Staff Inquiry: Our Favorite Adaptations

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover.…

It’s a doozy for this month’s staff inquiry as the team selected their favorite adaptations of books, short stories, comics, plays, and other preexisting narratives. Considering that cinema has been pulling from other formats throughout its history, the possibilities were endless. There’s lovingly faithful adaptations and those that play fast and loose with the original idea. There’s also movies that introduced us to great stories and others that strengthened our appreciation of old favorites.

Even when we figured out what we personally love in adaptations, we were still left with a huge list of films to cull from. Each person who accepted the challenge selected ten and named one as their personal favorite, and while a few common threads appeared (we love Kubrick), you’ll find that we have wide-ranging ideas on what makes an adaptation great.

Alice Murray: The Help (2011)

As well as being arguably one of the most inspirational stories in film and book history, I feel like The Help embodies a huge variety of elements and entwines them so perfectly. It is full to the brim with passionate, strong-minded and influential characters; the majority of whom are women. The film itself portrays different outlooks from each character’s perspective and allows the audience a real and raw insight into their lives. Not only that, but it uncovers a prominent piece of history; one where female slaves of colour could fight for their rights and put it onto pen and paper for the entire world to see.

Although it is a work of fiction, it pushes boundaries by interlinking strong women from different backgrounds, compelling even the most on-the-fence thinkers to strike up their own opinions and beliefs. It’s alive with emotion and humour equally whilst managing to express such a poignant and moving narrative.

I think my own personal reasoning for feeling so attached to this adaptation is the connection I feel to Emma Stone’s character Eugenia ‘Skeeter’ Phelan. She is a zealous writer who aims to change the world with her words, and the book is an incredible interpretation of the idea that writing can make a massive difference.

Although I’m guilty of having read the book only once, I have watched the movie a hundred times over and will continue to do so. To me, it demonstrates a gracious tribute to women, writers, slavery and black history; it’s simply perfect.

The rest of Alice’s top ten: Eat Pray Love, Argo, Shutter Island, Harry Potter (series), Hacksaw Ridge, The Imitation Game, The Notebook (2004), The Pianist (2002), Gone Girl

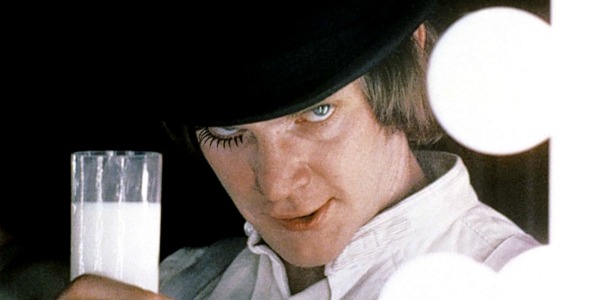

Alistair Ryder: A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Although he will forever be remembered as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, the key to Stanley Kubrick’s genius is disarmingly simple. He was a master of adaptation, who understood the difference between what made a great work of literature, and how the strengths of the written word may not be the strengths when translated to screen. Some authors may not have been particularly delighted with how he interpreted the stories for a different art form (hello, Stephen King!), as he often obsessed over certain themes and imagery that were merely a footnote in the source material.

With A Clockwork Orange, his 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel, Kubrick made the most faithful adaptation in his entire career, even if it did omit the denouement of Burgess’ source material (which was blamed by Burgess not on Kubrick but by the US publisher inexplicably failing to include it). This faithfulness to the source material can be accredited to two reasons.

Firstly, Burgess’ otherworldly prose sounds utterly irresistible when read out loud, with Malcolm McDowell chewing up and spitting out every line of Nadsat dialogue (a Russian-influenced slang that led viewers at the time to see this as a vision of communist authoritarianism) like it was a Shakespearean sonnet. The second reason is that at times during filming, Kubrick reportedly discarded his adapted screenplay in order to just open the book and film a scene depicting whatever was dictated on any given page.

This led to the most dialogue driven film of Kubrick’s career, give or take a Dr Strangelove, leaving the intrinsically detailed world Burgess created to gestate in the background. For a director often described as cold, adapting the film this way ensured that the challenging themes and characterisations were put at the forefront, as opposed to his artful stylistic ticks- a rare case in Kubrick’s career where even the few detractors will find it hard to argue that he didn’t prioritise substance over style.

The rest of Alistair’s top ten: Fight Club, The Graduate, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Oldboy, Let the Right One In, There Will Be Blood, Trainspotting, Stand by Me, Apocalypse Now

Amanda Mazzillo: They Live (1988)

John Carpenter’s They Live might not be the first film to come to mind when you think of great film adaptations, but it stands out as one of my favorites. It is based on the short story Eight O’Clock In the Morning by Ray Faraday Nelson. The story is very short, yet packed with emotional imagery and political satire, which has been relevant since the story was first written in 1963 all the way to when They Live was released in 1988 and remains just as relevant today.

While the character in the short story is awakened by a hypnotist and the rest of the subjects remain blind to their reptilian leaders, the character in the film discovers a pair of sunglasses which allow him to see the leaders as what they truly are. This change from the short story allows the film to go in different directions.

The tone of the film is one of my favorite aspects of They Live, especially its mixture of the comedy, horror, and action genres. Roddy Piper and Keith David falling into a twelve minute fight scene all about the refusal to put on a pair of sunglasses sets the tone for this wonderful film filled with lines as classic as “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass… and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

They Live works well as a social satire with its subliminal messages coming from these hidden leaders telling us to never question their authority, throw away independent thought, and value money above all else. These types of messages are peppered throughout the short story as well, letting it quickly create a horrific yet all too real view of our world.

The rest of Amanda’s top ten: Paper Moon, Bridget Jones’s Diary, The Player (1992), The Heartbreak Kid (1972), Dick Tracy (1990), The Diary of a Teenage Girl, Josie and the Pussycats, Freaks, The Graduate

Benjamin Wang: Whisper of the Heart (1995)

Whisper of the Heart is a simple movie that sums itself up quite neatly in one of its fantasy sequences: things close-up appear small, things far away appear large. When you approach something new, you’re approaching minutiae of stories, systems, and people.

It’s the adaptation of a comic but for the most part develops its own visual parlance, the most important part of which is its breathtaking devotion to cluttered spaces. All over the movie you can see little things that hint at unseen pasts of human ambitions, successes, failures, responsibilities, and relationships. We see a city both in its totality as a distant landscape in the background and its myriad bits and pieces up close when the main character walks through it.

Whisper of the Heart doesn’t shy away from loss, nor does it ignore the difficulty of moving past the familiar. Even so, it suggests that what you might find there is more than worth it. Maybe that sounds like a platitude, but it comes across so powerfully in this film’s form that I was convinced – in fact, there is no movie that materially affected my conduct the way Whisper of the Heart did.

At one point in the film, an elderly friend of the main character shows her a geode; he encourages her to find the gemstone within herself and do what she can to polish it. Whisper of the Heart embodies the spirit of this sentiment: it contains little flashes of genius, and to the viewers who extract them, it offers boundless potential.

The rest of Benjamin’s top ten: Ordet (1955), Blade Runner, The Shining, Manhunter, Black Girl (1966), Ghost in the Shell (1995), The Trial (1962), The Long Goodbye, Throne of Blood

Chris Watt: All The President’s Men (1976)

There is a moment in All the President’s Men when a character says “I don’t mind what you did. I mind how you did it.” It’s a moment in which the dynamic of our two main characters are established, but it’s also a hefty warning as to the perils of book to screen adaptation in general.

Scripted by William Goldman from the incendiary book by journalists Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, his work here is quite simply a master class in adaptation. Nixon era politics, Watergate, the inevitable shoe leather approach of the story’s two protagonists, not to mention a narrative with no discernible villain outside of the constantly glimpsed on TV Nixon, Goldman wrings every ounce of drama and tension out of one of the greatest examples of teamwork ever committed to paper, never mind celluloid. By never taking focus off of Woodward and Bernstein, played onscreen, respectively, by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, the screenplay weaves a claustrophobic yet utterly compelling look at just how such an investigation can come to pass.

From fights with editors, paranoia over wire taps, the remarkable power of finding a witness who will actually go on the record, Goldman is giving us a procedural, a close up look at fingers typing, of ears pressed to phones, the bustle of the Washington Post’s newsroom and of a government on the run, desperate to stop the two men who are capable of bringing it down. There is no grandstanding, no epic speeches, and Woodward and Bernstein share almost exactly the same amount of screen time. It’s deliberate of course, Goldman being a writer completely in control of what he knows is one of the most important stories of his generation.

You won’t mind what he did. And you’ll love how he did it.

The rest of Chris’s top ten: The English Patient, Sense and Sensibility, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Adaptation, Wuthering Heights (2011), Under the Skin (2013), The Princess Bride, The Age of Innocence (1993), Trainspotting

Emily Wheeler: All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

After being decimated by World War I and the flu pandemic, many members of the so-called Lost Generation struggled to reconcile the horrors of their past with the mundane life before them. A cultural divide formed between those who had survived the front lines and those who had been spared the trauma, and while that gap could never be fully crossed, many pieces of art tried to fill it in as much as possible.

One of these came from German veteran Erich Maria Remarque, whose novel All Quiet on the Western Front gave readers a taste of what a World War I soldier had endured. It spread like wildfire around the globe and a film version was released in 1930. By incorporating sound (still in its infancy) and lifting from the book a dogged, harrowing depiction of war, All Quiet on the Western Front is still upsetting and moving to this day.

Remembered as one of the great anti-war films, its power comes not from grand statements or impassioned pleas but from the empathy it stirs for all soldiers, no matter the side. As its written prologue eludes to, the film is an attempt to explain how war destroys even the survivors, and it wholeheartedly succeeds.

The rest of Emily’s top ten: Million Dollar Baby, Jaws, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, The Bridge on the River Kwai, Trainspotting, Persepolis, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Planet of the Apes (1968), Touching the Void

Jacqui Griffin: To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

I saw To Kill a Mockingbird in the seventh grade, immediately after finishing the novel by the late Harper Lee. For some background, I grew up in a medium-sized Pennsylvania town in an almost exclusively Catholic community – racism was not much of a concern for us. The book impacted in a way nothing had before and few novels have since, as it showed me, so clearly, another side of life.

What I’m trying to say is that the stakes were set extremely high for the film, and despite that, I don’t think there is a more perfect adaptation in all of cinema history. Much of this is due to the unbelievably powerful performance by Gregory Peck, who quickly became one of my first proper Hollywood crushes. You’ll be hard pressed to find a more poignant, tragic, beautiful, and moving film, and though it’s not my favourite film ever (see number 5), it is far and away the best adaptation to film from another medium (in my humble opinion).

The rest of Jacqui’s top ten: V for Vendetta, Adaptation, The Maltese Falcon, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worry and Love the Bomb, Sense and Sensibility, The Graduate, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, About a Boy, Sin City

Linsey Satterthwaite: The Virgin Suicides (1999)

Sofia Coppola is a director who often favours mood over narrative; she creates a feeling within the frame, allowing her characters to exist rather than be bounced from one plot line to another. And never more so has she created a sensory experience so well than with her debut film The Virgin Suicides, an adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel of the same name.

The story, set in 1970s America, about the lives of the doomed Lisbon sisters is the perfect fit for Coppola’s style and is one of the most faithful adaptations I have seen. Coppola creates a dreamy, hazy c*cktail of images, filled with the hints of the melancholy that will engulf the teenage girls and the threat of tragedy that will befall the family. Aided by France’s purveyors of pop malaise Air and their swooning score, Coppola takes us on a journey through a long hot summer that is always tittering on the edge of having its captivating bubble burst.

Since watching Coppola’s film I have reread the book and I felt that my sense had been heightened, that I could smell the grass where the Lisbon girls had laid and could feel the sunlight on my lids that had touched their skin before their enforced housebound exile. I don’t feel that the film clouded my vision of the book; it simply enhanced the mood of the story that was already there. Coppola had taken the essence of The Virgin Suicides and planted it into my subconscious, distilling a heady concoction of wistful summer days and the pleasure and the pain of adolescence. As the sun goes down, the book ends and the film draws to a close, so many questions are left unanswered yet so many feelings have been conjured that render the need for words.

The rest of Linsey’s top ten: Fantastic Mr. Fox, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Carol, American Psycho, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Life of Pi, Room, Gone Girl

Matthias van der Roest: They Live (1988)

John Carpenter’s 1988 science fiction masterpiece They Live was based on the 1963 short story Eight O’Clock in the Morning by Ray Nelson which can be heard, as read by legendary sci-fi short story narrator Gregg Margarite, here. They Live tells the story of a great conspiracy being perpetrated against the American people by an unholy alliance of foreigners and their American collaborators.

They Live takes place in a world not so different from ours and as such it is a brilliant piece of social commentary on 1980s Reagan era greed, or corporate greed in general, in the same way a movie like Oliver Stone’s Wall Street is.

They Live stars professional wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper as the drifter John Nada. Nada gets a construction job and meets Frank Armitage (Keith David) who decides to help him out. Things start to unravel once Nada finds a box of sunglasses in a local church. Once he starts wearing the sunglasses he notices something strange, they seem to change his view of reality. When he wears them everything is black and white and all commercial statements on billboards and magazine covers are unveiled as messages of propaganda urging people to ‘consume, obey, stay asleep, and work.’

Once Nada realizes what’s truly going on he starts to try and rally people around him to take action against the conspirators which results in one of the most fun fight scenes in cinema between Nada and Armitage. In a way this scene is symbolic for how painful it can be to change your way of thinking.

The rest of Matthias’s top ten: Blade Runner, Chopper, Christ Stopped at Eboli, The General, In Cold Blood, The Lord of the Rings (series), Once Were Warriors, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Wake in Fright

Nathan Osborne: Gone Girl (2014)

Gone Girl had an almost insurmountable task ahead of itself. Based on Gillian Flynn’s best-selling novel, the 20th Cenutry Fox release needed to handle an unreliable narrator, mercurial characters and timelines that frequently overlapped, chopped and changed path. In the wrong hands, it could have been an unmitigated disaster; however, in hiring David Fincher to take up the directorial reigns, and Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike as the two lively leads, they created something rather perfect.

With a firm grasp on the twists and turns that made Gone Girl the book so thrilling and the gender themes that made it such a pop culture phenomenon, Gone Girl the film fired on numerous cylinders and succeeded on them all. The Oscar-nominated film (which deserved so much more than the single nod for Pike’s flawless portrayal of Amy Elliot-Dunne) is a masterclass in book-to-screen translation – and one that many could, and should, learn from. From class performances of Affleck and Pike to the reliably arresting direction from Mr. Fincher, as well as the superb production values, cinematography and score that completes the extraordinary package, Gone Girl is the pinnacle of book-to-film adaptations.

The rest of Nathan’s top ten: The Hunger Games (series), Arrival, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, A Monster Calls, Harry Potter (series), Room, Hidden Figures, The Help, The Girl on the Train

Stephanie Archer: The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

Young adult adaptations carry a stigma – they are typically either decent, yet no one goes to see them (Beautiful Creatures, Shadowhunters: The Mortal Instruments) or they are acceptable attempts, the quality of the film just good enough to satisfy fans (Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, Divergent). Sequels for young adult adaptations are viewed as being even worse (Twilight and Divergent series), with filmmakers and studios banking on a loyal fan base to carry ticket sales instead of maintaining or improving on the quality of the original film. This, however, was not the case in the making of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.

As a fan of the franchise, I personally loved the first installment of The Hunger Games, yet when I look at the film through a critical eye, there was much left to be desired. The story was honored, its characters brilliantly represented by their cast, yet there was so much more that could have been given to the quality of the film. With the second installment, I was excited to see the next book brought to life (a loyal fan bringing in tickets sales), as well as intrigued to see what Francis Lawrence, the film’s new director, would bring to the franchise.

The first thing I remember was the color – so vibrant, so hypnotizing. Permanently ingrained in my mind is the final scenes of the film after Katniss (Jennifer Lawrence) had broken through the ceiling of the arena – the color, the sound, the slowing of the scene as debris falls explosively around her- perfection. It was the epic conclusion, beautifully captured on film, perfectly showcased on an IMAX screen, breathtakingly and solidly concluding the second chapter.

The second thing was how grown up the film presented itself. This was no longer a young adult film, but a film for all ages. From start to finish, Catching Fire was sharp and sleek, from script to direction to cast – every element heightening a love for film and a love for the text. Through its showcase, I can truly say Catching Fire is one of the few young adult adaptations where a love for the franchise, its story, and its characters pours through every element and every heartbeat of the film.

This film was of such caliber, it is a testament to the level of filmmaking young adult adaptations can reach and the true expectations we should have for them – no matter the extent of their fan base. Following this film, my expectations for young adult adaptations has been drastically risen, my demand for higher quality filmmaking at a new level. With the announcement of new literature being adapted, especially of the young adult nature (The Selection series), I hope the filmmakers-to-come take note from the success of this film and that the “odds may ever be in their favor”.

The rest of Stephanie’s top ten: The Fault in Our Stars, The Princess Bride, Gone Girl, To Kill a Mockingbird, Beasts of No Nation, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Where the Heart Is, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

Zachary Doiron: The Shining (1980)

Can anybody really beat Stanley Kubrick? His boldness of changing the beloved book on which The Shining is based showed confidence and craftsmanship from his part. His different approach from Stephen King’s novel should be an example for any director wanting to adapt a novel. He wasn’t afraid to change certain aspects of the novel to fit his vision. People who had read the book not only didn’t know what was going to happen but had a different experience.

We often find debates on which is better, the book or the movie? With The Shining, both can co-exist without there being one that overshadows the other. Of course, no one can really make something better than Stephen King. His novels are often horror masterpieces and a lot of his movie adaption have been overshadowed by his books. Kubrick was smarter than that. He didn’t want that to happen and in the process, proved to everyone that novel adaptions can still be artful filmmaking. By changing certain aspects, he was able to create his own masterpiece that would transcend time and become one of the best movie of all times.

The rest of Zachary’s top ten: Psycho, Gone Girl, X-Men: Days of Future Past, Misery, Room, Mystic River, A Clockwork Orange, We Need to Talk About Kevin, Edge of Tomorrow

That’s all of our favorite adaptations. What are yours?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alex is a film addict, TV aficionado, and book lover. He's perfecting his cat dad energy.