My memory of watching Sátántangó for the first time, even though it was only a few years ago, is something akin to watching a worn-out VHS while lying at home, missing middle school because you were sick. The world it takes you into is wholly unique, and once it’s over, you feel the groggy re-emergence of the real world start to creep back in, unsure which is which.

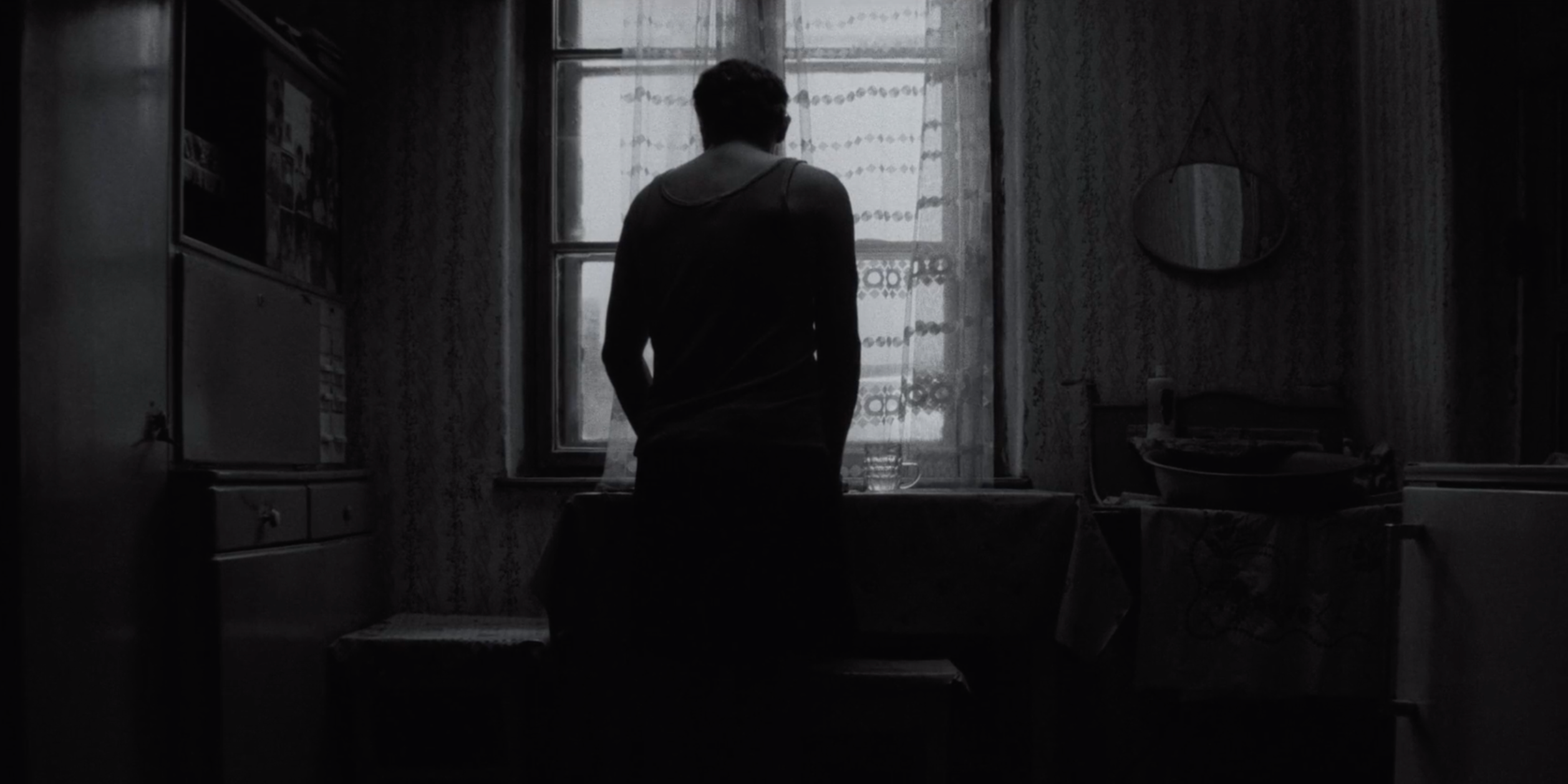

Most films can’t consume you as fully as Sátántangó; they just don’t have the time. It’s almost seven-and-a-half hour run—along with Béla Tarr‘s infamous “slowness”—is more than enough to keep away the faint-of-heart from this Hungarian master’s 1994 epic. Although every time I revisit it, I remember how engrossing and even accessible it is. Whether it is through a tired Region 2 DVD or the new 4K restoration by Arbelos, the first moments of Sátántangó always leave my jaw on the floor as I feel like I’m watching the impossible: a movie with a lived reality.

“Futaki woke to the sound of bells…”

As cows emerge from their barn, a long take slowly reveals that they are mobile, heading out across town. We track with them until they eventually disappear behind buildings. To a black screen, a narrator tells us a man is awoken by bells, even though there are none that remain standing since the war.

Light slowly fades into a kitchen, and the man peers out. We learn he’s at the house of a married woman, and learns of her husband’s plot to make off with the whole village’s yearly earnings. The two have a confrontation. A clock, real or not, ticks and the tension builds. A woman comes rushing in telling them Irimias is back, even though they all presumed him dead. How has it already been 40 minutes?

I really mean it when I say that Sátántangó is a movie that moves. It’s flowing camerawork from Gábor Medvigy, Mihály Vig’s hypnotic and carnivalesque score, Ágnes Hranitzky’s punchy if infrequent editing, all wrapped together with brilliant work from countless other collaborators (and, of course, Tarr’s direction) make for a movie that’s so easy to lose myself in.

However, those who find themselves frustrated by “slow” films will likely be frustrated here, expecting something else from movies entirely. But like Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), once you give in to the film’s unique rhythms, it offers an experience like none other. And with it’s runtime, specifically, Tarr has plenty of room to play.

Adapted from Laszlo Krazsnahorkai‘s debut novel of the same name, Sátántangó moves like it’s titular dance back and forth through its plot. Threads are introduced, scene from different angles, and oftentimes abandoned. What can start as a clear sequence gains ambiguity in its repetition. That conversation at the beginning is shown again in the final sequence before the first intermission is shown again, this time from the snooping drunken doctor’s perspective.

His notebooks on all the villagers and the ensuing hunt for more brandy opens many more questions than it answers. Once the film is past its second and last intermission, it becomes more directly linear, but at the same time, less and less is known. Irimias leads the villagers out of town in order to establish a new collective farm, his actions seem manipulative but intentions are unclear beyond potentially trying to steal their money.

It’s made even more ambiguous when we see him talking to a weapons dealer, trying to acquire bombs for unknown uses, and then giving each family of villagers new individual instructions. He’s planning for something, but we never have any idea what it is.

“The Circle Closes”

Most reviews do not get too detailed on the plot of the film, not because it’s sheer quantity is overwhelming, but likely because of the importance placed on every piece of it. Letting every sequence play out in an almost real-time, or at least, feeling as we experience time the same as the characters do, every moment gains importance, presented as cinema as opposed to the banality we might find in real life.

And it is hard to talk about only a few scenes when all of them are burned into your head trying to burst back out. Susan Sontag once exclaimed that she’d be “glad to see it every year for the rest of [her] life,” and I agree completely.

Sátántangó: A Final Thought

Perhaps the greatest testament of it is that I do not think Sátántangó is a perfect film, and I’ve spent no time arguing why that would be the case. Its precision combined with improvisation makes for many an imperfect shot or sequence, but it’s successes so far outshine them that you really have to be a disengaged viewer to even care about these perceived flaws.

It’s the kind of film that so few filmmakers have the opportunity to make, and even fewer are given the chance to have them shown and cared for so widely. I’m hopeful that its 25th anniversary can bring as much new life to the film as Arbelos’s restoration has to its images, and for many new people to get as lost as I have in its dreary Hungarian countryside.

Have you seen Sátántangó? What’s the most engrossing film you’ve ever seen? Let us know in the comments below!

The Arbelos 4K restoration of Sátántangó is playing at Film at Lincoln Center from October 18th-24th, 2019.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.