NYFF 2020: SMALL AXE: Three Superb Films from Steve McQueen

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

Filmmaker Steve McQueen’s latest project, the five-part Small Axe anthology, takes its name from a West Indian proverb that says “if you are the big tree, we are the small axe.” In other words, voices that may seem small on their own can challenge more powerful ones when they are raised together. It’s hard to think of a more fitting way to describe McQueen’s saga of West Indian life in London from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s. Three of the five films in the Small Axe anthology screened as part of the Main Slate at this year’s New York Film Festival, and while they are all incredibly different pieces of art, capable of standing on their own as powerful films, together they create a vibrant tapestry of Black British life throughout the 20th century.

Mangrove

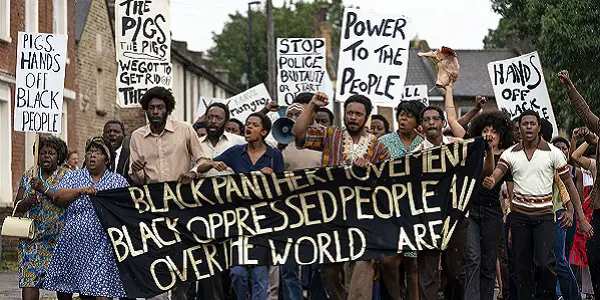

While Mangrove was not the first of the three Small Axe films to screen at the festival, it will be the first to air when the anthology rolls out over five weeks on Amazon Prime in late 2020. Based on the true story of the Mangrove Nine, it chronicles the persistent police harassment of the titular restaurant in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood. When members of the community, including the restaurant’s owner, Frank Crichlow (played by Shaun Parkes), and a leader of the British Black Panther movement, Altheia Jones-LeCointe (played by Letitia Wright), led a peaceful protest in response to these repeated raids, it devolved into violence. Later, nine of the activists were arrested and charged with incitement to riot, despite the fact that the protest only turned violent when the police showed up. The court case that followed helped shove the racist rot at the heart of the Metropolitan Police into the spotlight.

In the opening scenes of Mangrove, co-written by McQueen and Alastair Siddons, we are shown Black children playing and Black adults walking against a backdrop of a graffitied wall that includes racial slurs, highlighting the inescapable prejudice that is a part of these characters’ lives day in and day out. The importance of safe spaces is paramount when the very city you live in makes you feel unwelcome, and that’s what Crichlow’s Mangrove restaurant is supposed to be: a safe space where people can eat the spicy food of their culture and talk about the struggles of their daily lives. Crichlow is personally not interested in turning his establishment into a focal point for a movement, arguing that “it’s a restaurant, not a battleground.”

Yet Crichlow has no choice in the matter once the raids begin, with his staff and customers facing attacks with billy clubs and racist shouting on a near regular basis despite the police having no grounds for repeatedly invading the restaurant. It’s a reign of terror being carried out against the community by the very people who are supposed to protect it. Needless to say, the parallels between the historical drama of Mangrove and the police brutality that is endemic in the United States and so many other places today are impossible to ignore. There’s a reason McQueen announced that these films were dedicated to George Floyd and other Black people murdered just for being who they are; they serve as an important reminder (for those who may need one — goodness knows many do not) that these issues are not new or unique to the current leaders in charge of our countries, but part of a long, sad, enraging tradition of racist abuse from the authorities.

The entire ensemble cast of Mangrove is phenomenal, from Malachi Kirby as British Black Panther activist Darcus Howe, who boldly but unsuccessfully demanded an all-Black jury to hear their case, to Sam Spruell as Police Constable Frank Pulley, the horrifyingly racist officer who spearheaded the harassment of the Mangrove. The two standouts, though, are Parkes as reluctant revolutionary Frank Crichlow, described by another character as someone whose “blood runs purer than politics,” and Wright as Altheia Jones-LeCointe, whose defiant representation of herself throughout the trial is absolutely riveting. Wright, in particular, gives the kind of charismatic performance that should leave audience members ready to run through walls for her.

Crichlow and Jones-LeCointe have very different ways of approaching their defense, with Crichlow relying on a white lawyer and even willing at one point to take a plea deal, leading to a fiery confrontation with Jones-LeCointe and the others during the trial that I would argue is the film’s most impactful scene. The importance of unity, especially when facing a more powerful enemy, is the predominant theme of Mangrove, a film that epitomizes the unlikely strength that can be found in the small axe. It’s impossible to watch it and not be equally inspired and enraged and to feel compelled to channel that energy into some way of improving one’s community.

Lovers Rock

If Mangrove is a portrait of Black anger and resilience, Lovers Rock is one of Black joy. Co-written by McQueen and Courttia Newland, and the only one of these three films to not be based on a true story, it is an ode to the rollicking house parties that were a central part of London West Indian life when McQueen was growing up. From the thumping bass of the music to the sizzling oil of the food being cooked to the colorful fabrics swirling through the room as people dance, Lovers Rock is a film for all five senses, one that makes you feel as though you are in the room with the characters and experiencing all of their excitement and anticipation.

Similar to the Mangrove restaurant, these house parties are safe spaces for London’s West Indian community, places where they can go and dance and flirt and even fall in love without worrying about being harassed; there is even a doorman to ensure that no trouble comes through the front door. Like any party or public dance, the women start the festivities, dancing together in the center of the floor with joyous shrieks and giggles while the men lurk on the outskirts, standing against the wall with their cigarettes, contemplating which of the women they might approach later in the evening. When Kung Fu Fighting comes on, the room erupts in frenetic movement; when the music cuts out during Silly Games, the crowd raises their voices in a beautiful acapella rendition of the song, shuffling their feet and clapping their hands to the seductive rhythm. Seemingly nothing can stop them from having a good time.

A slice-of-life story that essentially brings the audience into the party and then leaves them there to enjoy themselves, Lovers Rock centers on one young couple that slowly but surely comes together over the course of the night: Martha (newcomer Amarah-Jae St. Aubyn) and Franklyn (Michael Ward). The chemistry between these two gorgeous young actors sizzles, especially when they’re dancing, feet almost rooted to the floor as their bodies move against each other. Cinematographer Shabier Kirchner, who hails from Antigua and shot the entire Small Axe series, does a magnificent job moving smoothly throughout the room and capturing all of the activity as though the roving camera is just another body on the dance floor. Kirchner’s work is a huge part of why watching Lovers Rock is such a deliciously immersive experience; the absolutely fantastic soundtrack, packed with the romantic, R&B influenced reggae music from which the film takes its title, is another. The stylishly retro ensembles sported by the partygoers courtesy of Academy Award-winning designer Jacqueline Durran also help to flesh out these characters and their time and place in a way that no amount of verbose monologuing ever could.

Throughout the party, Martha and Franklyn slowly circle each other while occasionally splitting off to deal with troublesome family members or overly aggressive men. At one point, Martha runs out of the party, but subtly menacing catcalls from white neighbors ensure that she quickly retreats into the safety of the house. This is one of only a few instances in which the racism of the outside world infects Martha and Franklyn’s beautiful night, the other being an encounter with Franklyn’s employer at a garage the next morning in which Franklyn abruptly code-switches, dropping his West Indian lilt for a deferential British tone that is all the more startling when one has been listening to him speak in his real voice throughout the rest of the film.

Yet even these moments are not enough to bring the two lovers entirely down to earth, flying as high as they are on the wave of anxious anticipation that signifies the start of something new. As Martha secretly slips back into bed in the wee hours of Sunday morning, just in time for a voice downstairs to yell that it’s time to get ready for church, her face is absolutely glowing. As the closing credits of Lovers Rock rolled, I felt that mine was too. It’s a beautiful little gem of a film, an illustration of a hyper-specific time, place, and culture that is simultaneously universal in the feelings it evokes in the viewer. That it is premiering during a global pandemic only makes one all the more nostalgic for parties like the one McQueen portrays here.

Red, White and Blue

The third installment of the Small Axe anthology to screen at the New York Film Festival is set to be the fifth and final one when it streams on Amazon Prime later this year. Co-written by McQueen and Newland, Red, White and Blue brings one back to the tensions between the Metropolitan Police and the Black community, this time from the perspective of one man who set out to mend that ruinous relationship. Whereas Mangrove showed us Black resistance against police brutality from outside the force, Red, White and Blue shows us how one man fought it from the inside, all the while dealing with the disapproval of many members of his own community, including his father, for choosing to join “the enemy.”

Portrayed by John Boyega in a career-best performance, Leroy Logan is a real-life figure who joined the Metropolitan Police in the 1980s. A research scientist who was planning on joining forensics, a friend in the force convinced him that he would make a great officer; having witnessed his own father’s assault at the hands of two white cops, Logan is motivated to change the force’s perspective of the Black community and vice versa. Yet despite acing the mental and physical examinations required to join the force, Logan immediately encounters resistance to his presence from the white officers, a resistance that quickly morphs into full-on racist abuse.

When a fellow officer scrawls a racial slur on Logan’s locker when he isn’t in the room, Logan erupts in rage, demanding that next time they at least be bold enough to insult him to his face. When Logan calls for backup and none of the white officers in the area show up, Logan confronts them at the station, not holding back any of his anger. Throughout it all, he refuses to do what both his fellow cops and his own father want most of all, which is to quit the force. He never gives up hope that his presence as an example of Black excellence can change perspectives on both sides.

Red, White and Blue has the trickiest role of these three films in the Small Axe anthology, in that it asks us to empathize with a police officer — yes, a Black police officer, but a cop nonetheless — at a time when many would rather see the force abolished altogether. Indeed, watching Logan struggle against the racism inherent in the Metropolitan Police forms a decent argument that no matter how hard you try or how good your intentions may be, you cannot reform the police. Nonetheless, it is nearly impossible to not root for Boyega in this film. His energetic presence, equal parts hopeful and angry, is just so damn likable, and his struggle to reconcile his identity as a Black Londoner with his newfound identity as a cop is rendered exactly as complicated and messy as one would imagine it to be. Without him as the film’s solid emotional center, the film would be nowhere near as good.

Red, White and Blue refuses to try and sandpaper the rough edges of these complex issues to make them more stereotypically cinematic. There is no easy solution to Logan’s problems, nor is there an easy, cut-and-dry conclusion to the film. (Spoiler alert: racism in the police force is not magically solved by the time the closing credits roll.) And while that might make it the least satisfying overall of the three films in the Small Axe anthology that I saw, it might make it the most relevant to our current moment.

Conclusion

While only three of the five segments in the Small Axe anthology screened at the New York Film Festival, the standard of quality was set so high by these films that I am now eager to see the others. The passion of McQueen and his artistic collaborators for telling these stories — stories that have too often been swept under the rug by historians and filmmakers whose perspectives are decidedly whiter — shines through in every frame.

What do you think? Which part of Small Axe sounds the most intriguing to you? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Mangrove, Lovers Rock, and Red, White and Blue all screened as part of the Main Slate at the 2020 New York Film Festival. The Small Axe anthology begins streaming on Amazon Prime starting with Mangrove on November 20, 2020. You can find additional release dates here.

Watch The Small Axe

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.