James Brown is known as the “hardest working man in show business.” But any summary of the career of Quincy Jones suggests the title should be his instead. The accomplishments of Quincy Jones are unmatched in the history of American music and popular culture. His abilities as a producer, composer, arranger, and performer are undeniable. And the sheer volume of his output is astounding. Equally impressive is the number of arenas in which he’s enjoyed success, including not just music but TV and film production, publishing, and philanthropy.

In counterpoint to his decades of success, Quincy Jones has lived a uniquely captivating life. Starting out on the South Side of Chicago in the 1930s, Jones was by his own admission involved in the gangs who then ran that part of the city, “carrying a knife and doing whatever [he] thought [he] had to do to survive.” As he tells it, this calculated outlook was a direct result of the fact his mother had been hospitalized for schizophrenia when he was just a child. He and his brother watched while “she kicked and screamed as they threw a straightjacket on her and carried her out.” For a time, he and his siblings lived with their grandmother, a former slave, who “cooked whatever she could get her hands on – mustard greens, okra, possums, and rats.”

In an effort to save his family from that poverty and strife, Quincy’s father moved them to Washington State, where Quincy played the piano for the first time, quickly taking up an array of other instruments before settling on the trumpet. It wasn’t long before he was playing in Lionel Hampton’s band, rubbing elbows with Count Basie, Clark Terry, and Miles Davis and becoming fast friends with Ray Charles. Over the next several years he would wield his musical talent and ambition as means to escape what may have otherwise been a tragic life.

Considering his origins, his struggle, and his accomplishments, the Netflix documentary Quincy is a missed opportunity. It takes a uniquely compelling story and turns it into something facile and, quite often, boring. In addition to its meandering through two overlong hours, it also ends up being maddeningly superficial, giving only the most cursory mention of several genuinely intriguing eras of Quincy Jones’ truly epic life.

Home Movies

Quincy was co-directed by Rashida Jones, who is also Quincy’s daughter, and Alan Hicks, a jazz drummer and documentarian. At last month’s premiere of Quincy, during the Toronto International Film Festival, Hicks said that their final cut sought to combine some 2,000 hours of archival footage with 800 hours of new material. Despite that ratio, the newer footage overwhelms the film, in which a chronological recounting of Quincy’s life is crosscut with a more contemporary narrative that, if it’s focused on anything at all, depicts its subject’s relentless lifestyle and the obstacles presented by age and health and hard living.

The opening minutes of the movie give a fair impression of how the rest of it will feel, starting with an impressive tour of the walls of Quincy’s home, featuring a smattering of the album covers and gold records to his name, as well as a sizable collection of photos with Quincy and celebrities A, B, and C through X, Y, and Z – from Duke Ellington to Paul McCartney, Frank Sinatra to Will Smith – before being interrupted by a brief but reverential podcast interview with Dr. Dre. And then it’s off again, through several more dizzying (and haphazard) minutes of “Q” Living the Life and hangin’ with Celebrities! – Michael Jackson and Tony Bennett and Willie Nelson and Lady Gaga and Lionel Richie and Bono and Snoop Dogg and Stevie Wonder and Michael Caine and…

All in all, the contemporary footage comprises a seemingly endless string of interviews, photoshoots, award shows, public appearances, planning sessions, business meetings, and on and on and on, during which the main purpose seems to be to show how many famous people are friends of Quincy Jones. There are Themes, of course, but from the start of the film nearly ten minutes go by before bothering with biography, and even then the narrative can only stay focused for two or three minutes at a time before jumping back into the mania of the present day.

That’s a shame, because the biography is more compelling. It’s also delivered more successfully than the rest, held together largely by Quincy’s narration, which strikes a precarious balance between scripted and sincere. But Quincy keeps getting in the way of itself, apparently never tiring of its impulse to impress. The biography, meanwhile, is not the only thing that gets short shrift. Quincy’s music too is relegated to the background, while the musicians and other famous people get all the attention.

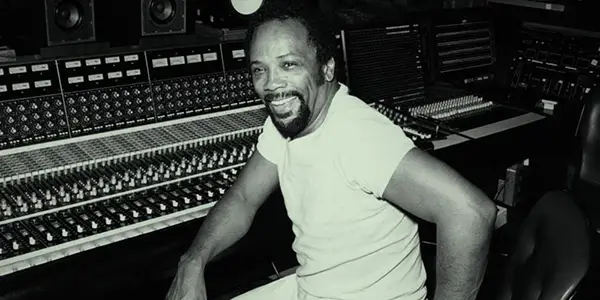

It can be a thrill to hear a few bars of “Summer in the City” or “Pleasingly Plump” or “Soul Bossa Nova” or any one of the many songs that you will probably recognize but may not know were written by Quincy Jones. Unfortunately, Quincy has next to nothing to say about how any of this music was created. For a documentary about one of the most important composers, arrangers, and producers of the last six decades, it spends a bafflingly small amount of time in the studio. Quincy is overall a film more for fans of celebrity than fans of music or, for that matter, for anyone interested in a complete portrait of this fascinating human being.

So, if it’s just not that kind of documentary, what kind is it? The following assessment is reductive (and a bit unfair), but there’s a persistent feeling that Quincy is an extravagant home movie, made by and for and of the rich and famous. It’s the sort of cinematic portrait you might make if you were the director and the subject was your father. But, again, that’s not entirely just. Especially considering that there are some genuinely intimate moments in the film, and that most of them involve interactions between Quincy and Rashida.

Though, as a subject, Quincy never seems truly relaxed, like he’s let drop the safest version of his public persona, there are a few moments when he dispenses pearls of honest-to-god wisdom. When Rashida asks him how to “deal with ego in your art,” his reply is deep, and deeply felt: “Ego is just overdressed insecurity.” He tells her, essentially, to dream so big that there’s no room left for ego, so much so that you’re trying so hard to fulfill your impossible dreams that you don’t have a chance to think too highly of yourself. It’s one of a handful of moments in the film that show Quincy as genuinely humble and deeply wise, despite the fact he’s not exactly perfect.

Behind Every Great Man

Quincy is, like so much of his music, remarkably self-assured, effortlessly cool, and so very, very sexy. He is also astonishingly prolific, and not just musically. Over the last half-century or so he’s had seven children with five different women. He’s been married three times; only one of those marriages lasted longer than ten years.

Early in 2018, in a sensational GQ interview with Chris Heath, Quincy claimed that he currently has over twenty girlfriends, veritably stationed at exotic ports of call throughout the world. He also explained that his daughters have given him “new numbers,” referring to the age range they consider acceptable for their 85-year-old father’s female companions: 28 to 42. (Notably, on the higher end, still one year younger than Q’s youngest daughter.)

It’s not that the documentary doesn’t acknowledge any of this. It’s there, in one way or another, to one degree or another. But it also doesn’t dig in, for better or (mostly) worse. When Jeri Caldwell, Quincy’s first wife, details the breakup of their marriage, including her husband’s many infidelities, and flatly states that “He grew in ways that I wasn’t growing,” it’s hard not to be disappointed that the film leaves such a significant, and telling, statement unexplored.

Peggy Lipton, Quincy’s third wife and mother to Rashida, a gifted actress who became famous from her role on The Mod Squad but has more recently portrayed “Norma Jennings” on Twin Peaks, put her own career on hold for nearly a decade to support her husband. She too is treated as no more than a supporting character in Quincy’s narrative. There is virtually no discussion of what Lipton and Caldwell and the other women in Quincy’s life gave up so that he would be able to pour himself so completely into his work (and play!), and the film is so much less credible because of it.

Breaking Barriers

There are other holes. As a wildly successful black man in America, Quincy Jones broke a number of racial barriers and faced a lifetime of discrimination. For a time he was the only black film composer in Hollywood. Contemporaries like Truman Capote doubted, out loud, that a black man could even be capable to do the job. Of course Quincy was capable. More than capable.

He’d taken his considerable talent to Paris, where he studied composition with “the queen of classical music,” Nadia Boulanger, who was mentor to a staggering list of great Twentieth Century classical composers, including Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Igor Stravinsky. Once again, when Quincy refers in the film to his time with Boulanger by saying that “France made me feel free as an artist and as a black man,” but then does nothing to elaborate on this remarkable statement, it can only be seen as a loss.

And it’s not the only one. A later sequence deals briefly with Quincy’s tenure with Frank Sinatra and Count Basie in Las Vegas. At that time, in 1964, Vegas was “mob territory” and deeply racist. As Quincy remarks, “No black entertainer in their right mind would wander around those casino hotels alone.” The black performers were forced to eat in casino kitchens and sleep in the “black hotels” in another part of town.

Sinatra demanded that his black colleagues be given better treatment. If not, he threatened not to perform. In response to this we hear Sinatra say, simply, “Suddenly it changed. And I can’t explain to you what happened.” He can’t explain? Or he won’t explain?

Either way, that’s the end of the discussion. Of course, archival material doesn’t allow for follow-up questions. Still, how can you see this as anything other than a disappointment? Either one of these episodes would make for a compelling sequence in a Quincy Jones biopic, especially in America in 2018. But in this doc they’re just not given time.

Ghetto Gump

In the end, is that all it is? Is it affectionate hagiography, or is there just too much ground to cover? One of Quincy’s nicknames is the “Ghetto Gump,” owing to the implausible number of famous people he’s crossed paths with and incredible situations he’s found himself in. Even though Quincy seems preoccupied with its subject’s many, many famous friends, their existence is an inescapable facet of his persona.

Nonetheless, that 2018 GQ interview parades Quincy’s celebrity encounters in front of the reader in a way that’s much more illuminating than it is simply voyeuristic. Its vignettes with Marlon Brando, Malcolm X, Pablo Picasso, Prince, and so on are not just great stories. They also shine a light on who Quincy Jones is and what’s important to him. It’s more than sensationalism. It’s a very well crafted, very compelling portrait.

It’s not hard to understand why someone, especially someone so close to the subject, might see that sort of thing as gratuitous sensationalism. But Quincy Jones, in addition to his talent and his accomplishments, is a truly sensational human being. Leaving that out means the picture is incomplete.

What are your favorite cinematic portraits of people who are or were larger than life?

Quincy was released on Netflix on September 21, 2018.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.