Sculptures In Time Pt. III: Tarkovsky’s SOLARIS

Stephen Borunda is an educator and filmmaker currently located in…

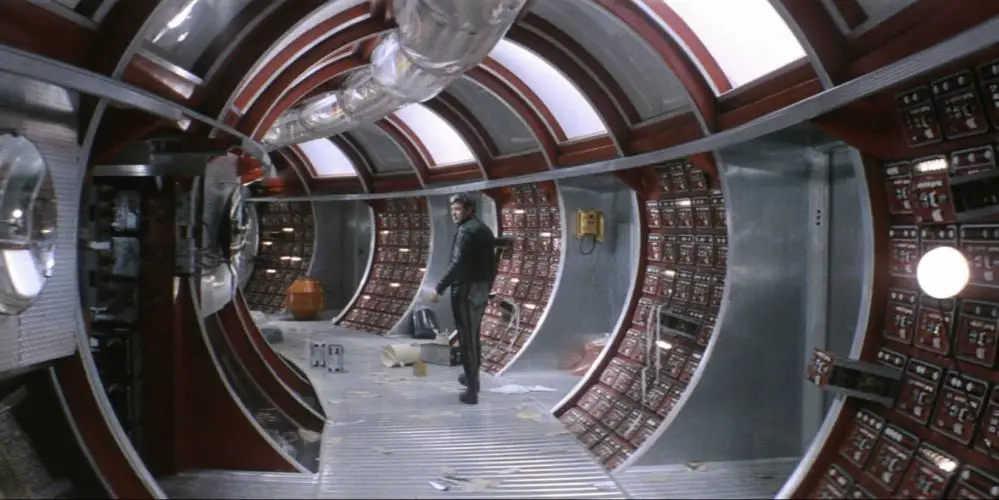

In Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris, Kris Kelvin (played by Donatas Banionis) journeys to a space station on the sentient planet Solaris in order to investigate whether the planet is still useful for scientific inquiry. Critics at the time considered Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film as the Soviet answer to Stanley Kubrick’s famed 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, the Russian auteur abhorred any comparison between his film and 2001 due to Kubrick’s willingness to deviate from the artistic truth his film held in order to appraise potential technological premonitions of the future.

According to Tarkovsky, “2001: A Space Odyssey …[was] a phony on many points even for specialists. For a true work of art, the fake must be eliminated.” For Tarkovsky, Kubrick was more interested in displaying flashy gadgets and the possible inventions of the future than asking meaningful questions about life itself.

Thus, within Solaris, we are presented with a much more restrained version of the future than most films provide us so we are not distracted from these metaphysical inquiries. For instance, during Kelvin’s interstellar space travel sequence, instead of seeing spaceships and stars, we see modern cars driving on modern highways. Tarkovsky carried his stylistic choice of simplicity throughout the film. He somehow depicts clones, a resurrection, and a living planet in such a manner that we, the audience, hardly dwell on them.

Within this visually constrained but potent film, we are told a story of the devolution and then reconstruction of a man’s morality. Interestingly enough, Tarkovsky’s ideas about the importance of visual simplicity transfer to his ideas about moral simplicity. Tarkovsky’s film suggests the power of accepting that which we do not see and cannot quantify; he begets an understanding of the indefinable value of emotions rather than statistics.

Kelvin’s Journey

In the film, mankind via Dr. Kelvin searches for some form of scientific advancement and erudite truth within the quantitative field of “Solaristics”, a scientific field based on the study of the planet Solaris. Kelvin is a physiologist (which is quite ironic since that field had been permeated by Freudian and Jungian pseudoscience). He has an estranged relationship with his parents partially due to the fact that, because of his mission, he will likely never see his father again. So, Kelvin’s final moments on earth are marred with frustration.

Kelvin claims to be capable of neutrality on the future of Solaris and Solaristics but he declares that if the scientific data warrants it, he will use radiation on the planet’s ocean. A former scientist, Henri Burton, who witnessed the powers held by the planet, attempts to plead with Kelvin about the necessity of understanding Solaris – but to no avail. Kelvin states, “I’m interested in the truth but you want to turn me into a biased supporter. I don’t have the right to make decisions based on the heart. I’m not a poet. I have a concrete goal…” Kelvin simply does not understand that emotions have already permeated his pursuit of empirical truth.

Kelvin’s sense of morality seems to be in the lineage of the utilitarian ethical system as he attempts to derive the value of actions by relying on statistical analysis. However, Kelvin is oblivious to how his emotions have managed to unconsciously work their way into these “objective” evaluations. Due to his inability to understand the emotional and spiritual basis from which man’s decisions are made, Kelvin is at first willing to make such brash declarations that falsely demonstrate man’s superiority over nature.

Once abroad the space station, Kelvin is met with hostility from the two surviving scientists, Doctor Snaut (Jüri Järvet) and Doctor Sartorius played by Anatoliy Solonitsyn (the actor who portrayed Andrei Rublev in Tarkovsky’s previous film here) because they feel that Kelvin cannot understand the complexity of life aboard the station.

However, Kelvin’s entire mission is derailed when Solaris reads his memories and spontaneously generates Kelvin’s wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk), who killed herself – as a result of Kelvin’s neglect. Kelvin’s promises of objectivity prove to be false as he immediately, out of fear, lures Hari into a ship to launch her into space. Kelvin is physically burned by his successful attempt to dispose of his wife’s clone.

Hari does not disappear for long as the planet almost immediately generates another version of her. This time, Kelvin is unable to deny both his love and grief that he feels because of Hari. She proves to be an ideal embodiment of Tarkovsky’s moral system based upon emotion. She seems to only be filled with love for others. Thus, we might critique Tarkovsky’s decision to later eliminate Hari at the film’s end as she loves Kelvin so dearly but cannot love herself. As their relationship grows tenderer, Kelvin even goes so far as too declare that this new Hari is the true Hari.

Yet, unable to bear what she and the other scientists believe to be the falsehood of her existence, Hari attempts twice to kill herself; she is finally able to commit the deed in the second attempt. Earlier in the film, Kelvin’s two colleagues transmitted an encephalogram (an X-ray of the brain) of Kelvin to the planet and after this transfer, the planet stops creating physical apparitions. Kelvin then ponders if he should return to earth or venture down to the surface of Solaris. In the final scene of the film, we witness Kelvin embracing his father who he left at the start of the film. The camera travels upwards to reveal that we are still on the planet.

Love as an Ethic

Perhaps, we might push the idea of the significance of emotions to man’s progress even further. Tarkovsky stated that within Solaris, we have the story of how “A man without love is no longer a man.” For all of the amazing scientific and technological advances that man makes, if we abandon our emotional core and our ability to love so we can satisfy data points, then we lose ourselves – and perhaps an even greater understanding of our connection to the universe. Somehow our ability to love provides us with insight into the world as a whole.

Here, I venture into my most speculative conjecture about Solaris. I propose that we can best understand Solaris by supplementing it with the arguments of Benedict de Spinoza in his philosophical treatise, Ethics. Here, Spinoza contends, “nothing can be conceived without God, but that all things are in God.” According to Spinoza, God is indistinct from his creations. We are all one and all is one. Thus, God is in the every day and his truth can be found within normalized physical and emotional spaces.

For Tarkovsky, the best way to see this nexus connected to the divine is through love. Only when Kelvin falls for Hari does his perspective shift and does he begin to have some semblance of peace about himself. How Kelvin falls to his knees to embrace his father is a moment we couldn’t have imagined from the brazen man at the impetus of the film.

At the start of the film, Kelvin lacks any sort of environmental outlook on the connections between man and nature/the divine. However, this nature found on Solaris is the being that grants Kelvin a second chance with his wife that he initially denies. Yet, this omnipotent nature may also be omnipresent, as well. For instance, the visual image of the fog is a reoccurring one and it appears during all acts of the film, suggesting that God within nature never leaves us. We might travel across the stars but we cannot depart from the greater body of God.

A possible warning that Tarkovsky issues his viewers is that if we do not realign our moral code with our emotions – that connect us to the universe at large – then we might be replaced by it. One frightening interpretation of the ending for Solaris is that the Kelvin depicted on the planet may have been a false one. Utilizing Kelvin’s encephalogram, the planet may have created a new humanity in which man can acknowledge his emotions. Only at the film’s denouement does Kelvin fall at the feet of another and confess love – an act that he struggled to do with Hari. If this ending were the true finale, as interviews with Tarkovsky suggest, then mankind should not be concerned with the ethic of love for our development – but for also our survival.

Do you see Solaris as a film about the moral progress of mankind or have I ignored its inquiries into interstellar travel? Can you present reasoning why the apparitions stopped when the planet read Kelvin’s mind? In my future articles on Tarkovsky’s remaining filmography, would you like for me to explore any other avenues that I have neglected so far?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Stephen Borunda is an educator and filmmaker currently located in Baltimore, Maryland. He completed his undergraduate and graduate education at the Johns Hopkins University. Stephen loves metaphysical films, photography, inspirational poetry, philosophy with political utility, and bashing his head in as a rugby player. Hopefully, his writing doesn't suffer too much as a result of this trauma.