Are We Sanitizing Abuse? A Look At Age Disparity In Hollywood Casting

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film &…

In this #MeToo era, where new allegations of sexual assault or misconduct appear on our newsfeeds at a near-daily pace, many have started to question the status quo. Strides are finally being made and victims voices are being heard. However, as with any problem as complex and embedded as this, there are far more symptoms than the obvious, like sexual misconduct, that need addressing.

Hollywood has a long tradition of casting young adults in the roles of teens. This is generally considered normal and practical as employing children on sets comes with a whole host of restrictions and conditions such as tutoring, limited working hours, and requisite guardians. However, rarely do we stop to consider the results of a systematic and societal representation in film and TV of youth as adults, particularly when those roles are sexualized, as they increasingly are.

Would we, as viewers, react differently to particular circumstances in a film if the characters were played by actors of like ages, as opposed to adults several years older? The practice of casting adults has become so accepted that we hardly blink at watching a mid-20s actor play a 15-year-old on screen. Even in relatively innocent scenarios, like for example the last several films of the Harry Potter franchise, we’ve become comfortable watching children in peril.

The Science

The reasoning behind the age disparity between character and actor age, unfortunately, bears a strong resemblance to the average statutory rape defense: “He/She looks the same.” Whether or not a 16-year-old and a 24-year-old are physically comparable remains subjective and will be dissected further on, but what science tells us is that most adolescents mature physically (that is, stop going through puberty) somewhere around 15-17, though boys will often continue physical development into their early 20s. However, the social and emotional developments that occur in adolescence, defined here as 11-18, and continue through young adulthood have been objectively well documented.

It’s no secret that teenagers are essentially one giant walking emotional paradox. They seek independence but crave attention, they begin to explore their sexual identity while at the same time questioning just about everything. They may have a greater understanding of the world by late adolescence, beginning to see the nuances and grey areas, but they don’t necessarily have the experience or patience to make reasoned decisions 100% of the time. Or, to put it succinctly, “a fifteen-year-old girl may physically resemble a young adult but she may still act very much like a child since it isn’t until late adolescence that intellectual, emotional and social development begin to catch up with physical development.” (HealthChildren.org)

It’s important to note that “physical development” refers to the changes associated with puberty and not aging. Scientists aren’t alleging that all physical development reaches a peak and then halts. If that were the case, all septuagenarians would still look like teenagers. Don’t get me wrong, Helen Mirren looks amazing, but she doesn’t look 15. In reality, we never stop changing, we just stop changing so much.

When It’s Apples to Apples

Perhaps given the limited physical changes, there are cases where it’s not a big deal to cast an adult as a teen. Surely, if a PG or PG-13 film can get around child labor laws by casting adults, there can’t be wider ranging implications, right? At the very least, it certainly merits investigation and comparison to age-appropriate casting.

Yes, it was everyone’s go-to sleepover movie. The timelessly romantic story of Sandy and Danny and their friends in high school. Watching Grease and singing along as a child, they all seemed so mature, that even when I got to high school myself I still looked at them in comparison to myself and thought I could never look that grown-up. That’s because they were grown-up.

Olivia Newton-John took on the role of Sandy at the age of 28, guiding her through a journey of (yes, implied) sexual exploration that she (presumably) went through over a decade previously. Stockard Channing, playing Rizzo, was in her 30s during filming and Jeff Conaway, who played Kenicke, the father of Rizzo’s unborn child, was 28. Just a few years previously, Channing played opposite Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty (both in their late 30s at the time) in The Fortune (1975).

How would our view of this movie change if it had been cast with age-appropriate actors? It’s not that unusual to see two adults struggling with unexpected pregnancy or the early stages of a relationship (or, for that matter, for the solution to be for the woman to turn into a sexpot). Would we be as comfortable seeing a truly 16-year-old Sandy in skin-tight leather pants, leading a practically panting Danny around a carnival, but encouraging? Remember, this is the finale of the story where we are meant to be celebrating that these two “kids” made it all work out.

Watching Grease as a child (and even as an adult), there was always a sense that this group of people were all old enough to both have and deal with all the problems confronting them. The mature casting for the “teens” combined with the almost complete absence of adults in the film (at least in terms of characters), the world of Grease functions as one in which children take on major problems on their own and conquer them. It might not be the most unrealistic aspect of the film – I mean my high school certainly didn’t burst out into choreographed song and dance – but it is pretty cavalier with reality.

A decade previously, Franco Zeffirelli released his screen adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, making waves by casting two young actors in the titular roles. Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey were 17 and 16 respectively at the time of filming, and Zeffirelli was praised for his choice of casting age-appropriate actors. The film received wide-ranging critical appreciation, winning two Academy Awards, and to this day remains well rated among viewers with 74% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Audiences clearly responded to Zeffirelli’s realistic portrayal of one of literature’s great romances. Unlike in Grease, Hussey and Whiting play two young lovers not only with no clue (my favorite reading of Romeo and Juliet purports that it’s not so much a love story as a satire on the folly of young love), but who also find themselves surrounded, if not overwhelmed, by the influences of adults in their lives. It might be subtle, but by allowing the audience to truly view the youth of the leads, Zeffirelli also invites the audience to view their vulnerability and ignorance.

There are countless other examples of adults playing teens opposite other adults playing teens – Cruel Intentions, Easy A, any Harry Potter film after and including The Order of the Phoenix. And while one could certainly argue that age-appropriate casting has an effect on audience reception, perhaps making them more empathetic to the characters given increased vulnerability, there doesn’t seem to be a noticeably negative audience reception in instances of more mature casting. It certainly merits further research, which is beyond the scope of this article. We need to be asking how it affects the way society views teens’ maturity.

Situations like the above are arguably harmless. Does it really matter if there’s been a socialized representation of teens as more mature in situations that also finds them singing their sorrows to choreographed dance? Maybe, maybe not. But what about when the teen character of a film finds themselves in particularly vulnerable situations, particularly as victims of sexual abuse?

Sanitising Abuse

Audiences may not react noticeably different when teens are played by adult actors who romance other teens played by adult actors, and why should they, but what if the film alters the dynamic? Hollywood has never been exactly subtle about portraying relationships between older characters with younger counterparts, even when those pairings push the boundaries of what the law considers acceptable (or supersede the boundaries entirely). More recent examples include films like Mysterious Skin, The Only Living Boy in New York, Magic in the Moonlight and The Oranges, but there are a few films which stand out throughout cinematic history as well-received and even celebrated where an (inappropriate) age difference in a romance or relationship is the crux of the plot.

The most famous of these kinds of films remains arguably Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation of Lolita. Based on the novel of the same name by Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita serves as perhaps the single most memorable film of teen sexualization – it is, after all, a first-person account from an admitted pedophile. Ira Wells argues, in his article for The New Republic, that from her opening shot Sue Lyons’ Dolores Haze is presented to us as a “bombshell” and that Kubrick attempts to make the girl appear womanlier (and thus more acceptably enticing) than either the book or decency allows for. However, a girl may dress “provocatively” but that does not change the fact that she remains only a girl in women’s clothes.

Kubrick endeavored to cast a girl in the role of Dolores Haze AKA “Lolita” of roughly the same age as the character (12 in the book, changed to 14 for the film); Sue Lyons would’ve been about 14 during filming. Though the film makes several attempts at sexualizing her (perhaps in an effort to place the viewer in Humbert’s shoes), because of her age it never appears as anything other than a girl trying to be a woman. The film’s real failure stems from this dissonance combined with a far too likable Humbert. Not only does the novel refrain from an attempt to “mature” Dolores, Wells points out the novel is far more explicit whilst the film relies on subtext, which allows the audience to forgive Humbert as we don’t see or hear him truly violate any legal or social codes.

Indeed, the sexual nature of Humbert’s relationship with Dolores, whom he nicknames Lolita, is extremely clear in the book, as is Humbert’s view of Lolita (as a child). Meanwhile, the film, beholden to the Hays code, merely alludes to this and softens Humbert’s character to the audience. The removal from the explicit depiction of a sexual relationship allows the audience to desensitize themselves from the horror that is actually taking place, and this contributes to the film’s largest weakness – it overly sanitizes Humbert’s gross predilection. One could argue that the film forces the viewer to see Dolores/Lolita from Humbert’s (played by James Mason) perspective, but the horror of the novel results from the fact that we do see Humbert’s perspective and that even he sees her as a child.

Because of the character’s perceived “maturity” and Humbert’s relative likeability, audiences seemed to find Humbert’s attraction to the child understandable, rather than disgusting. Wells correctly points out that Kubrick transformed Lolita from the text, where she is clearly a “tomboyish, malodorous little urchin” to the cinema Lolita who has become the personification of the “precociously seductive girl.” This has leeched into film portrayals of sexualized teens extensively, in particular, the concept of “maturing” children into adults.

With the Hays Code long disbanded, filmmakers are able to be far more explicit in their work and this allows for a wider exploration of fantasy. However, over the years child labor laws, as well as social awareness, have increased, and audiences like to consider themselves “less tolerant” of things like pedophilia. But that doesn’t mean things have changed; Hollywood has just found clever ways to seduce audiences into feeling comfortable with portrayals of statutory rape – most notably by casting adults in the roles of teens.

Perhaps somewhat ironically given recent events, American Beauty stands out as a prime example of casting-character age disparity. In the film, Kevin Spacey’s character Lester Burnham develops an obsession for his 16-year-old daughter’s friend, Angela Hayes, played by Mena Suvari. This obsession culminates with the two of them very nearly having sex on the couch before Lester stops himself.

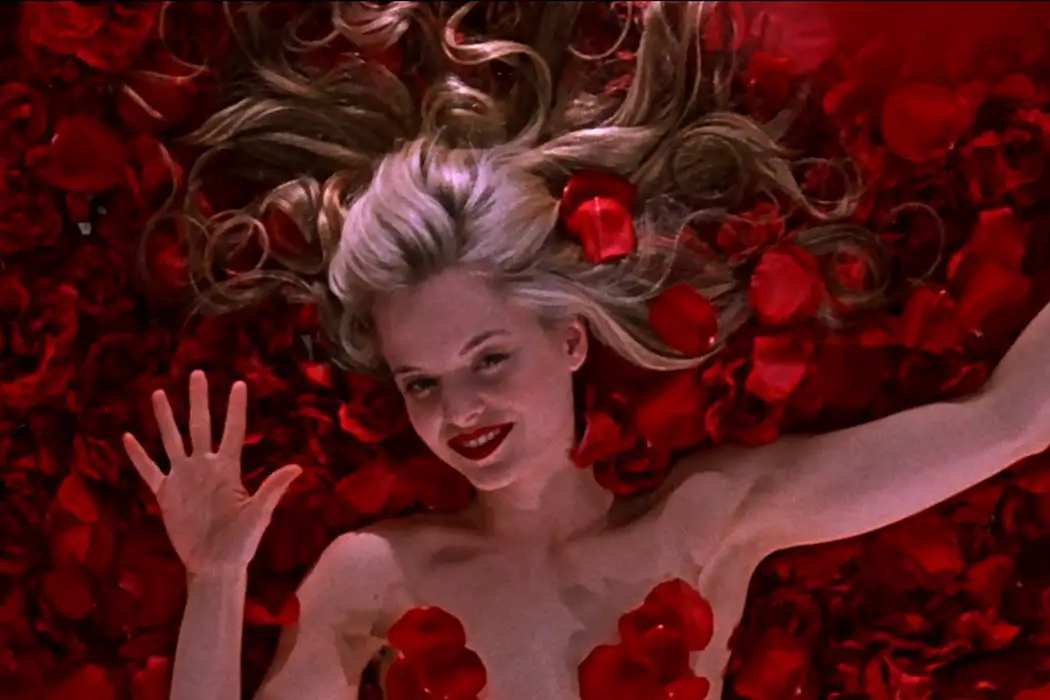

On one level, the audience knows Lester’s lust is wrong – in the original script, the two do in fact have sex and this was changed – however, despite his compulsions towards an underage girl, Lester isn’t totally savaged in the audience’s eyes. Lester spends most of the film escaping his failing marriage and boring life by vividly fantasizing about Angela. Viewers are thrust into the mind of the character (Lester) even more so than in Lolita. In this fantasy, a naked Angela seductively writes above him on the ceiling, surrounded by red rose petals. She beckons Lester to her and when she does, she is a woman fully in control of herself and in command of her sexuality and sensuality.

The Angela of reality is in far less control. Portrayed as somewhat of a vixen, Angela teases Jane Burnham (Thora Birch) that she wants to seduce her father. When she and Lester do have encounters, she comes on to him. But as the character of Ricky (Wes Bentley) points out, she’s insecure and immature and trying far too hard to seem like something she’s not. However, and this is an important difference between American Beauty and Lolita, Lester does not see Angela as a child until she says she’s a virgin.

She reveals this secret just moments before the two are about to have sex for the first time causing Lester to stop. It is supposedly this revelation that forces Lester to understand that Angela is just a girl. He has spent all previous time in the film up to this point viewing Angela as a woman to be desired. I guess to be fair, Angela looks very mature for her age…

This is perhaps because Mena Suvari was actually closer to 20 than 16 during the time of filming. Four years isn’t very long, at least, not after a person has reached sexual maturity. But, as discussed above, between 16 and 20, a person goes through countless physiological, and more importantly, psychological changes; that four-year gap is an eternity. For comparison, here’s a side-by-side of Suvari in American Beauty (right) and in her role on Boy Meets World (left) where she was actually 16.

It’s difficult to precisely pinpoint what, if indeed any, effect this might have an audience, unlike the more clear issues surrounding Lolita. However, I believe further research would show a consistently negative effect on the general perspective of sexual crimes against teens.

Casting: A Mental Re-Conditioning

It is, of course, understandable that so many films and TV shows cast actors who are over 18; they can work longer days with fewer requisite breaks and no tutoring. However, there is an imperative to understand if and how these widespread portrayals of teens as adults are sociologically affecting us as viewers, whether due to casting disparity or a “maturing” of the characters.

For many of us, particularly those of us without children, media becomes our surrogate for interacting with youth. In the same way, a meaningful representation of women, minorities, and LGBTQ communities must be considered, I believe filmmakers must also consider the way in which they are representing youth. There is a risk/reward when it comes to casting an adult, particularly if the role is sexualized in any way. On the one hand, a filmmaker may not want to expose a vulnerable young person to a particularly difficult or traumatic scene. On the other hand, removing the audience from the true nature of such events could potentially distance them to the point of ambivalence, which might even spill over into their understandings and opinions within the real world.

Should we place personal embargos on these films? Our actions have consequences, and Hollywood’s murky history of child abuse gives some pause to an argument which insists on subjecting young actors to overly sexual and difficult roles. We must find a path which simultaneously protects children and prevents audiences from desensitizing themselves to difficult subjects, and this will probably require active reconditioning on both the parts of audience members and filmmakers alike. It will be challenging and uncomfortable, but after all, part of the purpose of good art is to challenge our notions of our selves as humans.

Do you think that casting older actors as teens has an effect on audiences? Tell us in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film & tv production lecturer at the University of Bradford and is also completing a PhD about Stan Brakhage at the University of East Anglia. In the remaining "spare time", Jax organises the Drunken Film Fest, binges bad TV, and dreams of getting “Bake Off good” with their baking.