The popular myth of German architect Albert Speer as “The Good Nazi” was made apparent to me in college. He was a man who had the ear and the trust of one of the great tyrants of history: Adolf Hitler. And yet when many of the others met their demise including Himmler, Goebbels, and Goering, Speer came out of the Nuremberg Trials stamped with 20 years in prison.

Then, when all others were essentially dead and gone, he came out of prison on the other side with his own explanation of his life and career during the Nazi regime with the publication of his manuscript Inside The Third Reich.

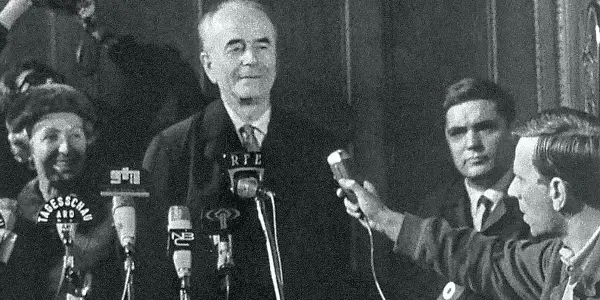

In some small way, he became a visible celebrity going on the talk show circuit and agreeing to interviews that promoted his image as an unassuming and intelligent man, who could easily switch between multiple languages depending on what circumstances required. He could hardly be considered the personification of evil, but merely a man who got caught up in one of the most infamous autocracies. He had little idea what was actually going on…

In one of his many television appearances, Speer himself says, “If one sees it from inside — when you are living inside of such a system – a fish can’t see the outside of his aquarium.” It sounds surprisingly close to the David Foster Wallace quote to Kenyon College. However, Speer uses it to dismiss his own culpability and shirk any responsibility for what the Nazis perpetrated. Whether it was individually or collectively.

The Albert Speer Biopic

Vanessa Lapa‘s new documentary Speer Goes to Hollywood attempts to grapple with his legacy in several areas. The most surprising is how Speer’s life was seriously being considered for a Hollywood adaptation. Screenwriter Andrew Birkin undertook many meetings with the architect as he tried to hammer out a script.

Although the audio recordings feel like historical reenactments, they are illuminating if only to show how serious they were about the movie they set out to make. The fact Speer is one of our primary eyewitnesses surely is suspect. Because he’s the one remaining person who can write the history for posterity in a sense.

He asks in one moment if they can make a painting out of his story – like Van Gogh would – rather than a documentary. This sounds like a ploy to blur out facts and try and smooth out some of the moral ambiguity with artistic license. Because of course this is exactly what he wants and Hollywood thrives on this kind of retelling.

Speer admits, “If the film is more and more like a drama, then I can always say, ‘No, look here. It’s a movie. It’s a film. It’s not the truth’… But if it is a documentary then it is getting difficult.”

The eminent director Carol Reed warns Birkin about portraying Speer as a dreamer thinking about all the buildings he wanted to erect. Even the phraseology of “The Thousand-Year Reich” indicates a certain vision. There’s this kind of babel-like mentality of Hitler looking to make a name for himself in the architectural landscape with the help and expertise of Speer. This is too easy of an archetype and conveniently keeps Speer out of the fray of Nazi morass.

Birkin’s mentor Stanley Kubrick supplies his own input saying he would find it very difficult to make the film if Speer’s character in the film had no idea what was going on – that is about the Final Solution – the plan to exterminate the Jewish people…

The Nuremberg Trials

If the first thread is about the movie, the second part is born out of the archival footage from the Nuremberg Trials, and this feels like a further treasure trove of historical documentation. To nick a term from Hannah Arendt, “the banality of evil” is on full display even as we must contend with Speer’s own posturings of himself as a “Good German.”

It would have been a slight tangent but a documentary focusing just on the footage of the Nuremberg trials would have been intriguing because it’s so rich with subtext. Lapa effectively contrasts the courtroom footage with images of Speer inspecting the labor plants of the Krupp company, infamous industrialists behind the Nazi war machine. But it’s not just Speer who was on trial, so there are a great many discussions that remained untapped.

For instance, when exhibits of Nazi cruelty are brought before the court, one of the defendants says all the evidence is exaggerated and a pack of lies that shouldn’t be allowed: “The German people should not be dragged through the dirt like that.” It gets to this idea of German Collective Guilt (Kollektivschuld), and whether it was fully accepted or not. How can we have Holocaust deniers if not for people rewriting history?

Conclusion: Speer Goes to Hollywood

In comparison to Hitler’s rhetoric, and based on his own conversations, Speer feels much more mundane if an altogether complicated individual. As a viewer, I felt slightly stultified. Because as much I am fascinated by the ambiguities of Speer, I hesitate to focus on him lest his own reputation overshadow all the egregious things done and enacted against those who were forced to work for him as slave labor.

His is a whitewashed telling of events from his Nazi past with only minor mention of the extermination of countless Jewish people. At most, he seems to reflect the collective philosophy of Germans after the war, using avoidant, euphemistic language like the fact concentration camps had a “bad reputation.” He doesn’t want to be implicated or fully acknowledge the atrocity. This feels only natural. He’s a human being after all. It’s also deeply insidious.

As such, I would have appreciated a hard-lining documentary devoted to the historical excavation of this man (or all these men who stood trial). On the other side of the spectrum, a narrative film that dramatized the events surrounding Speer’s later celebrity and attempts at a movie would have potentially supplied a fine character piece.

What we get feels like a mixture of both fact and dramatization, which while ceaselessly fascinating, feels slightly unsatisfying. Please don’t take this as a harsh criticism. We can still learn much with this documentary as a starting point. It just can’t be definitive.

Were you aware of Albert Speer and his historical legacy? Please let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.