Royale, Fukasaku’s final and highly controversial 2000 film, the movie which refigured the “Running Man” narrative for a new audience. Opening with the iconic Toho logo, Fukasaku establishes the film’s epic tone instantly with Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem Dies Irae, which is quite possibly the most epic orchestral song ever made. To match this, the film overlays this music with some basic title cards, with the striking Battle Royale logo slowly fading in.

What makes these opening credits so great is its instantaneous nature, and while it’s nothing fancy, it’s definitely effective. What helps maintain this awesome opening is the juxtaposition between the title cards and the film’s opening sequence, a manic series of images that hint at the world that we’re about to be introduced to, highlight the film’s frenzied tone and energy, and demands the audience’s attention in a manner that many exploitation films of the past did – give us a provocative or alarming image/scene so that the audience is on board with you right away. Giving the audience some bloodshed straight off the bat gives the filmmaker some time to world build and introduce exposition in the beginning without totally losing the audience’s attention, as these sequences can usually be the most boring in exploitation cinema (even though Battle Royale’s are not at all).

Dylan Walker – Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

The opening credits to Stanley Kubrick’s black comedy masterwork Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb have no plot purpose whatsoever. They are entirely inconsequential; it’s what they imply to the thematic elements of the film that make them so special. The credits appear over footage of two planes refueling in mid-air, set to romantic music and shot in a sensual manner, the scene could not be more overt in its implications. From the outset, Kubrick is letting the audience know that this film is going to be about sex.

This opening credit sequence masterfully sets up one of the film’s central themes: sexual inadequacy. From General Ripper launching a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union as he believes that Communists are poisoning the water supply with fluoride that hinders sexual performance because he failed to preform, to the constant association between war and pornography the film makes with its mise-en-scene. All of this is expertly set up by the opening sequence.

Kubrick even made note of it in response to a fan letter from Legrace G. Benson of the Department of History of Art at Cornell University: “Seriously, you are the first one who seems to have noticed the sexual framework from intromission (the planes going in) to the last spasm (Kong’s ride down and detonation at target).” This shows that the opening sequence of Dr Strangelove is not only one of the best, but one of the most essential.

Matthias van der Roest – Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Aguirre, Wrath of God opens with a scroll explaining the historical context of the story we are about to see. Although the scroll seems to suggest the film was based predominantly on the writings of the real life priest Gaspar de Carvajal, this is only partly true. The events in the film are a combination of events that took place during a number of expeditions mixed with fiction.

The film was loosely based on a real life expedition in search of the legendary city El Dorado, that included Don Lope de Aguirre (played by Klaus Kinski) and his daughter Florés (played by Cecilia Rivera), Don Pedro de Ursúa (played by Ruy Guerra) and his mistress Doña Inez (played by Helena Rojo) and Don Fernando (played by Peter Berling).

The opening scene of this film is great for a number of reasons. The establishing shot firmly cements the gorgeous yet unrelenting beauty of the landscape through which the expedition must struggle to get to El Dorado. At first we only see part of a mountain covered in smoke, but then the camera looks down at a group of people climbing down a mountain. After repeatedly zooming in, the camera arrives near the group, making it an invisible member of them, and now we start to see how difficult the climb is.

The music in this scene, by composer Popol Vuh, is important because it establishes the surreal nature of the film; the sound was accomplished by using pre-recorded tracks of choirs singing which were then played through keyboards, making it sound very otherworldly.

The interesting thing about this scene is that there is no dialogue at all, it’s just a brief voice-over and music, up until a canon is shown falling down the mountain and exploding. Even though there is no dialogue, the atmosphere of the film is clear, and you get the feeling this expedition has been cursed within 5 minutes.

Alistair Ryder – Enter the Void (2009)

Gaspar Noé’s fondness for hyper-stylization almost always works to his detriment; the reason Irreversible is one of the most detestable films of the century is because of his overbearing, try-hard transgression that aims to make racism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny and repugnant acts of violence against women as stylish and eye-catching as possible. It is undeniable that he has a great eye for innovative aesthetics – he just always channels them into his films in deplorable manners that appear to glorify the hell that is unfolding on screen.

Enter the Void, his third directorial feature from 2010, is business as usual for Noé; it seems to take delight in casual misogyny, as well as attempting to stylize humanity at its most horrific – he manages to joyously zoom through an aborted fetus at one stage. The film is overlong, meandering, and unbearably pretentious; indebted to 2001, yet leaving the viewer feel cold towards humanity rather than full of wonder. But for a brief moment, Enter the Void all but threatens to be Noé’s punchiest, coolest film to date – a work of style that doesn’t threaten to make you lose faith in mankind.

The film’s frenetic opening credits sequence, a genuinely mind-blowing amalgam of Japanese/English typography in all manner of different fonts, zooming by in a blitz of strobe effects, soundtrack by drones that eventually all burst into life thanks to the ADHD rave soundtrack courtesy of LFO. No single name stays on long enough to be deciphered (and there are plenty of names due to the assistance needed when creating the psychedelic special effects sequences here), and yet it leaves a lasting impression few opening credits sequences achieve. Most impressively, this sequence was almost never included; the producers were apparently worried that it would be hard to sell a three hour-plus film to foreign distributors, so Noé put all the titles right at the start, in the quickest manner possible. It was a work of style that finally paid off.

What are your favorite opening credits? Let us know in the comments!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover. He's perfecting his cat dad energy.