“When It’s Not Your Turn” – Revisiting THE WIRE: Socioeconomics & Sanctioned Institutional Gangs

Digital Media Program Coordinator and Professor at Southern Utah University…

For nearly 20 years, HBO’s The Wire has stood as the single greatest achievement in narrative television. It stands at the pinnacle as the perfect example of depth, power, and impact in storytelling. The series’ depictions of socioeconomic disparity and the very legitimate reasons behind the actions of those trapped within that disparity are palpable, while the stinging rebukes on display within the show’s societal mirror are among the most compelling in film history.

The series was co-created by former police reporter David Simon, who spent much of his career as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, and former police officer and teacher Ed Burns. It uses mostly fictional characters to depict a very real situation: an inner-city gang war between the police culture and the drug culture, set in Baltimore, Maryland.

The term “gang war” is distincly relevant: despite increased general awareness of police brutality, many Americans remain content to assume that officers live by some moral or professional code guiding and preventing them from doing anything remotely shady, let alone criminal. One of the first and most important lessons a viewer will learn from watching The Wire is that this assumption is woefully incorrect. As Simon himself notes in the commentary on the first season’s DVD set:

[The Wire is] really about the American city, and about how we live together. It’s about how institutions have an effect on individuals, and how, regardless of what you are committed to, whether you’re a cop, a longshoremen, a drug dealer, a politician, a judge, a lawyer, you are ultimately compromised and must contend with whatever institution you’ve committed to.

“Come at the king, you best not miss” – Omar

A storyteller’s greatest responsibility is societal critique, and The Wire is a prime example of how to fulfill that role. In the first episode of season four, we’re introduced to a remarkably simple storytelling device that perfectly represents the show’s overall message.

Marlo Stanfield has taken over as kingpin and principle antagonist for the police force, having conquered the corners Avon Barksdale left behind. When Avon (played by Wood Harris) had been running the trade, the body count was predictably high. Suddenly, with Marlo (Jamie Hector) in charge, Baltimore’s officers are confused by what seems to be a low body count for a successful drug empire.

From the first episode of Marlo’s reign, the viewer is clued in to his secret. Chris and Snoop (Gbenga Akinnagbe and Felicia “Snoop” Pearson), Marlo’s main muscle, have been hiding the bodies in boarded up abandoned apartment buildings, covering them with quicklime, and wrapping them in plastic material, such as a shower curtain. Finally, they restore the boards to the doors and windows, and no one is the wiser.

For any gang wanting to hold on to power, murder is the most effective iron fist. However, it creates an inconvenient and incriminating problem if left out where everyone can see. Marlo has figured out an effective way to do what is necessary in order to maintain power, while keeping the incriminating evidence in the periphery, just out of sight.

In this and subsequent similar scenes, the viewer is introduced to a metaphor for the socioeconomic inequality The Wire strongly criticizes. As the show depicts, in order to maintain power and position, sanctioned institutions quietly go about business that is shady at best, criminal at worst, and continually find ways to “board up” anything incriminating.

The difference between metaphor and reality, however, is only more damning. While the officers chasing Marlo and his crew are constantly looking for something to incriminate him, socially-sanctioned institutional misconduct is intentionally overlooked by the comfortable who directly or indirectly profit. Worse, this self-imposed ignorance ultimately leads to perpetual prejudicial legislation, such as: Citizen’s United, handouts and protections exclusively for the wealthy, and the constant disproportionate influence of the affluent in American politics, just to name a few.

In Marlo’s strategy is a clear parallel to America discarding the “inconvenient” parts of society (the collateral damage of ensuring socioeconomic inequality and continued wealth among the elite, often with bodies just as real as those tied to gang warfare) and pretending they don’t exist; in short: boarding the doors and windows, and placing the evidence in the periphery, just out of sight. Author Stanley Corkin summarizes:

[The Wire] opens a discussion substantially focused on how urban despair is created and enabled by the institutional structures that articulate the terms and limits of ghetto life. Drugs are not so much the catalyst for misery as a symptom of the extremes of inequality and social isolation. And in developing a systemic view of drug use and its connection with race and class, Simon develops a place-specific narrative that delves into the social effects of isolation… The Wire focuses on the economic impact of the decline of the public sector, the effects of the globalization of finance, the far-flung production of all commodities, and the massive social inequality resulting from these policies and practices. (pp.7-8)

“Deserve got nuthin’ to do with it” – Snoop

Another common and simply incorrect view held by many upper and middle-class Americans is that these inner-cities are places of desperation, filled with people who are unable and unwilling to “work their way out” or take advantage of the numerous opportunities presented to them (Chaddha & Wilson, 2011, p. 165). In reality, people are incredibly resilient, and will find ways to make the best of any situation, often creating for themselves what they weren’t born into: including but not limited to an income, a purpose, and a few simple comforts.

As the series depicts, many of these inner-city “lower-class” citizens are brilliant individuals who have created a purpose for themselves using one of the few options available to them. There always exists at least one driving force that keeps a person going. That purpose is as varied as humanity, and the old adage to “bloom where you’re planted” applies to many different types of terrain. If someone is “planted” in an environment hostile to “blooming,” they’ll still do everything they can in order to grow.

“I got the shotgun, you got the briefcase” – Omar

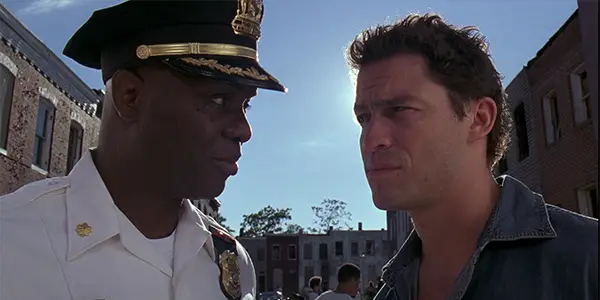

A character of note and fan favorite is Omar (Michael Kenneth Williams), a homosexual African-American man who has found a way to take advantage of the drug war to meet his own needs. Omar’s ideology is fittingly simple: personal preservation above all. Early in the series, Omar is interrogated by officers McNulty (Dominic West), Freamon (Clarke Peters), and Greggs (Sonja Sohn). In no simple terms, he explains that he has no problem at all helping the police.

Such a statement may come as a shock to some viewers, as it is commonly assumed that “snitching” to officers is always a capital offence among these groups. However, such viewers misunderstand Omar’s purpose: to preserve and protect himself and anyone under his care. Sometimes, this means playing both sides for his own benefit.

The caveat, however, is that his willingness to help stops short of any obstruction to his personal goals. Omar is king of the hill primarily because he clearly understands that in order to thrive, an individual must make the right choices for self-preservation, even if it puts others in harm’s way. This is especially so if the system to which the individual is beholden offers very little choice.

With no allies and no options, that individual will do what it takes to rise above the competition. In the end, it’s about survival. As Omar says during this exchange: “The game is out there. And it’s either play or get played.”

It shouldn’t be assumed, however, that the very real people represented by characters like Omar are incapable of morality. There’s a very simple rule to remember regarding socioeconomic status and the resulting cultural paths people usually follow: morality is fluid. In The Wire’s opening scene, the subtle differences between Detective McNulty’s moral code and the moral code of the citizen he’s questioning (Kamal Bostic-Smith), is perfectly depicted in just a few minutes.

In one of the most clear, concise and perfect opening scenes in television history, both characters are somehow moral, decent, and even laudable, despite seemingly dichotomous goals and ideals. The differences lie not in their general sense of morality, but in their individual culture: cultures born of distinct socioeconomic backgrounds.

Brilliantly, the morality of Detective McNulty is never actually articulated in this opening scene. Instead, his morality is assumed by the viewer, based simply on the understanding that he is an officer of the law. This assumption, not forced or suggested in any way by the scene itself, is a perfect foundation upon which is built the ultimate critique of convention conveyed both by the scene, and ultimately, by the series as a whole.

The scene closes with the sudden “twist” of the interrogated citizen’s strong moral code being fully on display. McNulty askes the citizen, who was a friend to the murdered “Snot Boogie,” a question (one that to the ignorant viewer, may seem perfectly reasonable): why he and the rest of his friends allowed Snot continued participation in a weekly game, wherein he would try to steal the winnings each and every week. The citizen almost scoffs at the underlying assumption of the question: that preventing Snot from participating was ever an option. His response: “Got to. This America, man.”

Not only did they never prevent Snot’s participation in the game despite knowing he would invariably try to steal the winning pot, they had never, nor would ever, even consider such a course of action. Simply put: Snot’s freedom to participate and be involved was more important than the frustrations brought about by his attempted thievery. McNulty’s assumed morality is questioned, while the so-called criminal’s powerful moral code is irrefutably proven. The viewer is left with a completely altered perspective after only three minutes of starting The Wire, the first of many challenges to convention throughout the series.

“This game is rigged, man” -Bodie

Consider an uncomfortable but obvious reason behind socioeconomic disparity: the apathy of those who are comfortable. It seems understandable; if you’re born into comfort, you’re likely to do everything possible to retain that comfort. The need for happiness and security is a universal human need, and those of low socioeconomic status are just as human as those of higher status.

This universal desire, combined with the vastly disproportionate power of the higher classes constantly being used to retain their position, creates one of many reasons those of lower classes often turn to the drug trade. Simply put, it’s the most beneficial option available when the affluent have already taken everything else.

This situation is what creates and perpetuates the inner-city drug trade culture. Indeed, societal “punishment” usually meted out in unfair bias against African American and Latino men, is viewed among its participants as simply part of the drug trade “game,” an occupational hazard. Few statistics more patently implicate America as a racist country as that of having the highest prison population in the world, with blacks being incarcerated at five times the rate of whites. Sociologist Anmol Chaddha and Harvard University Professor William Julius Wilson suggest that the racial divide in incarceration rates comes in part through intense police focus on inner-city culture, where they spend their days looking for reasons to make arrests:

A fundamental feature of the era of mass imprisonment is that incarceration has effectively been decoupled from crime… [T]he incarceration rate has grown consistently since 1970, while official measures of crime increased in the 1970s and declined in 1990s…

Faced with the expectation of producing numbers, police departments are encouraged to focus on poor, inner-city neighborhoods to provide a greater number of arrests, especially by targeting the open-air drug trade. Much police activity in The Wire is intended to “juke the stats,” as the officers describe it. With media attention on crime and the pursuit of measurable results, greater public pressure makes more intense policing a political necessity. Since imprisonment directly constrains the economic opportunities of ex-offenders and has deleterious consequences for their families, the social conditions of inner-city communities deteriorate even further. In cities across the country, mass incarceration has an enduring effect on the concentration of disadvantage. (pp. 169-170)

“The bigger the lie, the more they believe” -Bunk

Throughout each season, The Wire takes an American institution and, using a brutally realistic approach, exposes its flaws; flaws that are usually set up by the aspirations of affluent individuals at the expense of the whole. The subject of season one is the police force itself; for season two, financial and economic systems; season three, political disruption inside the the criminal justice system and more specifically, the drug war; and for season four, the education system. Season five is somewhat unique: in a stroke of masterful brilliance, Simon and Burns turn the show on its head, speaking to the very fact that The Wire is so effective as a societal mirror. In this final season, the institution of television and media, indeed, the series itself, becomes the target, and presents to the viewer the show’s “internal compromises and failures” just as it did with other institutions throughout the first four seasons.

As the viewer creates within themselves a perfunctory “rage of justice” from their comfortable couch, they are the object of a scathing rebuke. Throughout all five seasons and their individual targets, however, there is clear aim at the larger, overarching target of socioeconomic inequality, a problem exacerbated by each of the highlighted institutions. Watching (or re-watching) the series with an eye focused on The Wire‘s overall critique of societal convention, one begins to discern the illusion of luxury for the “deserving” being propagated by the modern elite and their institutions of perpetual wealth, all of which David Simon refers to as “the indifferent gods” of our time, a direct parallel to the gods of Greek tragedy.

The characters in this very real tragedy are often victims of the convention laid out by “gods” who spend their time perpetuating the institutionalization of selective advantage. The impossibility of their circumstance often requires individuals of lower socioeconomic class to reconcile within themselves the pointlessness of their efforts. This feeling of futility is consistently reinforced by the very institutions (gods) that stand to profit from retaining the status quo, and keeping the lower classes (mere mortals) “in their place.” The entire point is that there is no point, or, as David Simon defines the theme, an “irrevocability of fate.”

Throughout The Wire, these American institutions, and the middle and upper-class apathy toward the obvious deficiencies thereof, is strongly critiqued. One of the most powerful examples of that critique comes in the third season, wherein one of the few characters actually endeavoring to create positive change decides to use his position to try an experiment. Baltimore PD Major Bunny Colvin (Robert Wisdom) understands more than most that in the drug war, both sides experience frustration and very often, pain; or, as former officer Roland Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost) cynically but accurately puts it: “No one wins. One side just loses more slowly.”

Understandably, Colvin is not satisfied with the status quo. The system is having little to no positive effect, despite constant pressure from all sides. Finally, he comes up with an idea: a paper bag for drugs. Drawing on the simple solution to public drinking that was the brown paper bag, Colvin suggests that a single, mostly uninhabited block in downtown Baltimore can be used as a “paper bag” for drugs: if dealers agree to move their business to that area, police will turn a blind eye to the distribution.

In the end, Colvin unfortunately loses his career over that city block, which comes to be known as “Hamsterdam.” His superiors and Baltimore politicians shut the project down despite the fact that it worked: violent crime dropped, and the citizens under Colvin’s jurisdiction finally felt safe. Simon‘s critical message here is clear: the upper echelons of the police force and their managing politicians care little for real results and real change, and instead want to maintain their own comfort and position, making sure middle and upper-class taxpayers continue to do their part in keeping the money flowing.

The solution, so obvious and, thanks to Colvin, proven to be effective, is disregarded in favor of continued gross inequality and perpetual loss of life resulting from a pointless drug war. The almighty dollar, wielded exclusively by the powerful, wins again, and the true morality of the elite is shown to be less than that of the drug dealer.

To the comfortable middle and upper-class citizen, The Wire‘s message is resolute: “This is just as much your fault as anyone else’s.” There’s a feeling of animosity, to say the least, between the wealthier middle and upper classes, who often view drug dealers as the dregs of society, and inner-city gangs, who view the wealthier classes as oppressors. In reality, both sides are right to a certain extent; however, as is usually the case, history will side with the oppressed over the oppressor.

“The king stay the king” -D

Like characters in a Greek tragedy, the system’s victims are forced to create meaning for themselves in the face of an existence stripped of meaning by the rest of society. In The Wire, Simon and his team created a show rife with staunch Lukacsian realism, or the idea that “art [is] the objectification of the sociohistorical development of humankind.” (Levine, p. 3) This approach, defined by the team’s dedication to realism, created a world so well-established and accurate that the show has often been referred to as a visual novel; having such intricate detail and a seemingly effortless sense of time and place, as though it were previously established in some written backstory the viewer subconsciously assumes they must have read at some point.

This is most thought-provoking when the more mindful viewer realizes that the Lukacsianism present in The Wire’s signature realist style “perpetuates the classical humanist ideal that humankind is an end in itself.” (p. 48). This stands in stark contrast to Simon‘s “irrevocability of fate,” and yet, perhaps, our shared human ability to relate to this seemingly dichotomous theme of false hope in the face of futility is exactly why the show, as a whole, works so well.

Citizens living in inner-city cultures do not lack wisdom, although oblivious upper classes often assume as much. In order to fulfill the universal desire for comfort, inner-city citizens are forced to do whatever is necessary to survive, and ultimately thrive. They understand the desire for comfort, as much as, if not more so, than the affluent, who often inherit their status. These inner-city citizens also understand very well how the upper-classes think, as shown beautifully in the character of D’Angelo Barksdale (Lawrence Gilliard Jr.), simply referred to as “D.”

D is the nephew of kingpin Avon Barksdale, the principal antagonist throughout the first three seasons of The Wire. It’s clear from very early in the show that D, and metaphorically, the wider participants in the drug trade, have a clear understanding of how privilege works. While speaking to his distributors as they enjoy some chicken nuggets, D scolds them for assuming that whoever invented the chicken nugget is now rich and living like a king. He explains his (likely correct) assumption that whoever invented them is still “down at the basement” in order to “make some money for the real players.”

As he later explains while teaching his two young frontmen the rules of chess, “the king stay the king” without exception. The wisdom of these inner-city characters is depicted clearly throughout The Wire, and by contrast, the show is not shy about depicting some institutionally-sanctioned officers as plainly idiotic. A clear challenge to convention is manifest in the viewer’s coming to realize that the police force is just as much a “mixed bag” of the wise and foolish as the inner-city gangs.

D’s theory regarding the futility inherent in any pursuit of self-actualization within such a prejudiced system is validated, as all three of the characters involved in that chess conversation, D himself, Wallace (Michael B. Jordan), and Bodie (J. D. Williams), are killed by the end of the show, not by the enemy, as the rules of chess would imply, but each by other participants in the drug trade, as they cooperate, or are assumed to have cooperated, with the police. D is murdered while in prison, where he voluntarily went rather than provide the police with substantive information on Avon’s operation. While there, he is murdered in retaliation for what little information he did provide. Wallace is also murdered in retaliation for snitching, ironically by Bodie. Finally, Bodie is murdered after he is seen conversing with Officer McNulty, despite having not revealed anything.

Poignantly, Bodie had initially shrugged off the allegorical intent of D’s chess lesson, saying in no simple terms that while he may be a pawn, he’s a “smart-ass pawn.” At the end of season four, his hopes deflated, he refers to himself merely as one of the “little bitches on a chessboard.” This observation turns out to be his last. As put by University of Michigan Professor Paul Allen Anderson:

If the chessboard flickers with the radiant ideal of upward mobility for a “smart-ass pawn,” the thoughtful pawns of The Wire find all paths to that ideal blocked. Chess’s crystalline allegory of work and institutional life stands in stark contrast to the less rule-abiding dynamism of “untethered capitalism run amok” in the game and elsewhere.

“They’re not learning for our world; they’re learning for theirs” -Bunny

The Wire’s most important message may be found in season 4, a solemn depiction of socioeconomic inequality’s heartbreaking effects on the education of America’s children. Status, including individual advantage and disadvantage, is indoctrinated into the minds of society’s citizens from birth. It’s more than infuriating to be a victim of a previously established, destructive but completely legal, lethal and yet almost universally sanctioned institutionalized discrimination.

Still, citizens of lower socioeconomic status are forced to reconcile within themselves that their birth (race, gender, and status), something completely beyond their control, is, in the eyes of the rest of society, the only real measure by which their place on the socioeconomic ladder is determined. If people placed in such extreme circumstances are ignored and just told to “bloom where you’re planted,” they will find a way to do exactly that, even if it involves drugs, and in extreme cases, murder. As the affluent have rarely had to contend with such obstacles to success, they are the least qualified to make real, lasting change, and yet have rigged the system in such a way as to give themselves exclusive rights to political leadership.

In season four, Bunny Colvin, having lost his policing job due to the failure (see: success) of Hamsterdam, struggles against that very problem when he decides to try and make a difference in the city’s schools. As part of an experiment meant to help improve the education of middle school kids, Colvin ends up working with a group of deeply troubled students. The show makes it clear very quickly that the culture in these inner-city schools is a radical departure compared to the experience of middle and upper-class citizens.

The kids understand the way things work on a far deeper level than many of their more affluent peers. They know their position in society, their role as “corner boys,” and they’re prepared to embrace it, especially considering they’ve been offered little choice in the matter. These kids understand that their lives will very likely be cut short, and yet, they’re fully prepared to accept that possibility. The situation created by the system has children embracing an early death in the name of that vindictive and egotistical phrase: “bloom where you’re planted.” As The Wire shows over, and over, and over again, we are clearly doing something wrong.

Some history here will provide context that may further enhance a viewing of season four. Fifty years ago, sociologist James Coleman was commissioned by the U.S. government to conduct a research study. He was asked to determine the best course of action regarding the desegregation of the American school system, as the government needed some kind of scientific endorsement to help sell the new normal resulting from the then recent (and now famous) Brown v. Board of Education.

Coleman compared what he called “social capital” across student groups, focusing specifically on the conditions eventually defined as “socioeconomic status,” and concluded that this previously unconsidered factor was critical in determining the likelihood of a student’s success in school. Officially titled the 1966 Equality of Educational Opportunity Study, The Coleman Report demonstrated in no uncertain terms that social inequality perpetuates educational inequality, and is the direct result of a slow but systemic sabotage of any progress made toward the antithetical ideal.

Educational authors Gollnick and Chinn write: “Families usually do everything possible to protect their wealth to guarantee that their children will maintain the family’s economic status. The barriers that exist in society often lead to the perpetuation of inequalities from one generation to the next.” (p. 76) As Pryzbylewski makes the transition from police officer to middle school teacher in season four, he discovers just how difficult it can be for teachers to help disadvantaged students succeed, especially in a social context such as the one found in Baltimore or other inner cities. Gollnick and Chinn continue:

Wealth and affluence can create an uneven playing field for many students as parents with larger incomes use their power to ensure that their children have access to the best teachers, advanced placement courses, gifted and talented student programs, and private schools. Parents are able to financially contribute to the hiring of teachers for programs such as music and art, which many school districts can no longer afford. They will not tolerate the hiring of unqualified or poor teachers. On the other end of the income spectrum are families with little input into decisions concerning the education of their children and who cannot afford to contribute the resources to maintain a full and desirable curriculum. (p. 84)

Tragically, educational convention insists that there are many complicated factors necessary in order to be considered “disadvantaged,” most of them societally imposed, and many of them revealed to be painfully arbitrary under even the slightest scrutiny. Studies have shown that students from poor or otherwise disadvantaged homes often arrive at school, on their very first day as Kindergarteners, less cognitively prepared than their peers, another tragic consequence of equality’s systematic sabotage at the hands of the affluent. These students are disproportionately racial minorities.

It’s very clear that unbalanced advantage perpetuates an unjust society. America is showing very little sign, however, of wanting to change. As the affluent continue to push against subsidization and compensatory mechanisms requiring just a little more monetary support from those who can most afford it, the rift between the wealthy and everyone else continues to increase, and education continues to suffer.

A New Jersey parent, speaking of his daughter’s school, said he could easily “look in a classroom and know whether it’s an upper level class or a lower level class based on the racial composition.” This practice is commonly referred to in educational circles as “tracking” (as the candid term, being “segregation,” is undesirable). It’s an unfortunately common process in which students are divided into groups or classes based on their academic performance, a practice which takes center stage in The Wire’s fourth season.

A University of Colorado report bluntly states that while tracking is “rarely couched in the express language of race or class differences… the preservation of privilege is always the subtext” to arguments in favor of the practice. “You see kids entering the building through the same door,” the New Jersey parent said. Yet they enter a “second door,” he added, one that is systematically “stratified.”

When it comes to diversity in schools, as well as the rest of the country’s various institutions, these facts, as well as many others, make it very clear that the United States, though advanced and privileged in many ways, is still akin to a child who insists he wants a million dollars, but won’t admit upon receipt that he has no idea what to do with such a large allowance. The more progressive conservative, the moderate, and the neoliberal American may like the idea of diversity, but tend to get lazy or confrontational when they realize that such diversity demands from them compassion and empathy, not to mention study and understanding, and ultimately, a new perspective inherently critical of the free market, not to mention the monetary subsidization that will ultimately be necessary. While the privileged bicker about societal problems that have obvious and simple solutions (often requiring little more than a fair playing field, and some relatively minor tax increases), the oppressed minority wait, and suffer.

Despite these problems, the United States is still a popular immigration destination. Indeed, white Christians no longer make up the majority of the country, and the American public must ultimately learn to reconcile the uncomfortable fact that equality often means subsidies (see: always means subsidies), both fiscal and philosophical. Gollnick and Chinn succinctly argue: “A democracy expects its citizens to be concerned about more than just their own individual freedoms.” (p. 16)

Throughout the fourth season, Colvin does everything he can to help the kids assigned to him. Such is his nature, as he consistently chooses morality over other considerations. Predictably, however, his attempts at progress are ultimately cut short. This, among the most cutting critiques offered by the entire series, forces the viewer to understand that even in the educational system, and in practices meant to rear the youngest and most vulnerable, the systemic oppression is inherent: the American public school system administrators continue to reject reality, and the politicians writing the rules support them in so doing.

As we persist in the banal and useless implementation of sweeping legislation rarely backed by science nor approved by real experts (see: “No Child Left Behind” and “Every Student Succeeds”), the most vulnerable are inevitably “left behind” as they are given very little real opportunity to succeed. The only advantage to these legislative changes is that they present the appearance of effort on the part of those in charge.

If we’re ever to see real change in our schools, education reform must allow for equitable distribution of resources based on need, and backed by real science, rather than further swinging open the door for private interests. The hard truth, however, is that any progress toward that ideal seems an unlikely possibility thanks to the power of the education lobbies, not to mention the desire of those at the top to stick to the status quo.

Ultimately, as always, it’s up to us. If education and other societal institutions are left as they are, the overwhelming power of money will invariably be given precedent over the lives of real people with real need. The problem is the affluent who uphold the system. The victims of the system know it, and the only way to enact real change is a combined and active alliance of the citizenry against the likes of educational saboteurs like Betsy DeVos and her boss. Chaddha and Wilson write:

[E]ducation is regarded as the solution to social inequality. With an understanding of how unequal education reproduces social inequality, acceptance of the “achievement ideology” is a key mechanism through which existing inequality is legitimated. The entangled connections among these institutions are at the core of systemic, multigenerational urban inequality. (p. 186)

“Thin line ‘tween heaven and here” -Bubbles

Ultimately, as one of many institutions throughout the country beholden to private interests, the police force is just as culpable in perpetuating socioeconomic inequality, if not more so, than anyone traditionally referred to as “criminal.” As The Wire depicts, all gangs (including the police force) have rules and regulations, some written, some unspoken, yet known to the members of the clique and rigorously followed, while generally unknown to an outsider.

While the police force itself is targeted for critique throughout the show, an equally prescient message is that the individual officers, with some exceptions, are often decent people who are ultimately given little choice but to capitulate to the more regressive aspects of the system. Even as the force itself is aggrandized by the affluent and by “tough-on-crime” politicians as the institution principally charged with societal safety and ensuring justice, the officers themselves are often forced, thanks to impositions from those same politicians, to neglect the pursuit of that lofty task. Instead, true progress is rendered subordinate to the normal day-to-day operations of “the job” begrudgingly performed like any other 9 to 5: for little more than a paycheck. As Bunny explains:

Soldiering and policing, they ain’t the same thing. And before we went and took the wrong turn and start up with these war games, the cop walked a beat, and he learned that post… [S]tats, arrests, seizures, don’t none of that amount to shit when it comes to protecting the neighborhood, now do it? You know, the worst thing about this, so-called drug war, to my mind, it just ruined this job.

All the while, oppression is perpetuated, bodies pile up, and the truly guilty go free. Yet thanks to the politicians deceptively whitewashing the real effects of private money infused into police power, this government-sanctioned force, just as guilty of inhumanity as any group bearing the ominous title of “gang,” continues to enjoy the privileges of society’s praise, a society deliberately ignoring the boarded-up buildings conveniently placed somewhere in the periphery, just out of sight.

The system and its institutions have given society a paintbrush with which it has painted itself into a serious and unforgiving corner, as those of low socioeconomic status are given little choice but to fight against the very real oppression they face every day. The Wire tried to use this brush for something better: to paint as accurately as possible a picture of what is really happening.

As with any truly progressive effort, however, the question must be asked: to what end? For the middle class or the wealthy (indeed, the mirror points to many of us), The Wire is practically fiction. Such among us never experience life in the slums of Baltimore or other inner cities. Our significant power, therefore, is never employed in anything advantageous to those most in need. What’s left is simply gang warfare between the police and the drug culture.

These different cultures have become, in a way, tragically cherished. For these drug cultures, “the game” is often all they have, and they wear that badge, metaphorical though it may be, with great pride, at a level often unseen among those wearing the tangible badges. As the credits roll at the end of the final episode, we’re left wondering if there’s truly any point to making an effort for change. What can we do when such political power is entrenched behind the effort to keep the broken system exactly as it is?

The situation has become so ingrained, so complicated, that the mind behind this greatest of television offerings, David Simon, would be satisfied with even the tiniest amount of progress:

We bought in to a war metaphor that justifies anything. Once you’re at war, you have an enemy. Once you have an enemy, you can do what you want… I’m not supportive of the idea of drugs, but what drugs have not destroyed, the war on them has managed to pry apart… [So] the next time the drug czar or Ashcroft or any of these guys stands up and declares, “With a little fine-tuning, with a few more prison cells, and a few more lawyers, a few more cops, a little better armament, and another omnibus crime bill that adds 15 more death-penalty statutes, we can win the war on drugs” — if a slightly larger percentage of the American population looks at him and goes, “You are so full of shit” that would be gratifying.

Behind Simon‘s words, however, is the deeper message of his masterwork, a message that may be lost on the more casual viewer, but one that will be heard loud and clear by those who are paying attention. Throughout The Wire, the antihero protagonist Officer Jimmy McNulty is himself an example of one who would hear such a message. He’s something of an idealist, despite personal failings to which many of us may relate.

McNulty is the one most likely to say “You are so full of shit” to a superior, even in the face of criticism from others, including the wiser, but idealistically similar Detective Freamon: “The job will not save you, Jimmy. It won’t make you whole. It won’t fill your ass up… A life, Jimmy. You know what that is? It’s the shit that happens while you’re waiting for moments that never come.”

Inherent in McNulty’s character arch is the subtle suggestion that he is someone who can really make a difference; who despite deep character flaws has a sense of right and wrong that compels him to stand up to corruption. Indeed, McNulty is the only person that comes close to making any real change. So even as Simon is accused of being “the angriest man on Television” and a complete pessimist, still we find in his main protagonist a glimmer of hope, a plea to the flawed viewer, to those who are truly listening, who despite character flaws have a sense of right and wrong. So what can we do? We can stand up.

More effectively than any filmic expression to date, The Wire fulfills storytelling’s most fundamental purpose of societal critique. While it may be uncomfortable to realize, as Detective Freamon says, that “all of us are vested, all of us complicit,” even possibly prompting many viewers to turn away in favor of comfortable ignorance, still, The Wire perfectly places the responsibility for the problem, and ultimately, for finding its solution, squarely into our hands.

When do this shit change?

-Bunny

Do shows like The Wire help to contribute to social change? Why or why not? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Sources, Additional Reading

A Dictionary of Sociology. (1998). Colemant Report. Retrieved from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/coleman-report

A., R. (2011, February 17). Government of the rich, by the rich, for the rich. Retrieved from The Economist: https://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2011/02/political_economy

Alvarez, R., & Simon, D. (2010). The Wire: Truth Be Told. Grove Press.

American Immigration Center. (2015, March 11). US most popular Western destination for immigrants. Retrieved from American Immigration Center: https://www.us-immigration.com/us-immigration-news/us-immigration/us-most-popular-western-destination-for-immigrants/

Anderson, P. A. (2010, Summer/Fall). “The game is the game”: Tautology and allegory in The Wire. Criticism, 52(3/4), 373-398.

Bai, M. (2012, July 17). How Much Has Citizens United Changed the Political Game? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/22/magazine/how-much-has-citizens-united-changed-the-political-game.html

Beilenson, P. L., & McGuire, P. A. (2012). Tapping Into The Wire: The Real Urban Crisis. JHU Press.

Blumgart, J. (2011, September 2). 4 Ways Government Policy Favors the Rich and Keeps the Rest of Us Poor. Retrieved from Alternet: https://www.alternet.org/story/152284/4_ways_government_policy_favors_the_rich_and_keeps_the_rest_of_us_poor

Bowden, M. (2008, January/February). The Angriest Man in Television. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/01/the-angriest-man-in-television/306581/

Chaddha, A., & Wilson, W. J. (2011, Autumn). Way Down in the Hole: Systemic Urban Inequality and The Wire. Critical Inquiry, 38(1), 164-188.

Corkin, S. (2017). Connecting the Wire: Race, Space, and Postindustrial Baltimore. University of Texas Press.

Gass, N. (2015, November 23). Pew: White Christians no longer a majority. Retrieved from Politico: http://www.politico.com/story/2015/11/poll-white-christians-population-216154

Godsey, M. (2015, June 15). The Inequality in Public Schools. Retrieved from The Atlantic: http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/06/inequality-public-schools/395876/

Gollnick, D. M., & Chinn, P. C. (2013). Multicultural Education in a Pluralistic Society. Pearson Education.

Heick, T. (2017, June 10). ‘The Wire’ Crushed Public Education And We Weren’t Even Paying Attention. Retrieved from TeachThought: https://www.teachthought.com/pedagogy/the-wire-series-public-education/

Holt, K. (2016, 04 12). 14 Reasons The Wire Is The Best TV Show Of All Time. Retrieved from Screen Rant: https://screenrant.com/the-wire-est-tv-show-all-time/

Jameson, F. (2010, Summer/Fall). Realism and Utopia in The Wire. Criticism, 52(3/4), 359-372. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism/vol52/iss3/2/

Kois, D. (2004, October 1). Everything you were afraid to ask about “The Wire”. Retrieved from Salon: http://www.salon.com/2004/10/01/the_wire_2/

La Berge, L. C. (2010, Summer/Fall). Capitalist Realism and Serial Form: The Fifth Season of The Wire. Criticism, 52(3/4), 547-567.

Lee, V. E., & Burkam, D. T. (2002). Inequality at the Starting Gate: Social background differences in achievement as children begin school. Economic Policy Inst.

Levine, N. (1988). On the Transcendence of State and Revolution. In G. Lukacs, The Process of Democratization (pp. 3-62). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Love, C. (2010, Summer/Fall). Greek Gods in Baltimore: Greek Tragedy and The Wire. Criticism, 52(3/4), 487-507. Retrieved from http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/bitstream/handle/11693/38042/bilkent-research-paper.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Mathis, W. (2013, May). Moving Beyond Tracking. Research-Based Options for Education Policymaking. Retrieved from: https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/pb-options-10-tracking.pdf

Nellis, A. (2016, June 14). The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. Retrieved from The Sentencing Project: http://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

Quillian, L., & Lagrange, H. (2016, August). Socioeconomic Segregation in Large Cities in France and the United States. Demography, 53(4), 1051-1084.

Rothkerch, I. (2002, June 29). “What drugs have not destroyed, the war on them has”. Retrieved from Salon: http://www.salon.com/2002/06/29/simon_5/

Simon, D. (2011, April 1). The Straight Dope. (B. Moyers, Interviewer) Retrieved from https://www.guernicamag.com/simon_4_1_11/

Simon, D., & Burns, E. (Writers). (2002). The Wire [Motion Picture].

Stacy, I. (2015, September). What sort of novel is The Wire? Voice, dialogue and protest. European Journal of American Culture, 34(3), 161-178. Retrieved from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/ejac/2015/00000034/00000003/art00002

Strauss, V. (2015, March 30). Report: Big education firms spend millions lobbying for pro-testing policies. Retrieved from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/03/30/report-big-education-firms-spend-millions-lobbying-for-pro-testing-policies/

Talbot, M. (2007, October 22). Stealing Life: The Crusader behind “The Wire”. The New Yorker, pp. 150-163. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/22/stealing-life?verso=true

Telegraph. (2009, April 2). The Wire: arguably the greatest television programme ever made. Retrieved from The Telegraph: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/5095500/The-Wire-arguably-the-greatest-television-programme-ever-made.html

Yglesias, M. (2008, January 2). David Simon and the Audacity of Despair. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2008/01/david-simon-and-the-audacity-of-despair/47692/

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Digital Media Program Coordinator and Professor at Southern Utah University and Southwest Technical College; M.Ed.; Author at Labyrinth Learning and Film Inquiry. Passionate educator of film theory and history. World-class nerd with a wide array of interests and a deep love for many different fandoms.