There are movies that will leave you speechless, so overwhelmed with emotions and contemplations you find yourself lost in your thoughts for days. This is the power of Fran Kranz‘s Mass, a film whose beauty is in its characters. As it wields the art of dialogue, it becomes an intimate portrait of grief, pain, and forgiveness, each of its characters looking for their own absolution.

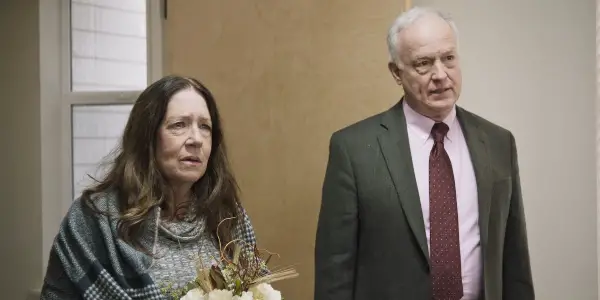

This is the movie of the year. Having premiered at Sundance earlier this year, Mass looks deep into the heart of grief, asking the hardest question of all – can someone be forgiven? I had the opportunity to speak with one of the film’s stars, Reed Birney about the tragedy of his character Richard, the emotional catharsis of Mass, and the individual perspective of grief.

Stephanie Archer for Film Inquiry: Hello! Thank you for taking the time today. I’m really glad this worked out. I also want to say congratulations on the film. It is absolutely phenomenal. I didn’t see it till last night and have been hearing about Mass since it premiered at Sundance. I hadn’t had the opportunity yet, but it’s been all my it’s been the must-see. You hear people talk about it, but you never realize how much people are letting you experience the film without telling you too much.

Reed Birney: That’s good, I think. Did you see it in a theater with people or at home?

I watched the film at home.

Reed Birney: I still haven’t seen it in a theater, so I’m really looking forward to seeing it with other people.

The emotional catharsis within that Mass – I would love to actually to see it the theater one night because I think the audience experience is going to take it to another level.

Reed Birney: I think so too. My wife saw it at the New York premiere with an audience and liked so much, even more than she had when she saw it on the TV. So I think you’re right.

I do have to admit, I’m still processing the film. There was so much to it in individual interactions of the characters, both couple and all four, and just the subject matter overall. So formulating questions were very interesting. What I really would like to ask was how did you become involved with the project?

Reed Birney: Fran [Kranz] wrote it with me in mind. I had known him in New York as an actor and we’d met socially and known each other since I think about 2012, maybe a little earlier than that. And I’ve been to see him in plays and he’d come to see me. And then in October of 2018, I got an email from him saying “I’ve written this thing. I don’t really know what it is. I don’t know if it’s any good, but I wrote it with you in mind. I’d be really flattered if you read it.” I read it that night and wrote him the next day, said I would go anywhere to do this with you. It was like reading Death of a Salesman. It was so complete and finished and nuanced and complicated for somebody who’d never written anything before. So it was kind of miraculous.

It’s beautiful. I mean the writing and the dialogue is just – it’s such a solid platform to build this experience of the film.

Reed Birney: I don’t know how he figured out how to make that conversation flow like conversations flow. It doesn’t feel writerly at all. To me, it just feels like the way people talk.

I was very surprised that it didn’t feel like a two-hour movie. Because you expect these four individuals are talking, it’s very heavy what’s being discussed and not discussed at the same time. And it was over before you had a chance to even process each part.

Reed Birney: That’s amazing that we’re just sitting at a table for two hours too, that, that, that it didn’t feel long. That’s great.

When both parties first meet, there is such a palpable tension and it’s there and it stays there and it just grows. Was that something that just grew organically between the four of you? Or is that something that you would maybe have rehearsed or had extra preparation for?

Reed Birney: We had two and a half days of rehearsal in New York, three weeks before we went to Idaho. So we had a little, and it was mostly like table work that you do in a play where you just ask questions and get to know each other. And then we had the three weeks to sort of let it percolate and showed up in Idaho. We filmed the goodbye at the end first. Which is weird not having filmed the conversation yet. And then they felt the ending before we filmed the sitting down at the table that I’m not in.

It was two weeks total in Idaho and we sat down and we had eight days to film the table. So it was really something. And we did about 10 pages a day until we got to the end when it got a little meatier and more intense, and then we slowed down a little bit, but it worked out perfectly and we knew we had to stop as soon as the sun went down because we couldn’t film in the room anymore without the sun.

The brightness in that room was so contrasting to everything spoken. That was incredible. I didn’t realize how much was natural lighting.

Reed Birney: Yeah, it was really essential. We were lucky it didn’t rain ever and it didn’t – you know, it was November of 2019 when we filmed it. So it was starting to be snow weather. We never had any snow – that would have spoiled stuff out the window. We were very lucky, really lucky.

You had mentioned that it felt like a stage play, and in a sense, you see that. There are moments where the characters start to finally move, to break free of this rigid almost box they have put themselves into. Was that choreographed or did all those movements come around organically?

Reed Birney: They were all planned by Fran when we were rehearsing those two and a half days. We did at one point, Fran said, let’s just read it and do what you want to do. And I got up earlier in that rehearsal and when we finished, he said, I don’t think you get up until later, which is when I get up in the movie. So he knew, just because he was so clear about what he wanted, he knew when it was absolutely essential that each character move away from the table. Jason Issacs’s Jay goes first. He goes and gets the water bottle. And then I think I might be next, or Ann might be next. You can probably tell me I haven’t seen it in a bit. So it was very purposeful.

I have to say that for Richard when you initially get to really take him in when they all sit down and they start exchanging and it gets further and further along with the conversation, he seemed very rigid, very closed, I think it’s even mentioned he seems kind of own that over this – like he has gone through the motions multiple times. But as you watch him more, there’s more to see – you see the grief and you see the struggle. How did you flesh out the character of Richard?

Reed Birney: Well, you know, Stephanie, honestly, it was all right there in Fran‘s script. The arc Richard was in there. I’m a wasp, so I think Richard was a wasp and I think he has a lot of the wasp – you know, we don’t like to talk about our feelings. We don’t like to share personal things. So this has been happening to him really for the last six years. He has been examined and parsed over and discussed. And I think it’s his worst nightmare. So he comes up, really comes into the room really with his Dukes up, I think. Like, I know what you think, I know what you say, what everybody says, and I don’t really want to be here. The first thing he says is I have to leave this afternoon. I think he’s there because he got talked into it and his lawyer and Linda thought it would be good. And I think he doesn’t think it’s going to be good. But you’re right. He has all this stuff that he just hasn’t dealt with. And I find him actually the most tragic character in the play or the movie because he doesn’t change. He doesn’t use this opportunity to get better. So he is going back to Baltimore in so much pain that he has no tools to deal with and no willingness to look at.

That’s one of the things I felt really read from the character of Richard is he was running, he was constantly running away.

Reed Birney: That’s right. He’s trying to hold on to any little shred of what his life was like before and that’s why he moved away and he’s near his other son, and he’s really – being with Linda is too painful to remember this thing. So he’s kind of just moving away from it. I think it’s not an accident that he shows up in a coat and tie, which is wasp armor.

I have to say costume design was very nuanced and stood out. Richard and Linda are put together compared to the parents who are still trying to put themselves together – Jay’s clothes were untucked and wrinkled. That’s interesting you said that about Richard’s suit because that really stood out. With Richard, a lot of his performance is not necessarily dialogue. There is a lot that you read off of him through non-verbals, like facial and body language. What were some of the challenges in capturing that?

Reed Birney: Well, um, you know, I personally think that listening is some of the most exciting acting I’ve ever seen, when I see people listening really well. So it’s important to me. I think it’s actually kind of important to all four of us. We know the power of listening. I just knew that the dialogue as the others were talking, there’s a constant dialogue in my head about hearing them, what do I think about that? You know, if I’m thinking the thought, then I’m assuming that it shows up in my face. So that’s really what it was, staying very active in the conversation. Jay says something I don’t like it, or Martha or Gail gets upset and that surprises me and moves me. So it’s really just staying in the room and active.

One of the things I really loved about this is that it’s teetering this fine line of calling for empathy and humanizing the parents of the shooter, that they’re just as much victims and they are grieving just as much. Coming from Connecticut, we have Newtown and constantly we remember the 26 angels. And in all actuality, there were 28. What was it like walking and balancing such a fine line within this project?

Reed Birney: Well, actually, the only real research I did was reading Adam Lanza’s dad’s essay on being a father of a shooter, which is beautiful and heartbreaking and very illuminating I think to a dad’s perspective. I’m going to work and I’m thinking everybody’s all right and all that. We decided and discussed that the movie really isn’t for us about gun control or even that event per se. It’s about how people deal with their grief and how they forgive each other and themselves and move forward. How do you make a connection that gets you out of the pain?

Richard doesn’t really do that, unfortunately, and that’s his great sadness. We were very aware. What we were dealing with is unimaginable to those of us who haven’t been through it. And I think we wanted very much to honor the people that have been through it, but not to presume that we have any kind of an answer about it, you know? So I think Fran specifically wanted to be these people. He didn’t want it to be some sort of, this is what people feel, you know, sort of like this is what these four people are going through.

And the for all four and they have their own way of expressing it. Jay tries to politicize it. Gail wants a reason, they should be telling me what happened. It’s about the four people, I think there is an immense amount that, even people who may not have experienced this, can relate to even in the themes of grief and redemption and forgiveness.

Reed Birney: Well, right. I mean, everybody has something they want to be forgiven for or somebody they want to forgive – that is a universal situation. So I think we were trying to be careful about not pinning it specifically to guns and gun control, because I think that misleads an audience reading about it because they think, oh, that sounds unappetizing. And I think it’s a much more universal one – honestly, in the end, uplifting and life-affirming story.

I completely agreed. So as I worked to formulate these questions, I found myself wanting to have a conversation more than just dictate questions and obtain answers. I have to say, I think that is the absolute beauty of Mass, its ability to be a platform for discussion. You don’t get often get that because a lot of films tell you what to feel or what to think.

Reed Birney: That’s right. Like they have all the answers and that I think what’s so beautiful about the movie is that there isn’t a sense of, this is the way. It’s really just like, this is how these four people dealt with this situation. And Richard’s not going to heal, Linda I think remains pretty shattered. But she’s touched some demon, I think, and maybe exercised some demon. And I’m hopeful for Gail and Jay in their relationship, that they can actually move forward in some way not to – she says it, she says, I was worried that if I forgave you, I’d forget Evan somehow – I find them incredibly moving the two of them.

A lot of times forgiveness is associated with moving on. So to give forgiveness if to potential leave whatever you were holding on to behind.

Reed Birney: I was reading an article on the Huffington Post yesterday about a man who lost his wife of 51 years. And he said I was unprepared for the grief. And he said I hate that phrase moving on. But I think what I want to say is forward. And I think that’s right. Because moving on does sort of imply leaving a loved one behind.

With all this experience, both being a part of the project and taking all of this away, what is something that you hope people will take away from the film?

Reed Birney: I really feel like the takeaway of the story and the message of the story, if you will, is that people have the power to heal and it takes a lot of courage, but when you want to, you can. And I think it’s incredibly brave of Gail and Jay, and even Richard and Linda, to come into that room after six years. It is hugely gracious. And that’s what’s required. It really requires a willingness to move forward.

As we are coming to the end of our time, it’s not so much a question. After watching the film, I found myself thinking Top of the Lake with Elizabeth Moss. In the first season, there is a quote from Holly Hunter’s character, “we don’t experience our deaths. The ones we leave behind do.” And I feel Mass truly emulates the idea of this, that even though Evan and Hayden have passed, it’s the parents that are left to work through these emotions.

Reed Birney: That’s right. I mean, everybody in that school was a victim. And then all their friends and teachers, everybody was a victim. But it’s a very special kind of grief when it’s your child. And so I think Fran really was interested in it because he thought he was a brand new parent when Parkland happened and he thought, I don’t know if I could forgive. And so he did a deep dive into reading everything he could about this and came up with this idea of this movie that really explores – is impossible to forgive? And I think the end of the day, I think it is. But it’s hard.

I think you’re successful in varying degrees. And I think you can – it’s like a scale you can forgive and not forget, or you can forget, you know what I mean? And again, my character Richard, I think really is so damaged and so broken by his shame and his rage and his guilt that he can’t, he can’t go near it. Just can’t go there. Even when he says, I regret everything it still feels like he’s in his head about it.

I completely agree. Do you have anything our readers can look forward to in the future?

Reed Birney: I am in Succession season three. I have an episode in that. I’m actually in Savannah, Georgia right now making a movie with Ralph Fiennes and Anna Taylor Joy called The Menu. It’s a wonderful script and I’m really having a thrilling time doing it. So that’s probably nine months or a year away.

I look forward to seeing it, of course. And thank you again so much for taking the time to talk with me today.

Reed Birney: Thank you for your kind words about the movie. It really means a lot.

Film Inquiry would like to thank Reed Birney for taking the time to speak with us today!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.