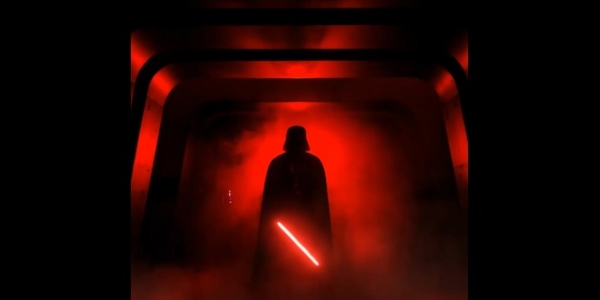

As I watched the last few minutes of Star Wars: Rogue One in the theater on its opening weekend, I felt a profound unease as the crowd cheered at the appearance of Darth Vader. He cut through a dozen or more rebellion soldiers with his lightsaber. He used his mastery of the force to make mince meat of the individuals who stood in his way. It was an awesome display of his power.

Cheering the Bad Guy

But despite his ultimate redemption at the end of the original Star Wars trilogy, his actions throughout were those of the villain. And here, he was in full power and glory, using his power to cut through the good guys like a hot knife through melted butter. It was a powerful tie-in to the original film, A New Hope, but it felt hopelessly at odds with the rest of the film I had just seen. And I couldn’t shake the question, why was the crowd cheering the bad guy?

I don’t think it was because they were anticipating his eventual redemption. I think it was because they enjoyed seeing this figure, around which two trilogies of films were built, exercise his full power. It didn’t matter to the audience that he was the bad guy. That he was the very thing the heroes of Rogue One were fighting against. That he was crushing and killing individuals who had hopes and dreams and passions but put them aside to join a cause to allow others the hope of living them.

But I’m not here to talk about Star Wars. I am here to talk about the appearance of cool and the Quentin Tarantino Problem.

Tarantino: The Appearance of Cool

To say that Quentin Tarantino is a polarizing figure in modern cinema is an understatement. His films have inspired a generation of filmmakers and ostracized a section of film viewers who struggle to stomach the content of his films. And the brewing tension has manifested in a rubbernecking response to his next announced film, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, a story about an actor played by Leonardo DiCaprio and his stunt double played by Brad Pitt trying to make a career breakthrough during the Charles Manson murders. Real world concerns involving Tarantino’s relationship with producer Harvey Weinstein, the original focus of the #MeToo movement, and his treatment of actresses like Uma Thurman (Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill Vol. 1 & Vol. 2) have added fuel to the fire.

Tarantino, whose B-film influences aren’t so much worn on his sleeve as held as standard bearers, has made a career about making villains look cool. They may die ignobly, as Vincent Vega (John Travolta) did in a bathroom in Pulp Fiction, or with cathartic violence like Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) in Death Proof, or even accomplish their goals like ATF agent Ray Nicolette (Michael Keaton) in Jackie Brown. But they are all written with a panache that frames the lives they live as unapologetically cool.

Like so much of the Blaxploitation, revenge epics, Hong Kong action and martial arts films, Spaghetti Westerns, and B-movie pulp serials that Tarantino draws from, his films invariably craft narratives around the underdog. Ostensibly, his heroes are the put-upon, the disenfranchised, the minority, who get their justice by the end of the film. There are even elements of hope, or nods to something like a greater power in the universe.

Notably, in Pulp Fiction, Samuel L. Jackson’s hitman Jules leaves his life of crime after what he describes as a miracle that saved his life, or the contents of the briefcase he and Travolta’s Vincent Vega are tasked with recovering (some critics have likened its unseen glowing contents to the contents of the Ark of the Covenant from Raiders of the Lost Ark). And then there is the slow opening credits zoom out from a crucifix planted along the side of the road in his The Hateful Eight—a symbol of redemption anomalously placed in stark contrast with the rest of the film? Yet any nods to a greater moral authority or catharsis in eye-for-an-eye justice are undercut by the continued pattern we see in his work: an emphasis on smart, sophisticated, witty cruelty.

They say the pen is mightier than the sword, and while Tarantino has gotten a lot better at choreographing and filming action scenes as his career has progressed, it’s undeniable that his main and lasting appeal remains his dialogue. What Star Wars fans expect from Darth Vader, Tarantino fans have come to expect from his sordid assortment of villains and anti-heroes. What are the scenes you remember from his films? Mr. Pink’s (Steve Buscemi) screed about not tipping waitresses from Reservoir Dogs? The burger royale with cheese conversation as Vincent and Jules go to perform a hit from Pulp Fiction? Hans Landa’s (Christoph Waltz) opening scene in Inglorious Basterds? Samuel L. Jackson’s revenge story on Bruce Dern’s son in The Hateful Eight?

What is Most Unsettling

These moments all range from willful disregard of other’s lives to flat-out genocide. But if Tarantino’s goal is to display the ultimate banality of these evils, his way of getting there firmly establishes the machismo, power, and cool of the characters every step of the way. But maybe the problem is with an audience that believes this façade is cool. Most of Tarantino’s famous monologues and exchanges are the type of dialogue someone who has not actually suffered or struggled or engaged the world might think is somehow insightful or a display of strength.

Mr. Pink can wash his hands of responsibility to tip waitresses by saying it’s the system’s fault, but would he feel that way if he was the one who had to wait tables? And does he have no responsibility to oppose an unjust system? Vincent makes one discovery about a different culture and just gets stuck on it—gaining no true insight—treating it as if it were something more than just an observation. Almost every plot point in Tarantino’s films is treated as a thought experiment rather than a circumstance that affects real people.

We see this detached privilege in Pulp Fiction when Bruce Willis’ Butch turns back to save Ving Rhames’ Marsellus from a couple of rapists. While ostensibly the plot point is Butch doing the right thing and saving his former enemy, what happens is an extended sequence of Butch selecting, discarding, and selecting a new, cooler weapon with which to fight—all the while hearing Marsellus’ screams in the background. The plight of the character, of the person, is secondary to the coolness of the weapon used to save them. This theme is echoed in Django Unchained, where Christoph Waltz’s Dr. King Schultz shoots Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie only at the point he feels disgusted by the man, “unchaining” Django (Jamie Foxx) only when he was good and ready.

Tarantino has an undeniable ear for dialogue, and sense of how to mash up diverse influences. But whether he’s writing a scene for himself to use the N-word as many times as possible in Pulp Fiction, or putting an actress in physical danger (Uma Thurman, while filming the Kill Bill films), or giving a Nazi character a seventeen-minute tour de force cold open in Inglorious Basterds, it’s not clear he’s using his considerable talent for anything other than making the audience cheer for the bad guy. Will we be encouraged to cheer on Charles Manson in Once Upon A Time In Hollywood? The prospect is unsettling.

What are your thoughts on Quentin Tarantino?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.