There is a delicate balance a filmmaker must strike when telling an original story, primarily because there’s a delicate balance that exists on the plane where “original” and “influenced” exist in concert. It’s an especially difficult task when an argument can be made that every original story is influenced, and thus not entirely original. What Emerald Fennell looks to suggest in her sophomore feature, Saltburn, is that the most daring films can be both. They can be unique, memorable, and fresh, all while winking toward the films of yesteryear.

So it’s a shame that Saltburn opts to kick, headbutt, and thrash — anything that will leave a mark, really — rather than wink, for if subtlety were in its vocabulary, it might make for a ride as wild as its most “shocking” moments would otherwise suggest. From its opening remarks, this is a film that doesn’t mind spelling everything out for the audience, one that prioritizes shock and awe over the basics of storytelling. Occasionally, that approach can be effective; less so if it’s the same pony pulling its lone trick twice in a matter of years.

With her Oscar-winning debut, 2020’s Promising Young Woman, Fennell showed a sort of fearlessness that was (and remains) in short supply. But the film ultimately felt empty beyond its surface-level ideas about gender roles and revenge that serves as a response to grave injustices. Similar problems plague Saltburn, a film that could serve as a clever read on outsiders whittling their way into more ideal circumstances if not for the telegraphic bombast with which it operates from top to bottom. Like Promising Young Woman, it’s a film that knows exactly what it’s about, yet has no idea how to render a fresh take on its recycled ideas. Saltburn will be divisive for many, but derivative for more.

A predictable posh romp

We begin at Oxford University, circa 2006. Oliver Quick (a devilish but predictable Barry Keoghan) is the little man on campus, one of few flies in a world full of lords. He’s yet to drop his bags in his dorm room before he notices Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi) holding court across the quad with an entourage in tow, though despite his Golden Boy status, he appears to be the least smarmy of the lot. Before long, Oliver has loaned Felix his bike as a favor, and in return — though aspects of their connection reek of pity — the seductive Felix has welcomed his new impish outsider pal into his orbit.

They take to spending the bulk of their days together, sipping pints in pubs or ogling over girls at parties, though to Oliver’s envy, Felix doesn’t have to try too hard to get them to go home with him. He’s a slim mountain of a man with a jawline sharper than most razors; notably, Felix is everything Oliver isn’t and then some. Oliver, in an incessant effort to burgeon their relationship, wears his apparent misfortune like a silk robe, flaunting tales of drug-addicted parents and a childhood marred by poverty whenever a space in conversation needs filling. When the semester ends, Oliver says he’s unsure of what he’ll do over the summer — “I don’t think I’ll ever go home again” — and Felix, albeit with some reluctance, invites Oliver to spend the summer with him at the Catton family estate which gives the film its title.

The summer that follows starts off as a montage of privilege that plays out like an MGMT-soundtracked wet dream for the guy Oliver claims to be. He’s reasonably-liked by Felix’s parents, Elsbeth (Rosamund Pike) and Sir James (Richard E. Grant), and Felix’s “sexually incontinent” younger sister, Venetia (Alison Oliver, given more to do here than she was as the lead in 2022’s BBC adaptation of Sally Rooney’s “Conversations With Friends”), though they all treat him as an object of fascination more than a house guest. Only Felix’s cousin, Farleigh (Archie Madekwe) and the chilling family butler (Paul Rhys) find his sudden prominence in Felix’s life a touch peculiar, an instinct Oliver rewards with his behavior, even if unseen by the cautious duo.

Does Oliver see in Felix an object of fascination, or an easy target? That’s the most obvious question a viewer may have, one that doubles as the question Saltburn seems most interested in, even if it doesn’t quite know how to answer it. The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle, but how it gets to said truth is even messier than what the characters at the center of the question endure along the way. It’s also convenient, over-explained, and dramatized within an inch of its life. In short, you don’t need to be an ace detective to deduce this film’s roadmap from the jump; you just need to be familiar with The Talented Mr. Ripley and Brideshead Revisited.

Something is amiss

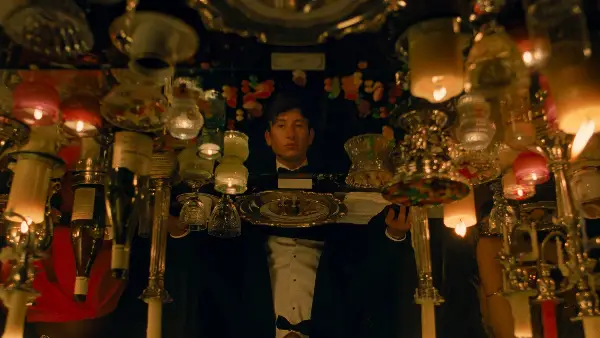

To Saltburn’s credit, much of its non-predictable output is humorous, even enriching, each individual character study proving more beguiling, at the least, than the last. Yet of course, what awaits around the corner of many of the film’s most alluring moments are terribly telegraphed reminders of the careless imitation with which this film operates. It has hardly anything particularly new to offer beyond the images cinematographer Linus Sandgren creates. His 1.33 aspect ratio reels of preening setpieces draped in garish colors feel more like distractions amidst a film that operates with no intent beyond being a provocation.

Therein lies the fear I have for Emerald Fennell as a filmmaker. I’m fairly certain that she’ll remain successful given how passionately her most ardent fans will go to bat for her style, but I feel that she, just two divisive films in, is quickly carving out a niche for herself that no great storyteller should strive for: being a provocateur without a shred of substance to go with it. Fennell has a knack for making beautiful, empty disasters that are impossible to take your eyes off of, for better and for worse at the same time.

A great many sequences in Saltburn will go down as the most shocking of the year, but to what end? The majority of them — none of which I would dream of spoiling, as I’ve been baffled to see multiple critics do already — are sure to elicit queasy murmurs from the audience, but that’s where the stakes stop. They offer nothing to the characters involved beyond shock and awe, reasserting truths we already knew based on the increasingly evident abhorrent nature these characters have been fostering since the film’s onset like bacteria in a lab.

Many would be apt to argue that we need more divisive films these days, fresh escapes from the uncomplicated fare we’re often subjected to at the multiplex. But there’s divisive and there’s derivative. There is also panache and there is pastiche. Fennell manages, almost impressively, to paint her films with all of these elements at the same time, but one overarching problem remains: She’s too keen to watch your jaw drop to the floor than to get you invested in her stories in the first place. If you’re making something from scratch, you have to have a detailed, intricate plan to get you from point A to point B. I’m not convinced Fennell knows how to do that yet. She’s more interested in blowing things up than she is building them.

Saltburn was released in theaters on November 17th.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.