QUEEN OF HEARTS AUDREY FLACK: The Art, The Artist & Vanitas

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies…

Her name sounded so familiar. I tried to jog my memory and dig into the inner recesses of my mind. Audrey Flack. She painted…Marilyn. As in Marilyn Monroe but not like Andy Warhol‘s assembly line pop confections. Photorealism. Warm and wafting with nostalgia. That was it.

It shows the dearth and deterioration of my art history knowledge or maybe it’s indicative of our broader culture. We have a habit of equating artists to one or two token pieces and using them as a heuristic to begin defining and conveniently compartmentalizing their entire career. They cease to be artists and only another name and date we stash away for a rainy day or a round of Jeopardy. I’m as culpable in this pervasive cultural triviality (if you pardon the expression) as anyone else.

Given the state of things from my often oblivious perspective, what a delight it is to rediscover Audrey Flack not as a solitary piece of work in my art history textbook but a living, breathing artist of groundbreaking pedigree who is still in the throes of the creative process to this very day.

Because artists are driven by a kind of compulsion to create that scorns the markers of the world-at-large – including my well-meaning textbook. What a revelation to see her works in a gallery with new eyes – coming to appreciate the personality and the person behind the paintings more fully.

Getting to Know Audrey Flack

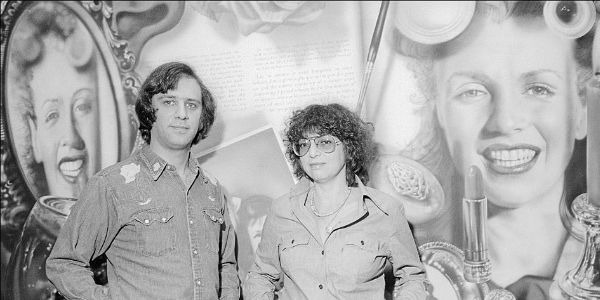

At 88 years young, she is an example to us all and what’s refreshing about Deborah Shaffer and Rachel Reichman‘s look is how intimate and personal it feels, grounding a remarkable woman in a very personable and extraordinary light. As she works on a reimagination of one of Peter Paul Reubens’s works, superimposed with Superman and Supergirl, she notes the “flesh and jewels” filling up the canvas.

Why is she still at it more than 50 years since she first took pen to paper? In her own words, art cuts across time. We need art to deal with our mortality. If she’s speaking for herself than her words hold true for all of us.

At first look, from what I can remember of her oeuvre, it seems like a grandiose statement. More on that later. For now, we are given the formative details of her adolescent life. A mother who gambled, a father she loved dearly dying unexpectedly, and then her discovering of art as an outlet and a way for her to make sense of the world. Her childhood recollections are still very much inbred into bygone remnants of New York City.

She has a lovely interaction with a precocious young girl who is curious about how she managed to paint canvasses so big. What a pleasant reminder it is. Because through the mediation of this documentary, we have the wonderful ability to actually be able to commune with an artist and get their own feedback and build off one another in this manner. After all, this is what art is for, creating a kind of symbiosis between creator and audience.

After all, this is a woman who knew the art world at one of its creative peaks with abstract expressionism, including the likes of Jackson Pollock (you know him), Kline (I had to look him up), and De Kooning, among others. They were her associates, her peers, and her friends.

She’s not only living, breathing history, but she acts as a guide, seamlessly explaining the evolution of art — the depiction of objects within space — jumping from Giotto’s Frescoes before the Reinassaince to Cezanne to Cubism, all the way to Pollock, a man who essentially shattered the accepted paradigms. It’s only through her dissection and resulting reverence, I have cause to appreciate him more than I ever did before. I consider it a gift.

She proved an up-and-coming star up the art world at the renowned Cooper Union while also gaining a scholarship to Yale under the tutelage of Bauhaus architect Joseph Albers. Her recollections of the man and the masher shed light on the uncomfortable misogyny that is a through-line in many of the personal stories of pioneering women. The resounding truth is Flack’s assertion, “You’re never the only one.”

Despite her isolation as a woman in a predominately male-dominated world and the inherent toxicity therein, somehow her creativity was still nurtured and fed. As she notes, “Nobody can take your creativity away from you” and hers was cultivated by practice and exposure to many things, including, interestingly enough, biblical iconography from the masters.

Strength in Hard Times

As the documentary plots the course of Flack’s life, her success is made evident to be even more extraordinary. Even as she looked to forge a career following her father’s death, she entered a marriage with an absent first husband and struggled to care for her beloved daughter, who would have been diagnosed with autism if doctors knew about it.

This was one of the tough periods of her life and yet in the midst of the isolating hardship, she never stopped painting, never stopped drawing, because as her childhood friend puts it so eloquently, these things were “her heart and soul.”

However, even in the close-knit artistic community, she was immersed in, friends turned on her for her prolific use of photographs to paint from. It didn’t matter she did it partially out of necessity as a busy mother who couldn’t carve out hours to devote to a single still life. Regardless, it was deemed that she, along with other creative harbingers like Chuck Close (also found in my high school textbook), was tainting art.

Out of this development, her paintings continued to evolve to reflect the cultural moment she was experiencing in the early 60s. For me, these were some of the documentary’s most eye-opening discoveries. The paintings during this period are historical, political even, but they express with grace and clarity human emotions and events that were occurring. Whether it was nuns marching for civil rights or Mr. and Mrs. Kennedy riding in the motorcade minutes before the president was shot, Flack captures them with a lucid candor.

The film also proves a fascinating eye into her very unique creative process. Flack eventually transitioned from small black and white photos to using slides projected on a canvass and painting over the image, texturing the process with spray paint and layers of colors, to draw out the illusion of natural light on a reflective surface.

These images of everyday artifacts whether perfume, cakes, or other trinkets became emblematic of her career (certainly for novices like yours truly). You can take them one of two ways. There’s an obvious lavish decadence to them. They feel ephemeral, superficial, and far from being realistic, the paintings have a silted visual perspective.

However, Flack’s acknowledgment of Biblical iconography teases out the other elements of her works, making them equally fascinating, because she purposefully blends these artificial images with the symbolic memento mori-like still lifes of traditional European canon. These of course come from the Latin phrase meaning “remember you must die.” They historically featured skulls, flowers, and other signs of life and death as a symbolic expression of the transience of life. Something clicked right there.

Vanitas

When I first learned about Marilyn, it took up a measly page out of a textbook. Seeing this sprawling work stretched across the wall realigned all of my perceptions of this piece of art. In many ways, this doc functions much the same, enlightening and increasing my estimation of Audrey Flack.

Because Marilyn was always such a striking counterpoint to Warhol’s depiction of the icon as a flashy pop culture screen goddess. It’s as if Flack gives Norma Jean her life and identity back to her, celebrating her life in a more pensive, thoughtful, and delicate manner. It’s the Marilyn one gathers was buried under there beneath all the glamour and fame.

The painting also comes with the parentheses “Vanitas.” Strange. I never noticed it before, but it makes so much sense. Again, it’s closely tied to this European artistic tradition of “Memento Mori.” In the book of Ecclesiastes, there’s the oft-quoted line “vanities of vanities; all is vanity.” Essentially, life is often pointless; it’s chasing after the wind. Despite all our striving in between, we’re born and eventually, we’ll die. Flack knows it too. She mentions early on art is how we get in touch with the immortal and this is a precise expression of that.

I’ll never look at Marilyn (Vanitas) the same way again. It’s now imbued with some much more meaning — almost religious in context — but also deeply personal. A tribute to a candle in the wind.

Queen of Hearts Audrey Flack: Conclusion

What are the takeaways of Queen of Hearts? It’s the fact Audrey Flack is still constantly curious, reinventing herself, and following her passions. Not the market, not the derision of the critics, and not the commercial tides of the times. As it should be. Thank you for bringing so much beauty into this world and putting it in a space so we could all enjoy it together. Again, as it should be.

There was one final pertinent reminder evoking Shakespeare. Rather than comparing herself to the bard, Flack touches on something universal about him. All great art is for the people. For the cultured elites with their furious quills and salons and equally, even more emphatically so, for the common folk who have their own barometer to gauge genuine authenticity. It’s not going out on a limb to affirm Audrey Flack’s art does exactly that. It’s for all people. There need not be a finer compliment than that.

Have you ever heard of the work of Audrey Flack? Would you agree that great art is for all people? Let us know in the comments below.

The film will have its premiere at DOC NYC on November 9th. Get tickets here. Find out more about the film here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies with him. Follow his frequent musings at Film Inquiry and on his blog 4 Star Films. Soli Deo Gloria.