More than 45 years after the death of Franco, Spain still bears the scars of his brutal dictatorship. One of the many ways in which these scars take form is through the unmarked mass graves that litter the countryside. After decades of being ignored — as if by forgetting Franco’s victims, his violent regime could also be forgotten and left behind to dissolve into dust — these graves are now being exhumed so that the victims’ grieving descendants can rebury them properly and finally, hopefully, find some form of peace.

This dark period of Spain’s past and the long-overdue attempts to come to terms with it in the present are the subject of the new film from iconic Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, who believes that the Spanish Civil War will not truly end until all of these graves have been opened. In Parallel Mothers, two women who give birth at the same time in the same hospital find their fates intertwined; one of the women is simultaneously working to have her great-grandfather’s body exhumed from the mass grave in which she believes he lies. In exploring their attempts to create an altogether modern type of family in the looming shadow of the past, Almodóvar reminds us that without truth, openness, and honesty, one can never truly move on from tragedy.

Buried Secrets

Janis (Penélope Cruz, in her seventh film for Almodóvar) is a successful photographer in Madrid who enlists the help of one of her subjects, a ruggedly handsome forensic anthropologist named Arturo (Israel Elejalde), in getting a mass grave in her hometown exhumed so that she can finally lay her murdered great-grandfather to rest. Their working relationship quickly becomes a romantic one, and soon, Janis finds herself unexpectedly pregnant.

As a professional woman of a certain age, Janis sees this as her one chance to become a mother and has zero regrets, even if her baby’s father is a married man who cannot play a traditional role in their little family. However, the young woman who shares her hospital room, Ana (newcomer Milena Smit), has a far less positive outlook on motherhood. Fortunately, Janis provides Ana with the support that Ana’s mother, Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón), a middle-aged actress finally finding the success onstage that she has dreamed of her whole life, cannot provide. Like Ana, Janis knows what it is like to feel motherless; she was raised by her grandmother after her father disappeared and her hard-partying young mother (who named her daughter after Janis Joplin) died.

After the two women give birth to daughters on the same day, Janis and Ana are bonded by the experience, and exchange phone numbers so they can stay in touch. But amidst the joys of motherhood, some small concerns start to bubble to the surface. No one thinks that Janis’ daughter looks anything like her, and Arturo denies that the child could be his after getting one glimpse of her. Wanting to stomp out the sparks of doubt before they can catch fire in her heart, Janis gets a DNA test. And as this is Almodóvar, you can probably guess what the results are.

The cast of Parallel Mothers is rounded out with some Almodóvar favorites, including the delightful Rossy de Palma as Janis’ best friend, Elena. And naturally, even as Janis’ life spirals out of control, her glamorous apartment remains a marvel of color and design — it wouldn’t be an Almodóvar film otherwise. With walls painted bright reds and blues and accented by the most perfectly chosen artwork and knickknacks, courtesy of set decorator Vicent Díaz, it’s a joy to look at even as the characters within it start to crumble.

Beautiful Lies

As the undisputed heir to Douglas Sirk’s throne as king of the lavish melodrama, it’s hard to imagine a filmmaker better suited to steering such a wildly emotional and occasionally outrageous narrative as Almodóvar. Even when the plot takes a turn into telenovela territory with its surreptitious DNA tests and surprising sexual encounters, Almodóvar ensures that it all finds a basis in real, human feeling. The parallel storyline involving the exhumation of the graves and the pain felt by Janis and so many other descendants of these crimes—left unspoken for so long due to their fear and the government’s purposeful forgetfulness — adds further authenticity to the drama, grounding these women’s personal trials and tribulations in the history of an entire nation.

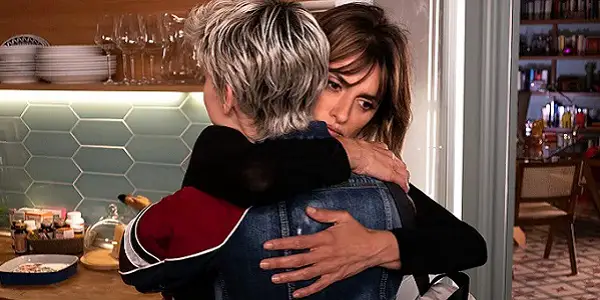

The relationship between Janis and Ana is one between two women that at first seem to have little in common, apart from the time and place in which they both gave birth, yet the ties that bind them are strong, true, and deeply compelling. Ana doesn’t understand Janis’ preoccupation with the past, being of a generation so far removed from Franco that his crimes are barely more than whispers passed between relatives; Janis cannot comprehend a world in which Ana and her generation don’t acknowledge the horrors that their country went through, for remembering them is the most important way of ensuring they never happen again. Both women, however, know what it is like to grasp for any remnants of love and family they can find and do so with each other.

The relationship between Janis and Ana, while it does turn sexual at one point, cannot be easily labeled as a lesbian love affair, for their intimacy contains a multitude of layers beyond (but including) physical attraction. When Ana leans in for a kiss after the two women have been drinking, Janis’ first reaction is one of shock, then one of a lioness going into survival mode; she’ll do whatever it takes to protect and preserve the strange little family they’ve put together. It’s nontraditional, flexible, and not defined easily by genetics, but it is a family nonetheless—one that is altogether modern and based on mutual love. Yet the secret that Janis carries deep inside her cannot stay buried for long, and the contradictions inherent in the way she is living her life — seeking the truth about her great-grandfather’s death while holding onto a lie about her daughter — are guaranteed to get the better of her sooner or later.

Cruz gives what might be her greatest performance as Janis, a complex woman whose attempts to solve the problems in her life only spawn additional problems. Cruz is aging gracefully in a way that somehow makes her earthy natural beauty even more compelling if that were possible. But of course, she is never more beautiful than when photographed by Almodóvar and his regular cinematographer, José Luis Alcaine, who focus on Cruz’s face and figure both for their undeniable aesthetic qualities on screen and the way she uses them as an actress; they have always known how to emphasize her assets without exploiting them. As you watch Janis juggle the lies that start to pile up in her life, frantically worried that one slip-up will cause her to lose everything she holds dear, you find yourself wanting to hold out a sheet for safety beneath her in case she falls; Cruz makes even her most egregious actions something the audience can empathize with. Like Ana, you can’t help but find yourself adoring her.

To hold one’s own opposite such a powerful actress as Cruz requires a very special young performer, and in Milena Smit, Almodóvar found her. Thin and pale while Cruz is curvy and dark, the physical dissimilarities between the two actresses further highlight the differences between their two characters. But Smit is so much more than just a striking screen presence; she’s able to convey both youthful naivete and the cynicism that comes with having experienced trauma. She and Cruz have a warm, genuine chemistry that carries over offscreen; during the post-screening press conference at the New York Film Festival, Cruz held Smit’s hand and supported her with smiles, much as a mother would a daughter. The two of them together are the heart of the film.

Conclusion

During the press conference, Almodóvar described the victims of the dictatorship as “condemned by Franco to a kind of nonexistence.” It’s hard to think of a more beautiful cinematic tribute to the importance of keeping their memories alive than Parallel Mothers. The final scenes, in which Janis brings Arturo to her home village to begin the excavation, are a powerful reminder that no victim of persecution ever deserves to be forgotten. And in using the medium of melodrama to convey such a message, Almodóvar has given us one of his best films in years.

What do you think? Are you a fan of Almodóvar? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Parallel Mothers screened as the closing night film at the 2021 New York Film Festival. It opens in the U.S. on December 24, 2021, and in the UK on January 28, 2022. You can find more international release dates here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.