Seeking Our Story: Leni Riefenstahl & The Responsibility Of Storytellers

All articles contributed by people outside of our team are…

Renowned German dancer and film actress Helene Bertha Amalie “Leni” Riefenstahl directed her first feature, The Blue Light in 1932 at age 30. Soon after, perhaps through her rumored relationship with führer Adolph Hitler, Riefenstahl received a commission from the Nazi Party for The Victory of Faith (1933) followed by Triumph of the Will in 1935, and Day of Freedom: Our Armed Forces, also in 1935, which depicted a mock battle scene staged at the seventh Nazi Party rally.

Filmmaking Prowess

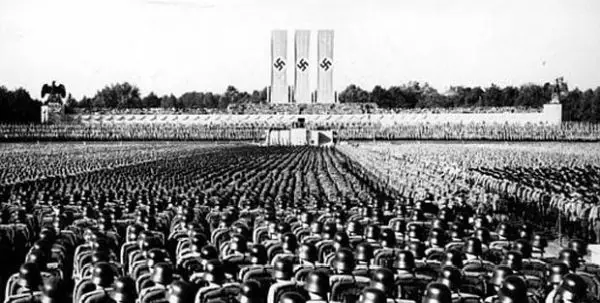

Riefenstahl’s portrayal of the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, Triumph of the Will exemplifies propaganda filmmaking. Riefenstahl commented that Hitler, “wanted a film which would move, appeal to, impress an audience which was not necessarily interested in politics.” Through visual repetition and an appeal to emotion over reason, Riefenstahl created a masterwork that announced Germany’s rise from political instability to world superpower.

Though claimed as cinema vérité, Riefenstahl carefully choreographed over one-hundred and seventy technicians throughout the city of Nuremberg for Triumph of the Will, and rehearsed sequences as many as fifty times before the anticipated rally, which was staged largely for her cameras.

Two of Riefenstahl’s most significant films Olympia Part 1: Festival of the Nations and Olympia Part 2: Festival of Beauty, both documented the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Through extremely strategic directing choices, she pioneered techniques that are reflected still today in sports photography.

Before being taken prisoner by the Allies at the close of World War II, Riefenstahl completed her last narrative feature, an adaptation of Tiefland, also known as Lowlands. After her release, Riefenstahl spent the 1950s and 1960s photographing the Nuba peoples of Sudan and began filming “Die Schwarze Fracht”, or “The Black Cargo”, an uncompleted movie on modern slavery.

Riefenstahl also continued to work as a photographer, even documenting the 1972 and 1976 Olympics. After photographing the coral reefs for years, Riefenstahl released a compilation of her diving videos titled Impressionen unter Wasser, or“Impressions of the Deep” in 2002. Riefenstahl died in 2003, shortly after her 101st birthday.

Seeking Our Story: Screening of Triumph of the Will

This week the Seeking Our Story and the University of Southern California School of Cinema Arts Department presented Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will as a cautionary tale on the power of art in politics. This screening opened with an academic panel featuring Wolf Gruner (Founding Director of the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research), Michael Renov (Vice Dean of the USC School of Cinematic Arts) and Steven Ross (Director of the Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life). These gentlemen prefaced the film with a historical and aesthetic understanding of Riefenstahl’s place in the rise of German fascism.

Though the entire experience both chilled and boiled my blood, one image stirred me to gasp in alarm. After hours of repetitive, mind-numbing Nazi iconography this one shot burned into my memory:

- Soldiers march through the central plaza of Nuremburg.

- Hitler hails the army, his army.

- Newly minted flags dance before The Frauenkirche (“Church of Our Lady”).

- Suddenly the camera looks down upon the rail lined bricks of the street as an army of shadows in salute march across the screen followed by rows and rows of German men in uniform.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2VpNqqBdGg&feature=youtu.be&t=7m42s

Jarring in both its inventiveness and visual abstractness, this shot alone shocked me into understanding what Dr. Renov meant in quoting author Susan Sontag on the aesthetics of fascism, “a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behavior, and extravagant effort; they exalt two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude.”

I have to hand it to Riefenstahl as a cinematic artist. Her eye for movement – vaulting cameras, dancing flags, interwoven arms in Nazi salute – built a poetic lyricism that must be acknowledged. The rhythms of drums and military marches, both in the sound design and visual cutting of each sequence, carried me through this horrific display of military power as if I floated above in a plastic bubble of false security. Riefenstahl’s films must be seen consciously both for their artistry as well as for the lessons they carry in the potency of film linguistics. I encourage you to view her work. To see it for what it is. To see it for what she has accomplished. To recognize how she shaped the storytelling of heroism, wherever camouflaged in our culture today.

Ruth Starkman wrote that Riefenstahl, “presides as the ‘mother’ of modern media” and The Economist claimed upon Riefenstahl’s death that Triumph of the Will, “sealed her reputation as the greatest female film-maker of the 20th century.” Yet, as Irene Runge of Berlin’s Jewish cultural center told The Guardian upon Riefenstahl’s death, “You have to take responsibility for your past. She didn’t. That is what people will remember about her.”

During the post-war trials, Riefenstahl distanced herself from her Nazi affiliates, claiming that she was coerced into working for the Party and that she was unaware of the genocide that occurred throughout Germany during Hitler’s reign. In reviewing a 1994 documentary on Riefenstahl’s life, critic Roger Ebert noted that, “she has rehearsed over the years an elaborate explanation and justification for her behavior” and “her unconvincing, elusive self-defense that continues to damn her.”

Can Riefenstahl’s artistic contribution stand separate from the political environment during her early career? Does art exist outside of the cultural influences which shape the artist?

Take these questions to heart, especially now as we must remain present and mindful, aware of our own power to influence the minds and hearts of our audience.

About Samantha Shada

Samantha Shada is a Los Angeles-based director. She programs Seeking Our Story, screening influential films directed by women.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

All articles contributed by people outside of our team are published through our editorial staff account.