It’s a well-known rule that the book is better than the film, perhaps because it had more space to tell its story, more time in the audience’s head, or simply that it made the first impression. It’s often the version people fell in love with, and a substitute rarely satisfies.

Except, of course, when it does. Movies have been pulling from books, short stories, plays, and a plethora of other media throughout its existence, and by simple probability, some were bound to end up better than their source. This month, our staff is digging into our favorite examples of films that exceed their written source, and we’ve come up with plenty of reasons why these oddities happen.

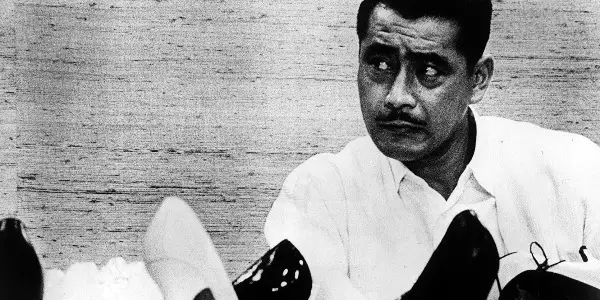

Tynan Yanaga – High and Low (1963)

I was drawn to pick a film that so unquestionably transcends its source material that there’s no room for dispute of any kind. The exemplars that spring to mind include classics where people forget their sources, like a stylized film noir from 1946 based on Hemingway’s The Killers, or, on the other end of the spectrum, mega blockbusters that easily overshadowed their origins. Take Jaws, for instance.

However, an equally compelling entry is Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, a thriller turned police procedural that actually was loosely adapted from Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom, part of his ongoing 87th Precinct Mystery series. Consequently, McBain would pen the script for Alfred Hitchc*ck’s The Birds, but let’s consider Kurosawa’s work.

Like many of the best cinematic adaptations, it’s not a mere faithful transposition of ideas, but it takes the root of a story and builds it into something formidable in its own right. With his constant muse Toshiro Mifune giving another dynamic performance as ruthless businessman Gondo, Kurosawa toys with a plethora of moral issues. The most substantial stems from the fact that though Gondo initially believes his son is kidnapped, he is faced with the dilemma of sinking his entire fortune to save someone else’s child.

After the dragnet closes in and Gondo is ultimately faced with the man who all but succeeded in ruining him, he realizes there’s no sense of remorse in this condemned face staring back at him. As Gondo is brought low in his avarice, we are reminded of the vices that drive man. Despite the polarity in this title and the main characters, there’s also a disarming realization that they are both shades of muddied gray. No one is perfect – not even one.

Andrew Winter – You Were Never Really Here (2018)

There’s not much wrong with Jonathan Ames’ original novella of the same name from 2013. Short and sharp, his all-action tale told the story of Joe, a former soldier and FBI agent turned hired muscle who specialises in finding young women trafficked into prostitution. He is a brutal man who has suffered a brutal life, first at the hands of an abusive father and later in various theatres of conflict.

The book isn’t even a hundred pages, but when writer/director Lynne Ramsay (We Need To Talk About Kevin) decided to adapt it for the screen, she opted to throw out a lot of the backstory and detail – all carefully laid out by Ames – and instead concentrate on the consequences a lifetime of violence has had on Joe’s psyche. She was interested in exploring what it was like to actually spend time in his head. And whilst her film is, as Edgar Wright called it, a “revenge movie as tone poem”, it is also very much a character study of a man punch-drunk from PTSD who suffers nightmarish flashbacks and thinks of killing himself on a daily basis.

In the movie adaptation Joe is played by Joaquin Phoenix, who cuts an altogether less macho, more sympathetic figure than Ames’ cookie-cutter tough-guy protagonist does. They both dish out blunt-force justice with a ball-peen hammer, but Ramsay has little interest in action scenes. Most of the violence in her film either takes place from a distance or on grainy CCTV. She doesn’t want to make a variation on a Jack Reacher film, which would have almost certainly been the case had some other director got hold of Ames’ book first.

The Scottish filmmaker even punches up the writer’s finale – open ended and unsatisfying in the book, disturbing, strange but a little more hopeful in her adaptation.

Kristy Strouse – The Godfather (1972)

As a book fan, at first I thought it would be difficult to find a film that improved upon its source material. However, the more I pondered the more options came to mind.

Normally, the book is preferred because it’s expansive and a lot has to be left out once it’s adapted. It’s more intimate, and as a reader, you create this world in your mind, and sometimes when you see it on screen you’re disappointed.

I decided to go with The Godfather. First, it’s necessary to say that Mario Puzo’s book is an excellent piece of literature, but how can I not talk about the film (and subsequent sequels) that it spawned when the first especially is one of my favorites of all time? The second reason is because it’s so damn easy to talk about. How much time do I have?

I believe it goes without saying that The Godfather is a classic, and it’s an achievement in filmmaking.

The film by Francis Ford Coppola is eternal; it doesn’t feel dated. I still get chills from the music and from the iconic scenes (the restaurant assassination, the christening in particular) and especially the performances. Marlon Brando steals every scene he’s in.

Michael Corleone is one of the greatest characters to ever fill the page or screen, but Al Pacino transforms him from a concept into a full fledged, warm blooded force of nature. Some will argue the second film is better, and I understand the logic, but the first will always have a special place in film for me. His transition from the good son, hero, to a hardened monster by the end “This one time I’ll let you ask me about my affairs” is one of the best. Pacino does it with such an ease that it’s…mwah, perfecto.

Matthew Singleton – Drive (2011)

Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2011 film Drive is very loosely based on the book of the same name by James Sallis. Both tell the story of a driver who works as a stuntman but moonlights as a getaway driver for criminals. Sallis has a back catalogue of excellent work and Drive is no different. The novel is a lean, sparse slice of noir fiction, brilliant in its own way. However, whilst the minimalist style works well for Sallis, it is just incredible in Winding Refn’s hands.

Winding Refn has more to play with on the big screen in order to create a masterpiece. He has the muted yet powerful performance of Ryan Gosling as the unnamed Driver and the superb talents of Carey Mulligan, Oscar Isaac, Bryan Cranston, Ron Perlman AND Albert Brooks. He has the unbeatable soundtrack and score of Cliff Martinez, which genuinely pushes the film into modern classic territory. The importance of the music’s contribution to the film cannot be understated, as this blends perfectly with the neon-drenched visual style of Winding Refn and DP Newton Thomas Sigel.

James Sallis’ book is fantastic, there is no doubting that, but it just doesn’t come close to Winding Refn’s film.

Linsey Satterthwaite – Gone Girl (2014)

I was a fan of Gillian Flynn’s third novel Gone Girl, which was a fantastic postmodern slice of shadowy charades within the suburbs. It may seem superfluous to call the film better than the book when Flynn handled the screenplay adaptation herself, but under David Fincher’s direction, Gone Girl was elevated from the best page turner of 2012 to one of the best thrillers of the last decade.

It’s hard to think of a better fit for Flynn’s source novel than Fincher; a mercurial, multi-layered mystery with duplicitous characters is prime fodder for his auteur palette. Fincher’s whip smart and precise direction conveys every detail you need yet still leaves you on the edge of each frame, even if you know how this twisted story ends. He is never afraid to go to the darkest corners of the human psyche and hold this up for the audience to see.

He steers his ship with such expert craftsmanship, aided by a stellar cast, that the parts of the narrative that may have felt excessive on the page seem entirely plausible and chilling on the screen. In one particular scene a flash of violence is done with such cold, calculated efficiency that it leaves you stunned but is sold with matter of fact conviction by Rosamund Pike. She brings Amy Dunn to life perfectly, her icy exterior impossible to penetrate but also impossible to take your eyes away from, while Ben Affleck sums up his character Nick’s foolish nature in one beautifully mistimed, misplaced smile.

Since Gone Girl’s publication there has been a boom in female-led thriller novels, but Flynn’s entry still stands out as the best example of the genre, bolstered by Fincher’s superior film version, whose wickedly callous style haunts long after all the pages have been turned.

Matthew Roe – Requiem for a Dream (2000)

By his own admission, author Hubert Selby, Jr. said of his novel Requiem for a Dream that it “started as a joke”, a dark comedy about a couple strung-out junkies. Selby had battled with his own drug addiction until roughly 1967, after which he remained sober until his death in 2004. This novel, which took six weeks to write and edit, centers on four New Yorkers who gradually capitulate to their addictions at the cost of their health, community, industry, and self-worth.

Infamously renowned for his freeform style and controversially seedy subject matter, Selby often blended the gritty elements of (then) contemporary underworld life with the experimentation of William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. Though this novel of late-1970s American literature is utterly distinctive, I find its 2001 film adaptation by Darren Aronofsky not only more digestible than the source but also one of the great modern masterpieces of American cinema.

The novel acts as a snapshot of 1970’s New York junkie culture, primarily told through an unfiltered stream-of-consciousness from the protagonists; all thoughts and actions blend together into a tornado of chaos and sickness, and truthfully if you want the full picture of each character, then the book is where to go. Though many sections of the book are directly lifted onto the screen, the film (which Aronofsky co-wrote with Selby) trims a lot of unnecessary mental fat off the story, steering the chaos to take a distinctive stance different from its source: the true main character is addiction.

Much like in Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly (which has its own amazing film adaptation directed by Richard Linklater), deconstructions of addiction’s effects are better told through a series of masterfully constructed visualizations than a fever dream of scatterbrained narration. While the novel remains a significant work, the film makes the subject timeless, more viscerally brutal, and even more sickly relatable.

Nathan Osborne – Arrival (2016)

Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a bad piece of literature; its endless accolades and acclaim are a testament to that, and the startling way it explores language and determinism is so profound and powerful, unlike anything I’ve encounter before in this form. I would recommend it to everyone in a heartbeat, an appropriately sophisticated piece of prose that you will struggle to forget.

But Denis Villeneuve’s film adaptation, renamed Arrival, develops emotion not nearly as pronounced in the novella — and the story benefits all the more from it. While it still maintains the level of science and semantics crucial to the narrative and its themes, it’s slightly less clinical in its execution of these elements while also delivering a touch more clarity to some of the more complex facets of the story.

It’s an impossible task to ask, really, requiring Villeneuve and screenplay writer Eric Heisserer to structure a sequence of events every bit as fluid as the movement of the film’s aliens for a mainstream audience – and the pair absolutely nail it. With such confidence and conviction, they craft a film that works far better than it had any right to, so well balanced and with such remarkable power and influence. Bolstered by Amy Adams’ astonishing performance, few films have impacted me as profoundly as Arrival has and always will. It really is a modern masterpiece that will go down in film history.

Amanda Mazzillo – American Psycho (2000)

When thinking about films that are better than the book my mind went to a few different places, but I finally landed on American Psycho. I know some audiences watching a film based on a book want to see everything depicted on screen, but this is never realistic. I think American Psycho did a wonderful job of picking the right moments from the book to highlight.

When reading the novel, I felt there was almost too much detail in certain scenes. Director and co-writer Mary Harron managed to capture the tone of the book through the visual medium of film. The satire of 1980s yuppie culture comes across well without every scene having full commentary about what a character is wearing and eating. The film is really good at choosing when this type of commentary will benefit the film, making these moments both more funny and more introspective of the characters than they were when I read the book.

The film does a really wonderful job of showing how every character is so caught up in their own lives that they don’t notice what is going on around them. American Psycho is one of my favorite adaptations because not everything is exactly like the book, but the limitations of how much content you can include actually works to make the film more engaging. Harron managed to craft a film which looks more deeply into the self-focused nature of its characters, capturing the satire in a crisper way than the novel.

Becky Kukla – The Virgin Suicides (1999)

When a universally heralded book is adapted into a critically acclaimed film, it’s generally viewed as a win for both sides. The Virgin Suicides is one of these rarities which seems to work just as well onscreen as it does on the page – yet there are a few notable differences from Eugenides’ original novel to Sofia Coppola’s debut feature film.

One difference, which undoubtedly has the most impact, is which story Eugenides and Coppola have decided to tell their audience. For Eugenides, the story belongs to the narrators – the young neighborhood boys who watch the Lisbon sisters from across streets, in school classrooms, and ride with them in the back of cars. For Coppola, the narrative focuses on the girls themselves, with the neighbourhood boys become more of a footnote in the story of sisters’ complicated lives.

Though Coppola’s film is still predominantly narrated by the boys (through a singular character), the audience are privy to information about the girls’ lives that in Eugenides’ book were often considered either rumours or second-hand information. In Coppola’s film, we are invited further into the home and inner lives of the Lisbon girls in a way that the book never lets us.

Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides exudes a dreamlike, hazy quality which is vaguely hinted at in the original text, mixed with fast-paced, quirky editing incorporating popular music and hand-drawn, childish graphics. The film bounces from slow and existential to a more typical teen-girl chick flick effortlessly, reminding us that these girls aren’t the heavenly and exotic creatures that the male narrators believe them to be. They’re actually young girls reaching a pivotal moment in their lives, trapped in a toxic household, desperate to become adults.

Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides works in a different way to Coppola’s film, and for me Coppola’s version allows for a deeper and more interesting identification with the tragic figures of the Lisbon characters. There is understanding, rather than an idolisation, which Coppola navigates beautifully.

David Fontana – Lord of the Rings

In thinking about my favorite adaptation that was better than its source material, there were a few to choose from. Yet, in the end I went with my favorite all-around series, The Lord of the Rings. Now before you place me in the category of BLASPHEMY, let me explain: I enjoy J.R.R. Tolkien’s novels, from the Lord of the Rings series to one of my favorite children’s novels, The Hobbit. But while I adore Tolkien’s words, I endear Peter Jackson’s vision of them (The Hobbit films excluded).

I first read Tolkien’s novels when I was around 10 years old, when books were (and still are) one of my favorite outlets. I’d often be found with my nose buried in a novel, finding solace through the exquisite worlds created by writers. But while I had fun reading Tolkien’s novels, I often found that his writing style was sometimes too long-winded for my taste. In some cases, he would take several pages to describe a single setting, or in others, entire subplots seemingly served little purpose (Tom Bombadil, for example). It took me admittedly longer to read each of the Lord of the Rings books than it normally would have as a result. Rereading the novels later in life helped me to get past some of these issues, but I still was never fully in love with them as I have been with other series.

Fast forward to 2001. As a 13-year-old boy, I hadn’t yet experienced much of cinema outside of the latest Disney offering. Yet, I still remember my first experience in the theater watching Fellowship of the Ring. I loved seeing Gandalf brought to life by the gruff, deep-voiced Ian McKellan, or the enraptured performance of Viggo Mortensen as Aragorn, or the doey-eyed Elijah Wood as Frodo. Seeing Middle Earth presented through the vast landscapes of New Zealand was breathtaking, while Howard Shore’s iconic musical motifs perfectly encapsulated Tolkien’s many settings and creations. The action scenes were epic and full of energy, and like nothing I had ever seen before. Not long after my first watch, I begged my parents to go see the film again in theaters, and in late 2002 and 2003, you can bet I was there for the next two in the series.

It is from seeing Fellowship of the Ring that I can truly trace back my love for film, experiencing for the first time its boundless potential. I have since rewatched all three films countless times (special editions or bust), and I will likely never tire of them. So while I still admire Tolkien‘s novels (and wish they weren’t making yet another adaptation of them, but that’s a debate for another day), I wouldn’t be the same person today without Peter Jackson‘s The Lord of the Rings.

Mark Farnsworth – Excalibur (1981)

John Boorman’s Excalibur is a glorious ode to the Arthurian legends. Visually violent, opulent, and flooded with Shakespearean talent, Excalibur’s beating heart literally pulsates and bursts out of the screen, beating a bloody path across the soul of anyone lucky enough to experience it. The source material is Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, the high watermark of fifteenth century English verse and prose, a worthy pursuit in itself which is elevated to the gods by Boorman’s cinematic bravura. Whether using Wagner’s Funeral March from Gotterdämmerung to reveal Merlin and Uther Pendragon’s doomed union or blazing O Fortuna by Carl Orff across Arthur’s final battle, Boorman holds Malory’s book completely under his sway.

The dialogue is preposterous and portentous, thundering through our very being. Witness Lancelot, bearded and disgraced, riding into war with his King for the last time and then cradled by Arthur, dying in his arms. Surrounded by glittering corpses and a blood red sun, they survey the death of the old world and the emergence of Christianity. “My salvation is to die a Knight of the Round Table” Lancelot exclaims seeking redemption. Arthur looks upon him with chivalric devotion, “You are that. And much more. You are its greatest Knight. You are what is best in men.”

Excalibur is what is best in movies.

Zoe Crombie – The Shining (1980)

Fans of Stanley Kubrick and Stephen King alike are well aware of the debates surrounding whether the former’s adaption of The Shining is better than the latter’s original novel. Personally, despite being a fan of each, I would argue that the visual element provided by Kubrick’s meticulous direction has made the concept of The Shining as significant as it is within both popular culture and the minds of critics.

Whilst the novel provided an excellent premise and setting for the film, much of what makes Kubrick’s adaption arguably one of the greatest horror movies ever made is not present in King’s book. The iconic hedge maze where a crazed, axe-wielding Jack Nicholson chases down his young son is a new addition, along with the ambiguity that surrounds whether Jack Torrance was made insane by the oppressive Overlook Hotel or whether he was always inclined towards violence. There are also concepts that deliver effective scares purely on a visual level, such as the elevator filled with blood and the typewriter containing the now iconic phrase ‘all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’.

Even aspects of the book that are present in the film feel more vibrant and effective purely by the virtue of being in an audio-visual medium; concepts like the Grady twins and the grand yet claustrophobic nature of the hotel itself feel made for the screen. The discordant synth score combined with the abrupt editing give a strange sense of the passing of time onscreen and enhance the dysfunctional family dynamics and sense of supernatural mystery from the original.

All in all, I find the cinematic adaption to be a far more visceral experience, creating an atmosphere that the book can’t quite match.

Stephanie Archer – The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

Widely known by audiences, books rarely translate to film – leaving fans disappointed and bewildered by how the screenwriter and director had failed their beloved text. Yet, while there are many that have failed to live up to a predetermined standard, there are a few gems that stand above the rest. The Hunger Games: Catching Fire is one of them.

What made this film stand out for me among the rarities of book adaptations is that Catching Fire is also a sequel. As many know, sequels alone have difficulty reaching the level of the original. When The Hunger Games was released, it was a good YA film, yet was by no means what fans had hoped for. As the release date for Catching Fire approached, my heart sank with the knowledge that it could turn out worse than the first film – heartbreaking as this had been my favorite book in the trilogy.

Color me shocked when I walked out of the theater speechless, loving the film more than I had loved the book. There were so many creative decisions that drove the movie to a higher level. The book alone was brilliant, yet the film had not just followed what was written on the page but also incorporated the meanings between the lines.

New scenes were added to enhance the courage and motives of characters. Heavensbee, who is in the beginning and the end of the book, has more screen time, showing the fight and protection he provided for Katniss. Scenes were also removed, like Katniss injuring herself climbing the fence in District 12, allowing more time for other scenes to fully develop and mature as well as allowing more of the film to unfold within the arena.

Characters are also given greater depth and meaning. Gale is whipped for defiance and saving a woman from a peacekeeper instead of punished for hunting. He becomes more of a hero, giving further credibility to his character and his choices as the series progresses into further sequels. Through the addition of a granddaughter, President Snow is also given greater depth of character. Whereas he was a straight on villain, hungry for power and control, the addition of a granddaughter gives his character a deeper psychology: jealousy, longing. His granddaughter wants to be like Katniss and not him.

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire is one of the top book-to-screen adaptations out there and an overall favorite of mine. Through brilliant decisions and further character development, Catching Fire was able to lift itself above the text from Suzanne Collins and become a stunning display of film perfection on screen.

Those are just some of the films that exceeded their source material. Which do you think are better the book?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.