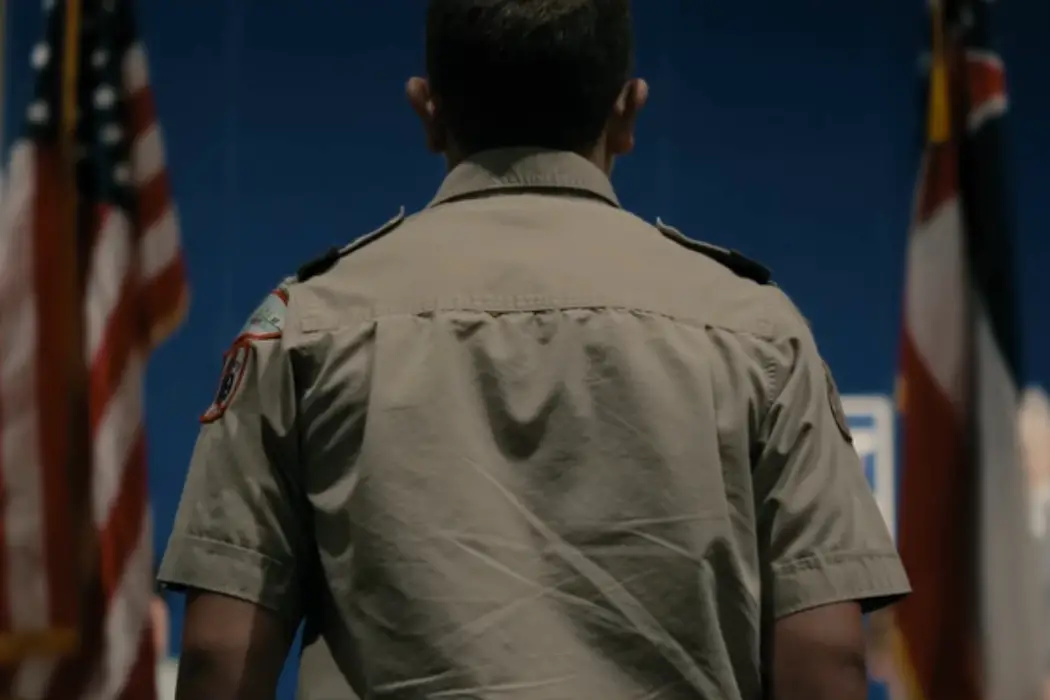

SCOUT’S HONOR: Gut-Wrenching Expose Of Sex Abuse Within Boy Scouting

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate,…

In grade school, we all knew the stories. Before I knew about the history of sex abuse within the Catholic Church, I had heard jokes about why Scoutmasters shouldn’t be left alone with Boy Scouts. The cases of actual sex abuse within the Boy Scouts of America always felt far away, like they didn’t affect us, only some other kids somewhere else. But the truth, promulgated in Netflix’s new documentary Scout’s Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America, is that “some other kids” actually means kids just like me. “Somewhere else” actually means a town that probably looks just like the small New Jersey suburb where I grew up. Five minutes into watching Scout’s Honor, I just thought I was lucky that I wasn’t sexually abused while I was a Scout, that I had an overall good experience with the program. But by the end of the film, I realized that even if I wasn’t an exception, even if the majority of kids who enter Scouting aren’t sexually abused, I have 100 percent, definitely, absolutely, without question shared a campsite, mess hall, or tent with someone who was sexually abused as a Scout.

I was in Scouting for my whole life until I became an Eagle Scout at age 16. My brothers are Eagle Scouts, too. In all our time in Scouting, there were never any scandals within our Scout troop. And the two major Boy Scout troops in town never had any adults accused of child sex abuse, but I only know that because of a searchable list of abusers online. According to that database, 107 New Jersey adults in Boy Scouts in the past few decades have been revealed to be child sex abusers. Nationwide, there are over 1,000 adult leaders who are alleged to have molested Boy Scouts.

The thesis of Scout’s Honor is that the history of the Boy Scouts is the history of sex abuse. The documentary delineates how for over a century, the organization would much rather keep its secrets buried than publicize its propensity for allowing child rapists to infiltrate its ranks.

The Crime Prevention Merit Badge

The Boy Scouts of America filed for bankruptcy in 2020. Over 92,700 former Scouts filed claims of sexual abuse against the organization. That’s just the number of people who are 1) alive today, and 2) comfortable with filing suit. How many thousands more victims have there been since the BSA was founded in 1910? How many victims took their own lives? How many don’t yet understand that what happened to them was abuse? How many feel embarrassed about speaking up? How many still feel like they can’t? Like nothing paralyzes them more than the thought of admitting what happened to them?

One cursory look at the scale of the BSA suggests that this horrific figure — over 92,700 people sexually abused as children — is only the tip of the iceberg. Over 130 million kids have passed through the Boy Scouts program in the last 110 years. Over 35 million adults have volunteered in the organization. There are hundreds of thousands of campsites in the U.S. that the BSA has access to, as well as 420 camps owned and operated exclusively by and for the organization. All of this adds up to one high-risk program that seems to be allergic to keeping children safe, one in which adults are given countless opportunities to be alone with kids.

Scout’s Honor spends much of its lean 95-minute runtime interviewing the victims. With the help of some experts, like Patrick Boyle, author of Scout’s Honor: Sexual Abuse in America’s Most Trusted Institution, the film gradually paints a mosaic of sexual trauma. Some were raped in their tents at night. Others were dropped off at hotels, where their Scoutmasters trafficked them out to other child rapists. These Scout leaders threatened the kids with violence, even murder, if they told anyone. These Scouts risked being ostracized if they spoke out. And if the Scouts were brave enough to go to Scout leadership with allegations of sexual abuse, the Scouts were often instructed to not tell their parents.

In its most shocking sequence, the documentary details a sex ring operating in Boy Scout Troop 137 in New Orleans. “They literally recruited boys into this troop, and they had sex parties at their houses,” Boyle tells us of the New Orleans troop leadership.

That was back in 1977. The New Orleans sex ring had gone on for years. The victims numbered as many as 30 boys, aged 9 to 14. And the worst part is that the Boy Scouts of America knew.

The organization kept a confidential list — the titular “secret files” of the Netflix doc — of adults accused of child sexual abuse. The list, also called a “red flag list” or the “perversion files,” specifically listed child molesters, which illustrates how rampant the problem was within Scouting. The BSA began keeping that list in the 1920s (!) with the intent of using it to render certain adults ineligible from volunteering with the organization again, and it had already removed thousands by 1935. The BSA kept the files secret solely to save face. After all, if it were public knowledge that thousands of child molesters were volunteering with the Boy Scouts of America to get access to children, my parents probably wouldn’t have signed me up for Scouting.

The secret list ensured that the BSA could remain mum about firing Scout leaders who were accused of sexual abuse. No police involvement necessary. This, as well as the organization’s reluctance to adopt any kind of ID checks, allowed some serial child rapists to simply pack up, move to another town, sometimes assume a different name, and start again.

“The Boy Scouts Did Not Abuse These Kids”

I bet you’re curious what protocols the BSA adopted to ensure that no more child molesters volunteered with the organization. Well, the Boy Scouts did… nothing. They actually would remove some members of the red flag list if someone within the BSA decided that the alleged abuser was either too old or probably dead — a decision I’m sure the many child sex abuse victims were totally cool with.

It doesn’t help matters that the Scouting leadership, as depicted in Scout’s Honor, is so dense. “The Boy Scouts of America did not abuse these kids,” says Steven McGowan, BSA general counsel from 2013 to 2022, in the documentary. “We had some bad people that got in. […] There’s no way to profile them ahead of time and to identify people ahead of time. All you can do is use a program like we do, which is to keep kids as safe as we can and to continually improve that.” Apparently, Scouting leadership is happy to treat sex abusers like forces of nature, like tornadoes or wildfires. Except real Boy Scouts know that there are ways to prevent wildfires (Fire Safety merit badge ftw) and that just because there’s a tornado coming doesn’t mean it’s going to kill you (Emergency Preparedness merit badge). Fifty percent of alleged child molesters within the Boy Scouts didn’t have kids in the program, and about half were also single. That sounds like a profile to me, if only the BSA bothered to commit the resources necessary to screen and monitor those individuals. Also, any system to screen incoming adult leaders seems to be better than the one the BSA currently employs, which is to say that I’m not really sure there is a system in place currently — rather than go through the BSA, adult volunteer applications are submitted to and processed by individual troop leaders.

Worse still, when pressed for an explanation as to what a child should do if they’re sexually assaulted in Scouting, official guidance seems to be to… tell an adult they trust. Rapists, as most of us ought to know, aren’t usually strangers — four out of five rapes are committed by someone close to the victim. Every child molester in Scouting began as an adult a child trusted. If you’re going to trust an organization like the BSA with your children — for one night a week for meetings, one weekend a month for campouts, and one week a year for summer camp — you’d hope that the people in charge can guarantee you with more than just a sweaty brow, a wavering smile, and a shrug of the shoulders that your kids are going to be safe.

Conclusion:

The biggest detractor and boon of Scout’s Honor is that it’s a Netflix documentary. Director Brian Knappenberger resists sensationalizing the subject matter the same way many Netflix docs do, but the Netflix House Style is still evident here, with an emphasis on functional documentary presentation over innovative storytelling or a director’s creative vision. The talking head segments are the worst offenders here, but serious kudos have to be awarded for the laborious chronicling I’m sure it took to assemble all the articles, news reports, and firsthand accounts to tell these victims’ stories with as much information as possible.

Knappenberger already covered the topic of sex abuse within the Boy Scouts, having directed and produced the short film Church and the Fourth Estate for The Intercept three years ago. The short film focuses mostly on Scouting’s connections to the Church of Latter-Day Saints, the church’s resistance to allegations of sexual abuse on homophobic grounds, and the story of one victim of rape. While Scout’s Honor is a better film than Church and the Fourth Estate, which is fairly unfocused, sprawling, and clearly wanting for a feature, the Netflix doc also lacks the simple radicalism of that earlier short. Church and the Fourth Estate takes an extreme, revolutionary approach to its topic and ends with one of the interview subjects directly saying that Scouting needs to end: “Can Scouting ever be made reasonably safe? My answer is, no. It can’t. So it has to go away. […] It has to be burnt to the ground. They have forfeited their moral right to this privilege that was granted by the American people.”

The short film works you to a point where that sentiment makes sense, where abolishing Boy Scouts honestly sounds like the right call. The Netflix doc, while more dogged in its respectable assemblage of the facts and its dutiful exploration of multiple cases of assault, never reaches that summit. Some people might finish Scout’s Honor and, while they might be uncomfortable sending their kid to Scouts, they might not adopt that same scorched-Earth “let’s end Boy Scouts for good” perspective.

Maybe that’s Knappenberger’s prerogative. Maybe the director wants to bring a little more nuance to this story than his earlier work had. The conclusion of Scout’s Honor has much more interest in serving the documentary’s subjects, in giving them satisfying endings to their arcs and allowing them closure for the crimes committed against them as children. It’s not really interested in addressing the doc’s arguments about Scouting as a whole.

Looking back at this review, I realize that I haven’t actually weighed in on whether or not Scout’s Honor is any good. Obviously, it’s good — any film that can trick a critic into writing for 2,000 words about its subject matter rather than its filmmaking is pretty great. As for the presentation of that material, all I can say is that I was shocked watching it. There are a few reveals that made me say, out loud, “What the f*ck?” I guess that’s the goal of a Netflix doc, but on a grander scale, Scout’s Honor is a sensitive, well-rounded attempt to bring closure to half a dozen victims of child sex abuse. At times, that more personal goal seems to eclipse the documentary’s informative objectives, but at the same time, these men’s pain and shame is the story of Scouting.

The f*cked-up thing about Scouts is that my experience of Scouting was snow-tubing and whitewater rafting. It was late-night talks with my friends in tents, chatting about movies and girls and telling jokes. It was early-morning breakfasts with my patrol while the adults banter and drink bad coffee. It was 12-day backpacking trips, hiking with burros, and listening to bearded mountain men sing decent covers of country songs around a campfire. But the men in this documentary had the worst experiences anyone could have. They had their childhoods taken from them. Their joy, their pride, their sense of self, their sense of safety. Their lives were ruined. They were abused for years, in many cases, and any attempt to get help was met with resistance from their Scout leaders and from BSA leadership.

So yeah, maybe the answer is to burn the whole f*cking thing down. Because the way it seems to me is that signing your kid up to be a Boy Scout is a roll of the dice. Maybe you have good odds of landing a troop with enthusiastic, caring adults. Maybe you have really good odds. Maybe the troops where your child’s life is going to be ruined are, like, 1 in 1,000. But do you really want to take that risk? Do you want anyone to take that risk? The Boy Scouts don’t cure malaria, after all. They go on camping trips, do some community service, teach kids to shoot rifles and use bows and arrows, and sell popcorn. Scouting is, at face value, a tool for teaching conservation and ingratiating kids to the Armed Forces (all that rifle training isn’t just for fun). The best contribution Scouting has to society is reliably pumping out a couple hundred kids a year who know how to tie a square knot. Is that worth it? Just scroll through that database of abusers, look at the map, and tell me whether you think the Boy Scouts of America as an organization deserves to exist.

Scout’s Honor is now streaming on Netflix.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate, head of the "Paddington 2" fan club.