THE PHENOM: A Drama With Daddy Issues

Former film student from Scotland turned writer and film reviewer.

The Phenom is a difficult film to pin down. While trailers and taglines suggest a sports drama in the vein of, say, A League of Their Own or For The Love of the Game, this somewhat sombre drama feels tapered down, unwilling to pander to the feelgood melodrama that can sometimes overwhelm these kind of movies.

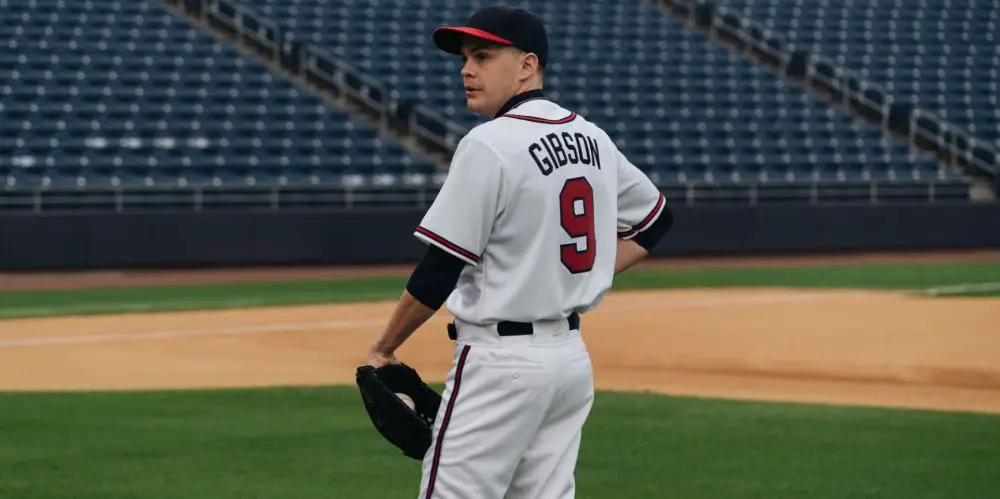

It’s the story of the improbably named Hopper Gibson (Johnny Simmons), a talented pitcher thrust into the limelight after signing for a major league club straight out of school. Gibson seemingly has it all: a smart girlfriend (Sophie Kennedy Clark), a burgeoning career, the ability to, as his teacher points out, ‘earn more money than I will in all my lifetimes,’ and yet when we first meet him he’s in a therapist’s office grudgingly pouring over video footage of himself pitching and trying to understand where it all went wrong.

Hopper, you see, had a serious case of the yips and struck out badly enough during a game – five wild pitches in one inning we’re told by the disembodies voices of television sports analysts – that he was pushed down to the minor leagues.

His club, in an effort to protect their investment, have him see a dedicated sports psychologist, (a reliably solid performance from Paul Giamatti in the kind of aloof intellectual role that is his bread and butter in Hollywood) and the young man reluctantly plays along.

While impressive, and extremely well acted, there are certain niggling things about The Phenom that make you feel the film had the potential to be much more than the end result.

Ethan Hawke Like You’ve Never Seen Him

Almost from the beginning Hopper’s father (Ethan Hawke) is a spectre floating above his son’s head, from the initial meetings with Giamatti’s therapist to the tentative discussions with his baseball coach, a man keen for Hopper to avoid his father’s self-destructive tendencies.

So when we first see Hopper Sr. lying on the couch as his son enters the room we are already well aware of his violent potential. It’s here that the film seems to find its anchor. While Hopper Jr. can be very difficult to relate to, and harder still to read, we’re never in any doubt he’s driven by the fear of his father.

Ethan Hawke prowls menacingly on the edges of the screen, ready to explode into rage at any moment. Whenever he and Hopper Jr. share a scene, we’re never comfortable, knowing that anything could happen.

Hawke has played unsavoury characters before – and recently impressed as the down-at-heel Chet Baker in Born to be Blue – but here he portrays something of an unusual role for him. Hopper Sr. is a man turned bitter at the mediocrity of his own life.

A wannabe pitcher in his own youth, his penchant for drugs and reckless abandon saw him strike out and turn to small-time criminal enterprise. He passes the wreckage of his dreams to his son, and soon becomes the darkly authoritarian presence behind Hopper’s fears. Covered in tattoos and sporting a buzzcut, Hawke plays Hopper Sr. like the archetype of working class middle-American men: he’s lazy and unkempt but full of rage.

An early scene sees him force his son to run suicides for the crime of smiling to the camera (“no emotions on the mound”) and at first he’s barking orders from the edge of the frame until suddenly he bursts forwards, chasing Hopper Jr. across the driveway like a pitbull, barking into his ear.

The framing of that scene is typical of the film. It’s not quite conventional, and can occasionally be jarring. Dialogue, for instance, can take place without the traditional cutting back and forth between characters. This leads to a lot of reaction shots, and dialogue being spoken off camera. It’s a stylistic choice, but a confusing one as we’re expecting to read the character’s face as he’s speaking, rather than the reaction of the person he’s speaking to.

Imagine, for example, you were standing talking to two people. You’re looking at one of them as he is speaking – naturally – and when he’s finished and the second person starts to speak, you just continue to look at the first person. It’s awkward and unnatural.

It fits in well with the rest of the scenes, however. Director Noah Buschel allows his camera to linger just to the point where you start to feel uncomfortable, sure that the prolonging scene means something sinister may occur.

Most of the time you’ll be wrong, with the exception of a later incident at a hotel involving a deceptive young woman; the scenes play out long enough to give a sense of weight to them. Rather than cutting quickly to important moments, The Phenom slowly and steadily builds up to them, creating an air of suspense that it doesn’t always seem to know what to do with.

More Ordinary People Than Field of Dreams

The Phenom could have gone down the path well trodden by previous sports movies, but what’s different here is that you rarely ever see Hopper play baseball. There are moments where he trains; he pitches to a crowd of coaches holding speedometers to test the speed of his throw, he stands at the mound watching a flock of geese overhead, and occasionally we’ll see him with his coach, but the game of baseball is not this film’s focus.

Instead, Buschel seems more interested in the idea of success and isolation. The Phenom obviously wants to be more Ordinary People than Field of Dreams. Hopper argues with his girlfriend because he feels she can’t possibly understand the pressure he’s under; his therapist, the youngest sports psychologist ever to be hired by a major league team, struggled with alcohol after one of his charges committed suicide; Hopper Sr. is haunted by the success he craved and forces his dreams on his son.

At one point, as though underlining the filmmaker’s message, Hopper’s girlfriend launches a polemic against the idea of celebrity in America. “Worshipping these false American idols, and people just buying into this Harry Potter syndrome, like wanting to have a f*cking lightning bolt on their forehead,” she growls, “do you really believe in any of that? Because nobody is more special than anyone else.”

Giamatti, it has to be said, is underutilised here. His brand of insightful observation is perfectly suited to a film about the internal struggles that go hand-in-hand with sports stardom. You feel like the film really starts to take off during their sessions to the extent where there is a whole other film to be made, which, you suspect, would be much more interesting – like an offbeat Good Will Hunting. However, here he is oft relegated to plot point in order to drive home the cliche of hypocritical therapists praying on the insecurity of celebrities.

Surely if this film will be remembered for anything, it’ll be for Hawke’s dangerous performance – he is aptly described as a time-bomb at one point – and as Johnny Simmons‘ breakout role, for he will almost certainly go on to bigger things.

Conclusion

The Phenom does a good job of dissecting the idea of success and fame, and contrasting that with failure and mediocrity. It’s also powered by solid performances, primarily from Hawke and Giamatti, but ultimately it doesn’t reach its potential and leaves you feeling not quite satisfied with the result.

While The Phenom purports to be a sports movie, it’s not quite in the ranks of the greatest sports movies of all time. What would you say is the best sports movie?

The Phenom will be available on DVD and Blu-Ray August 30, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMWgk9mRX6k

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.