Dads, Single Moms & Transport: The Obsessions Of Cameron Crowe

Eric D. Bernasek lives on the island just north of…

Kubrick was fond of symmetry. Wes Anderson loves The Kinks. The name JJ Abrams is synonymous with lens flare. Tarantino has a foot fetish. Directors often have obsessions, whether visual, thematic, or otherwise. Aside from his decades-long devotion to a very particular kind of romantic comedy – romance plus personal crisis, comedy for good measure – Cameron Crowe has amassed a sizable list of creative fixations. Some are obvious, from first-rate music cues to precocious moppets. Others, less so.

Because Crowe’s movies are so strongly character-driven, it’s only natural that relationships and families, fathers and mothers in particular, play outsized roles in his scripts. But Crowe’s parental fixations are more specific. Many of his movies feature single mothers. Almost as many feature protagonists haunted by fathers who hardly ever appear onscreen and yet loom large over the lives of their children.

In addition to mom and dad, Crowe loves cars, in particular, as well as buses and planes and all sorts of things that move. His characters spend surprising amounts of time shuttling themselves or being shuttled from one place to another and laying down dialogue while doing so. Aaron Sorkin has his walk-and-talk. Crowe has this. Moreover, major plot points in Crowe’s movies frequently occur while his characters are in or around modes of transport.

In this article we’ll take a look at the eight narrative, fiction films written and directed by Cameron Crowe to point out when and to discuss why he returns so frequently to dads, single moms, and transport.

(Spoilers will follow. It’s unavoidable.)

Say Anything (1989)

Cameron Crowe’s career in film started with the screenplay for Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), which was based on Cameron Crowe’s book by the same name and directed by Amy Heckerling. Generally dismissed at the time of its release, fondness for Fast Times has lingered in the years since. Crowe’s second screenplay, The Wild Life (1984), didn’t fare as well. The movie is now all but forgotten, despite its boasting an enticing cast of Eighties also-rans. Say Anything, the first movie that Crowe wrote and directed, has been much more successful.

Of his eight films, it wouldn’t be too controversial to say that Say Anything is the Cameron Crowe movie most universally beloved. It would take some time for Crowe to grow into being a fully competent director, but in many ways he managed to get things right the first time.

In the list of Crowe’s cinematic dads, James Court (John Mahoney) is the most conspicuous. At first, the relationship between James Court and his daughter Diane (Ione Skye) is endearing, but over the course of the movie it spoils. Diane’s hero-worship of her doting father is eventually crippled by his deceit, however well-meaning it might be. As the truth about Mr. Court’s criminality becomes more clear, his affection for his daughter starts to appear unhealthy if not altogether unwholesome, an implication that adds depth to the virtual love triangle between Diane’s father, Diane, and Diane’s boyfriend, Lloyd.

Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack) lives with his sister Constance (Joan Cusack), first in the line of Crowe’s single mothers, and her son Jason (Glenn Walker Harris Jr.), first in the line of Crowe’s precocious moppets. Lloyd carries a white-hot torch for Diane Court. But he also carries a torch for his Chevy Malibu, which is practically another character in the script. A significant portion of the movie’s screen time takes place in or near Lloyd’s car, including some of the most consequential scenes.

Of course there’s that scene, the one in which our young lovers “park” Lloyd’s car at the beach while Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” plays (crucially) in the background. Notably, this is one of the few clearly audible lines: “When I want to run away, I drive off in my car.” Of course, Gabriel’s ballad will return for that other scene, the one destined to forever be an iconic depiction of teen romance on film. When he holds his boombox aloft, the voice of Peter Gabriel broadcasting Lloyd’s undying love into Diane’s bedroom window, Lloyd is leaning against the hood of the Malibu.

“I don’t even feel that way about my car, man.”

The Malibu is also there for Diane and Lloyd’s first night out together, at a graduation party. Lloyd’s unasked for duties as keymaster, combatting the evils of drunk driving, end up obligating him to drive home a stranded partygoer. Having spent so little of the evening physically together – though so much of it watching one another from afar – Diane and Lloyd are eager to be alone, but that desire is frustrated by their unwelcome passenger.

This scene is shot from the dashboard of the Malibu, with Lloyd driving and Diane sitting on the passenger side of the car’s front, bench seat. Their unwanted guest sits in the back, leaning over the seat in front of him, visually separating Lloyd and Diane. Once they’ve finally dropped him off, the camera leaves its spot on the dash, briefly showing the couple together in the same frame, from the vantage point of the driver’s side window, before retreating to a chaste shot reverse shot set-up that once again physically separates the increasingly lovelorn protagonists.

Shortly, we’ll see them in the same frame, but outside of the car. We don’t see them together in a car – Mr. Court’s car – until several scenes later, when Lloyd is teaching Diane how to drive manual transmission. By teaching Diane to drive, Lloyd is enabling her to become more self-reliant, more independent. He is also, in a very real sense, stepping into Mr. Court’s territory, potentially separating father and daughter. During this scene Mr. Court in fact looks on disapprovingly, and unseen, from a nearby window. Significantly, the scene ends with Diane and Lloyd’s first kiss, just before the two switch places, climbing over one another, and drive off into the implied sunset of a romantic montage that ends with the aforementioned scene at the beach.

Later, when Diane reluctantly breaks up with Lloyd at the insistence of Mr. Court, she does it in the Malibu. At the start of the scene, both Diane and Llloyd are in the same frame, with the camera on the passenger side of the car so that Diane appears closer to the viewer. As Lloyd ramps up to making a momentous declaration, the camera shifts to his side of the car, but when Diane realizes what he’s about to say and tries to stop him, it shifts back. Lloyd finally says, for the first time, “I love you,” and the camera once again shifts briefly back to him.

Diane is uncomfortable. This is too much for her. As she continues speaking: “Lloyd, let’s not start putting things on this level.” Lloyd: “What? This is a good level.” We see a shot of the Malibu driving down the street, from the right- to the left-hand side of the frame (i.e., not “forward”). When we see the interior of the car again, the camera is on the hood, looking in, with Diane and Lloyd side by side. But it only stays there briefly before returning to the shot reverse shot setup from the start of the scene.

By the time their conversation has finally progressed to the actual break-up, Lloyd has pulled over and stopped the car, and the camera continues to shift places, from Diane’s side of the car to Lloyd’s, apparently in unison with the various shifts in power that happen in the course of their conversation.

It only gradually becomes clear to Lloyd what’s happened. At one point he comes to the conclusion that Diane has ended things with him because of Mr. Court. This accusation escalates their exchange from a painful conversation to an argument, and it continues like this until Diane remembers something her father had given to her earlier.

“I gave her my heart. She gave me a pen.”

Mr. Court suggested that Diane give Lloyd something as a parting gift, a sort of pathetic consolation prize. And though at the time Diane is repulsed by the idea, now she digs through her purse for the pen her father had suggested and, half-possessed, offers it to Lloyd.

At this point the camera is on Diane’s side of the car. When she reaches for the pen she turns toward the audience and away from Lloyd. In the moment that she turns back around to give him the pen, almost brandishing it in his face, Lloyd looks at it with disgust, maybe even horror. He won’t take it, so Diane puts the pen down on the dashboard. Then the camera returns to the hood of the car, looking in, so that the pen sits on the dash, a tiny but significant barrier in between them.

Lloyd’s Chevy Malibu is his sanctuary. In the scenes following their break-up, we’ll see Lloyd driving aimlessly in the rain, taking shelter in the one place that belongs to him. Diane too leaves the break-up and goes directly to her own car, where she sits down in the driver’s seat, closes the door, and cries in the privacy of that personal space. For the couple, the Malibu was a place of intimacy, not just in a general but also a very specific, very literal, sense. That their break-up happens in the car taints that memory.

At the same time, the pen is a much more specific violation of Lloyd’s space. It’s a symbol of Mr. Court, by which he physically intrudes into their relationship and separates them from each other. That the symbol, a pen, is also explicitly phallic adds a layer of perversion to the intrusion and suggests, again, that the three main characters in Say Anything find themselves in a rather unconventional love triangle.

“You just described every great success story.”

Happily, the break-up doesn’t last, and at the end of the movie Mr. Court is in prison, whereas Diane and Lloyd are leaving together for Diane’s fellowship in England. The final scene of the film finds them sitting side by side on a plane. It’s Diane’s first flight, and she’s scared. To reassure her, Lloyd says, “If anything happens, it usually happens in the first five minutes of the flight, right? So when you hear that ‘smoking’ sign go ding, you know everything’s gonna be okay.”

Over the next few minutes we’ll see them awkwardly waiting for that ding. Diane says, sounding worried, “Nobody thought we’d do this. Nobody really thinks it will work, do they?” Lloyd’s reply is pure Cameron Crowe: “No. You just described every great success story.” In the very last shot of the movie we’re looking down on the two of them, a slight high-angle that indicates they’re looking up at the “no smoking” sign, anxiously. After several tense moments we finally hear the ding, and the screen cuts to black.

The airplane is a way of depicting the giant leap of faith that Diane and Lloyd are taking together. And Lloyd’s comment about the “ding” is a perfect metaphor for their relationship so far. They’ve already weathered the turbulence of the figurative “first five minutes” of what they hope will be their lives together, and now that that’s behind them, “everything’s gonna be okay.”

Singles (1992)

As you might expect, a movie titled Singles doesn’t have much to say about fathers or single mothers or parents in general. That said, the two main characters, Linda (Kyra Sedgwick) and Steve (Campbell Scott), do have a brief brush with parenthood when Linda unexpectedly becomes pregnant. But her pregnancy (and their relationship) is ended by a very Cameron Crowe appropriate deus ex machina, a car crash.

Aside from that one very consequential automotive event, the characters in Singles don’t spend nearly as much time in their cars as do Lloyd Dobler and Diane Court. Still, Steve’s career as a city planner is defined by the ultimate failure of his proposal for a “supertrain,” which Crowe ham-handedly fashions into a metaphor for the movie’s main theme – the aspiration of singles to become couples. As Steve proclaims, “If we can get the single car driver on the supertrain, we can change the city!” And as the mayor (a cold-hearted Tom Skerritt) responds, with finality, “I’ve been burned by this train situation before. People love their cars.”

There’s also a boat to Alaska, a rather destructive car stereo installation, and a strained romantic callback in an elevator. Another transport-related theme worth mentioning involves garage door openers, which may be the clumsiest symbol of intimacy ever foisted on viewers.

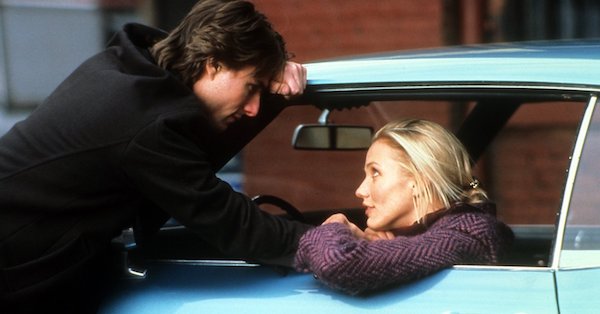

Jerry Maguire (1996)

Crowe’s first mainstream success, Jerry Maguire, involves a sports agent, Jerry Maguire (Tom Cruise), who has a crisis of conscience over the rampant greed in his business and is inspired to write a manifesto with a very simple message: “fewer clients, less money.” That change of heart costs him his job at a major agency, so he strikes out on his own in pursuit of a more ethical business model. He’s joined by Dorothy Boyd (Renée Zellweger), a co-worker whose dedication to Jerry’s cause is part idealism, part infatuation. Together they shoot for success with Arizona Cardinals wide receiver Rod Tidwell (Cuba Gooding Jr.), the only client Jerry has left.

Many of the themes typical to Cameron Crowe are at play in Jerry Maguire. Most prominent is Dorothy Boyd, who is an outright paean to single mothers and thus a compelling tribute to hard work, self-sacrifice, and, well… romantic desperation. Not only is she the mother of Ray (Jonathan Lipnicki), one of Crowe’s most memorable moppets (“The human head weighs eight pounds!”), she’s also flanked by her loyal, pragmatic, and single sister, Laurel (Bonnie Hunt) as well as a veritable Greek chorus of divorcées who congregate regularly in her living room to debate the relative merits of men.

The movie’s reverence for single mothers is cemented at one point by Rod, who opines, “The single mother, that’s a sacred thing.” And though Dorothy may at first be surrounded by a cloud of desperation, as the movie progresses she is increasingly treated with the sort of veneration Rod describes.

“Suddenly, I was my father’s son again.”

Although a father is missing from Dorothy’s family equation, the idea of fatherhood is repeatedly brought up in the film. As much as this is a story about a woman who wants a man (and a man who wants to be a success), it’s also about a boy who wants a father. Dorothy’s son Ray is not the only one who feels that way. During a candid chat between Ray and Jerry (who at the time is very drunk), Ray wants to talk about a trip to the zoo he once shared with his deceased dad, while Jerry wants to talk about his own father.

We never see or hear from Jerry’s dad, but there is a father figure in Dicky Fox (Jared Jussim), whom Jerry calls his “mentor” and who pops up a few times (in apparent flashbacks, removed from the story proper) to deliver pithy observations about life. Perhaps most significantly, Jerry characterizes the moral epiphany that animates his entire story by saying that “Suddenly, I was my father’s son again.” It indicates a very specific return to grace (and it’s a sentiment that will be echoed loudly in Elizabethtown).

In addition to all these parental ruminations, Jerry Maguire certainly has its share of transportation. As the devoted agent to a member of the NFL, Jerry’s life involves a lot of traveling and a lot of airports. Here Crowe treats airports as places not just for arrivals and departures, but also as places where people go off in different directions from one another.

“First Class is what’s wrong, honey. It used to be a better meal. Now it’s a better life.”

Jerry and Dorothy first meet at an airport, coming back from the junket where Jerry was inspired to compose his manifesto. On the plane, just moments before they meet, we see Dorothy eavesdropping on Jerry, apparently daydreaming about what it might be like to be with him (or someone like him). And later, on the way to the airport in Dorothy’s car, Jerry first starts to fall for (not Dorothy but) her kid.

Jerry and Dorothy share a few more pivotal moments while in transit or while standing anticipatorily next to modes of transportation. It’s on an elevator, after just having walked out on their jobs, that the future couple witnesses an exchange that will be the movie’s big romantic callback. And later, while standing next to a moving van, Jerry will stave off his own desperation by half-hypothetically proposing to Dorothy.

Another transport-related scene, though not particularly consequential to the plot, is quintessential Cameron Crowe. Shortly after landing a client that he (wrongly) thinks will steady his precarious business, Jerry is driving alone in a rental car, scanning the radio, when he lands on the Tom Petty song “Free Fallin’.” He immediately sings along, full-throated and oblivious to the irony. This is a trope that Crowe first used in Say Anything and that would reach its zenith in his next movie.

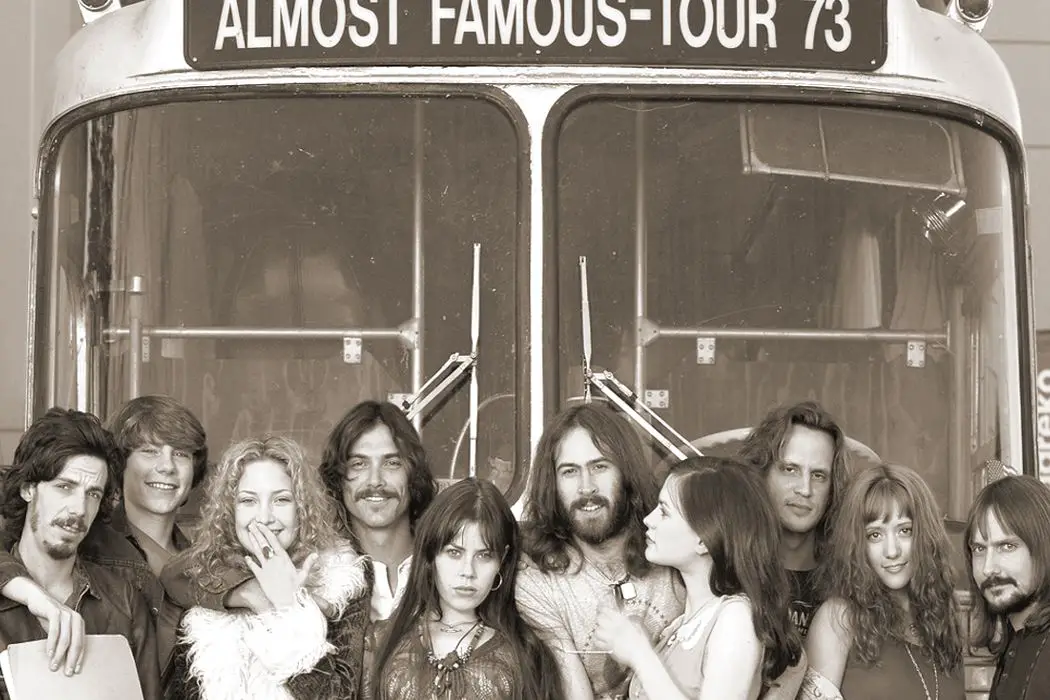

Almost Famous (2000)

If the eight movies on this list were the eight tracks on Led Zeppelin’s legendary untitled fourth album, Almost Famous would appropriately be Cameron Crowe’s “Stairway to Heaven.” It tells the semi-autobiographical story of his life as a prodigy of rock criticism, before he turned to screenwriting. It is therefore Crowe’s most personal film. In many ways, it’s also his best.

Aside from the depiction of Crowe’s real-life mentor and the progenitor of modern rock criticism, Lester Bangs (Philip Seymour Hoffman), there are no real father figures here. Lester does have a few important scenes during which he imparts wisdom upon his young protégé, William Miller (Patrick Fugit), who is the fictional version of young Cameron Crowe.

But the parental landscape is dominated by William’s mother Elaine (Frances McDormand), who is also loosely based on Cameron Crowe’s own mother, Alice Marie Crowe. Fun fact: Alice is the Stan Lee of Cameron Crowe’s cinematic universe, having made cameo appearances in every one of his movies except Aloha, the most recent. Elaine Miller is a single mother without peer, and with no need of a companion. She is also a towering presence in the lives of her son, William, and daughter Anita (Zooey Deschanel).

Elaine Miller and Dorothy Boyd are both single mothers, but they’re fashioned from different archetypes; in fact, Elaine is altogether in her own category. She’s a homeowner and a college professor. Her specific area of academic interest is unspecified, but at one point we see her lecturing a class on Carl Jung and the collective unconscious. Her conversations with William involve To Kill a Mockingbird and Livia Drusilla, the mother of Tiberius, the Roman Emperor. So… Psychology? Philosophy? Literature? History? Regardless, her efforts are devoted, first and foremost, to raising her children.

With William, those efforts are going well. But with Anita, Elaine’s success appears tenuous. She personally characterizes their relationship by saying that Anita is “rebellious and ungrateful of [her] love.” For her part, Anita complains, “First it was butter. Then it was sugar and white flour. Bacon, eggs, baloney, rock and roll, motorcycles. Then it was celebrating Christmas on a day in September when you knew it wouldn’t be commercialized! What else are you gonna ban?” Elaine’s response: “I’m trying to give you the CliffsNotes on how to live life in this world.” She sees her role as a mother in very specific but very unconventional terms.

“Rock stars have kidnapped my son!”

Beyond securing the safety and ultimate well-being of her children, Elaine Miller is not portrayed as having needs or personal desires or, for that matter, a social life, all of which distinguish her from Dorothy Boyd. Neither are we told anything about Elaine’s past or about William and Anita’s father, who is made conspicuous by his complete absence from their story.

One of the only clues we get about Elaine is a framed copy of the “Serenity Prayer”: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference”, which hangs on a wall in her modestly decorated house. The prayer’s frequent association with Alcoholics Anonymous suggests that Elaine may be more complicated than the script otherwise suggests.

Substance abuse, and its avoidance more specifically, is a theme that repeatedly comes up with Elaine. When William and Stillwater arrive at their hotel in Tempe, Arizona the desk clerk delivers a very simple message from Elaine – “DON’T TAKE DRUGS!” – itself a callback to an earlier scene in which she yells the same words at William as he walks away from her, on the way to his very first rock concert.

Later, when Elaine ends up on the phone with Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup), she admonishes him by saying, “This is not some apron-wearing mother you’re speaking to. I know all about your Valhalla of decadence, and I shouldn’t have let him go. He’s not ready for your world of compromised values and diminished brain cells that you throw away like confetti.”

Whatever the truth about her past and its influence on her present behavior toward her children, Elaine Miller is a fully dedicated and fiercely loving, if not traditionally affectionate, single mother. Following their phone call Russell, rattled, tells William, “Your mom kinda freaked me out.” William reassures him, “She means well.” She clearly does.

Though there’s a lot more that could be said about Elaine Miller, there’s even more to say about the cars, buses, and planes that fill this movie. Because Almost Famous is about a rock band on tour, it’s part road movie. So there are quite a few scenes that involve transport, in one form or another.

It’s while in the car that William first learns his mother has been lying to him about how old he is; he’s two years, rather than one year, younger than his classmates. In the next scene William and his mother stand curbside as Anita and her boyfriend pack up his car so that she can leave home and become a stewardess. Meanwhile, the Simon & Garfunkel song “America” plays in the background; it’s about traveling the country by bus. Shortly, William’s mother will drive him to his first writing assignment, at the San Diego Sports Arena: “I’ll give you 35 bucks. Give me a thousand words on Black Sabbath,” where he first crosses paths with the fictional band Stillwater, as they get off their bus, affectionately dubbed “Doris.”

“Doris is the soul of this band.”

As Stillwater’s singer, Jeff Bebe (Jason Lee) proclaims, “Doris is the soul of this band.” A considerable portion of the movie takes place on board Doris, including a handful of consequential scenes. The one most worth mentioning takes place just after the band has had a fight over their first t-shirt (and its subtext), and guitarist Russell walks out on his bandmates for a night of decompression and psychedelic drugs.

When he gets back on the bus the next morning, everyone is feeling hurt and no one is interested in talking about it. Through the magic of Elton John and group sing-alongs, the bus full of band members, crew, and groupies come together again and all is forgotten. It’s the most extreme possible expression of Crowe’s driving-and-singing trope, this time with a full chorus instead of just a solo.

As in so many other instances, Doris the Bus is a place of intimacy, where the characters share things with one another in a special zone that’s sheltered from the outside world. It’s during the “Tiny Dancer” sing-along that Penny Lane (Kate Hudson) anoints William as, not “the enemy,” as the band has half-jokingly been referring to him, but as a full-fledged member of the Stillwater Family (and, by extension, the traveling circus of outsiders and misfits that populate the wider world of rock to which Stillwater belongs). Anxious that his trip, meant to last a few days, has stretched into weeks, with no end in sight, William worries aloud, “I have to go home.” Penny’s obvious but still affecting reply: “You are home.”

Later in their tour, Stillwater’s label will insist that the band forgo Doris and travel by private plane instead, hoping to make more money by playing more shows. Their decision to go along with the label’s plan is emblematic of a common theme not just in rock and roll but in the universe of Cameron Crowe: staying authentic vs. selling out. On their very first flight the band will have a brush with death that provokes a series of escalatingly antagonistic confessions from the band and an impassioned monologue from William.

As with Doris the Bus and Lloyd Dobler’s Malibu (and several other examples), this scene on the plane shows how Crowe treats modes of transport as places of intimacy where his characters feel and express themselves more freely and also as useful devices in moving a story forward. The end of this particular scene is exemplary of another one of Crowe’s well-worn tropes: diffusing the intensity of an emotional moment with a joke.

Aside from cars and buses and planes, airports too figure heavily in Almost Famous. Much like in Jerry Maguire, airports here are primarily places where Crowe’s characters separate from one another or reunite. Once they’ve landed safely, William and the band walk, silent and shell-shocked, through the terminal for a moment before going their separate ways – Stillwater, on to the rest of their tour, William, finally to the offices of Rolling Stone to submit his cover story on the band. The near-crash and the mid-air confessional have facilitated a catharsis, and Russell finally tells William what he needs to hear: “Write what you want.”

“My cherie amour, distant as the Milky Way…”

In a sequence just before this one, William is at another airport, saying goodbye to Penny Lane. He runs through the terminal, alongside her plane, as it taxis away from the gate and toward the runway. When he reaches the end of the terminal, he crashes up against the window and watches as she disappears from sight. Penny is, as she always was and likely will forever be, just out of his reach.

Several scenes later William finds himself in yet another airport, this time on his way back home, finally. By chance he reunites with his sister, Anita, who is now a stewardess just getting off of work. It’s worth mentioning that Crowe connects Penny to Anita in a recurring bit in which Penny pretends to be a stewardess herself.

There are a few meanings here. As a “band-aid,” Penny sees herself as a sort of literal stewardess, responsible for shepherding aspiring musicians into superstardom; regarding Russell, she says, “He’s my last project. I only do this for a very few people… All the guys are good, but he could be great.” The connection is also obviously meant to remind us of Anita, who is a stewardess and whose final act of sisterly affection before leaving home was to bestow a short stack of contraband LPs upon her brother, thus inspiring the musical and professional quest that’s led him to Penny. Finally, connecting Penny and Anita is a way of confirming that, despite how William feels about her, Penny is destined to be not a love interest but more of a sibling.

Finally, it’s oddly appropriate that the Cameron Crowe movie with some of his most memorable characters ends in a musical montage featuring almost as many images of transport as people. In fact, it starts with a shot of Doris, driving toward the camera – the marquee reads, “NO MORE AIRPLANES – TOUR 74” – and ends with another shot of Doris, driving into the sunset. The Led Zeppelin song “Tangerine” plays, wistfully: “Tangerine, tangerine. Living reflections from a dream. I was her love. She was my queen. And now a thousand years between.” Certainly, in context, the “she” refers to Penny. But the juxtaposition of song and image suggests that it could refer just as appropriately to Doris and to the road.

Vanilla Sky (2001)

Out of the eight movies on our list, all but two of them were written entirely by Cameron Crowe. You could say that Crowe is a writer-director in the same way that some musicians are singer-songwriters; he writes and “performs” his own material. As a remake of Alejandro Amebábar’s Abre los Ojos (“Open Your Eyes”), Vanilla Sky is the cover on Crowe’s eight-song album of otherwise original material.

Yes, We Bought A Zoo (2011) is also based on someone else’s work. We’ll get to that. But that movie is still very much a Cameron Crowe joint, whereas this… This is something else entirely. The love story is still there, but the comedy is gone. In its place is a psychological thriller that’s been grafted onto a sci-fi story about cryonization and the nature of reality.

“Without the bitter, the sweet isn’t sweet.”

On the one hand, Vanilla Sky is the work of a director whose last effort won a bunch of awards and can now afford to close down Times Square in order to shoot the opening scene of his new movie, in which Tom Cruise drives a Ferrari through the completely deserted streets of New York City. On the other hand, Vanilla Sky is also the work of a director who wants to prove he can do something different. It’s the cinematic manifestation of William Miller’s (little Cameron Crowe’s) ineffectual rant in Almost Famous: “Sweet? Where do you get off? Where do you get sweet? I am dark and mysterious and pissed off!”

Aside from all the posturing, many of Crowe’s hallmarks are still in tow. There are no single mothers this time around, but daddy’s definitely here. Cruise plays David Ames, a rich playboy living off the professional life and fortune bequeathed to him by dear old dad, who quite literally looms over his son in the form of a giant, grinning portrait of his face that fills an entire wall of David’s swanky apartment. And then there’s the court-appointed therapist, McCabe (Kurt Russell), who we are explicitly told is David’s idealized image of a father, based on Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird, and who ends up being kind of a ghost.

“It’s very important to have the right car to take you wherever you want to go, 24 hours a day.”

As for transport, there’s that opening scene with the Ferrari. (It’s worth noting that more than half of Cameron Crowe’s movies start with or in some form of transportation.) There’s also another pivotal car crash. Julie Gianni (Cameron Diaz) is one of David’s many lovers, and her jealous obsession with him literally drives the two of them off an overpass, causing the accident that kills her and disfigures him, setting the rest of the plot in motion.

In addition to these physical manifestations, Crowe’s auto-fixation also plays out in metaphor. He compares the human body to a car at one point in dialogue: “It’s very important to have the right car to take you wherever you want to go, 24 hours a day.” He also does this visually, by cross-cutting a quick shot of the car wreck into a later scene in which David downs a bottle of pills and his body comes crashing to the floor.

And, once again, there’s another consequential scene in an elevator, this time allowing for a minute or two of explicatory dialogue as we ascend to the film’s climax on a rooftop above New York. As usual, Crowe is using modes of transport as devices that literally move the story forward.

Elizabethtown (2005)

After the failed attempt at remaking himself with Vanilla Sky, Cameron Crowe returned to familiar territory as writer/director of Elizabethtown, which like Jerry Maguire is about a man, failing and flailing, who might as well fall in love as he gets his life back on track. Speaking of tracks, this movie starts with a truck backing up, moves on to a helicopter, then a golf cart (indoors, so… inexplicably), reconvenes on an exercise bike, takes a shuttle to an airplane, then a rental car, then the same rental car with another care, and then the rental car one last (looong) time, with a few elevator rides thrown in for good measure. If Crowe was going to reclaim his role as a purveyor of emotionally wrought romantic comedies, he might as well bring back the old way of doing things, in toto.

We’ll get back to all that transport, but let’s not forget our parental figures. There are no single moms here, but dad is hanging around, heavily, like a benevolent ghost. Drew Baylor (played exasperatingly by Orlando Bloom) has somehow lost his employer a rather big sum of money – “It’s big. So big you could round it off to a billion dollars.” – by designing a shoe so bad that it “may actually cause an entire generation to return to bare feet.” In precisely what way it may do so, we are never specifically told, but the details are ultimately unimportant in the face of the generalities of a failure so colossal that it drives our pathetic hero to contemplate suicide by exercise-bike-assisted stabbing.

“We are intrepid. We carry on.”

In his prolonged moment of despair Drew receives a call from his sister to let him know that his dad has died and can he please immediately get on a plane to Kentucky where arrangements need to be made for the funeral. It’s while on the plane that Drew meets Claire (Kirsten Dunst), who takes a non-professional interest in her passenger and his imploding life.

Like the father of David Ames in Vanilla Sky (and, less explicitly, the father of Jerry Maguire) Drew’s father, Mitch Baylor (Tim Devitt), towers over this movie even though he barely ever appears on screen. There is a (corny? creepy?) scene in which we see Mitch in his casket. But there’s a much more significant montage of Drew’s memories of the Baylor patriarch, appearing in shadow and/or out of focus and/or partially obscured: little Drew clomping around in his dad’s shoes (too big to fill), having his seatbelt buckled paternally, and cheerfully dancing around an empty office while Mitch hoists a cardboard box of personal effects over his head (a reference to dad’s own past brush with failure).

“We should’ve taken this trip years ago.”

In the latter part of the film, Mitch Baylor appears exclusively as an urn of cremated remains, which Drew brings with him wherever he goes, including the car, where Mitch the Urn rides shotgun after being affectionately buckled in by his son. The film culminates in a road trip Drew and his cremated dad take together, something they’d been planning to do but Drew’s professional ambitions had prevented. This sequence is peak Cameron Crowe, and it’s not just the car ride that makes it so.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the “Tiny Dancer” bus chorus in Almost Famous was the most extreme possible combination of Crowe’s love for pop music and transportation, but he outdoes himself in Elizabethtown by marrying the road movie to the mixtape. Drew’s cross-country drive with dad is fully orchestrated by a “map” consisting principally of “42 hours and 11 minutes” worth of mix CDs (and accompanying driving directions) prepared by Claire.

In that way Claire explicitly lives up to her role as “stewardess” to Drew. “How could I leave you in distress?” she says to him at one point, not just reinforcing her status as a manic pixie dream girl – a phrase her character in fact inspired – but also confirming that Drew is the damsel in need of saving.

A few final notes: Samson, the grade-school-aged son of Drew’s cousin Jessie (Paul Schneider) and a Dennis-the-Menace-style anti-moppet, tries to take his dad’s car for a spin, which leads to a confrontation over fatherly responsibility between Jessie and his own dad. The love story that brought Drew’s dad and mom together begins in an elevator. And lastly, this movie is, in part, about shoes, which are (marginally) another mode of transport.

We Bought A Zoo (2011)

In addition to Vanilla Sky, We Bought a Zoo is the only other movie Cameron Crowe directed for which he did not write an original screenplay. In this case, Crowe’s script was based on a book, the true-life story of one Benjamin Mee. He was also helped by screenwriter Aline Brosh McKenna, who was responsible for writing the scripts to 27 Dresses, The Devil Wears Prada, and others. It’s hard not to wonder if the relative failures of Vanilla Sky and (especially) Elizabethtown convinced Crowe’s producers that he needed a prefab, feel-good story and a steadier hand on the wheel beside his own.

Fortunately for them, We Bought a Zoo was a success. But at what cost? This is, by far, the safest and most generically “Hollywood” of Crowe’s movies. It’s therefore the most emotionally manipulative. Starring Matt Damon as Benjamin Mee, an attractive widower whose foundering career as a writer and fraught role as a single-father has him searching for new digs where he and his two kids can start over. What he finds is something Lloyd Dobler called a “dare to be great situation” – a lovely old house in the country with an attached animal park in need of a brave caretaker.

His daughter Rosie (Maggie Elizabeth Jones, the precocious moppet to end all precocious moppets) is totally on board. His son Dylan (Colin Ford)… not as much. Not to worry. The zoo comes equipped with not only a sizable cast of photogenic animals. It has quite a few photogenic humans as well. Fortunately for Dylan, there’s Lily (Elle Fanning) to help him (eventually, predictably) give up the mopey teenager bit and forget the friends he left behind. Benjamin, meanwhile, can turn to Head Zookeeper Kelly Foster (Scarlett Johansson) to learn the ropes and (eventually, predictably) move on from the staggering loss of his wife’s death from cancer.

In short, this is a predictable movie that plays, predictably, on your emotions while giving you beautiful people (and animals!) to look at. This isn’t a big departure from Cameron Crowe’s previous efforts – Jerry Maguire too is all of that, more or less – but at the same time it doesn’t feel authentic either. Nevertheless, many of Crowe’s trademarks are still accounted for.

“Their happy’s too loud.”

On the most basic level, this is a story about being a good father, in this case a single father (as opposed to a single mother). Fatherhood is certainly an ongoing obsession for Crowe, but he usually approaches it from the vantage point of the son rather than the father himself. Despite that promising twist, nothing really unique or genuinely profound comes from the opportunity.

Crowe’s enthusiasm for transport is similarly handicapped, in this case because so much of the story takes place in a single location, leaving little opportunity for car rides and the like. In Elizabethtown, Drew took a golf cart down a hallway indoors to a meeting with his boss. In We Bought a Zoo, with nearly twenty acres of animal park to maintain, there isn’t a golf cart in sight. Still, there’s that 9.2 mile drive to the nearest Target. And Dylan has to be shuttled to and from school. Nonetheless, the amount of screen time devoted to Crowe’s typical drive-and-talk is here drastically reduced.

“I like the animals, but I love the humans.”

Despite that, there’s one early scene that delivers: Benjamin and Rosie go looking for a new house with their realtor, Mr. Stevens (the delightful JB Smoove). You can easily imagine another director taking them from house to house to see a disappointing series of exploding faucets and horridly wallpapered rooms, but Crowe does something else. Instead, the trio drive from house to house, peering out at their prospects from the comfort of the car, never getting out.

It’s not a small detail, something you could pick out to fit a familiar pattern. For Cameron Crowe, a car – or a plane, or a bus, or whatever – is a place of closeness. In this case, the search becomes instantly more personal when Rosie reveals nonchalantly to Mr. Stevens that “our mommy died.” Someone who had moments before been “a stranger,” as Benjamin reminds his daughter, enters into the familiarity of the Mee Family. That change is facilitated by the closeness and intimacy of the car, where the three characters are protectively isolated from the world of actual strangers outside.

Aloha (2015)

True to form, Aloha starts on an airplane. Actually, it starts with a brief montage and a nostalgic voiceover, à la Jerry Maguire. But the story proper starts on a plane. Also like Mr. Maguire, Aloha’s protagonist, Brian Gilcrest (Bradley Cooper), is a broken man (this time physically as well as professionally and emotionally) hoping to put his life back together after a series of setbacks.

Having left the military for the public sector, Gilcrest is now employed by billionaire Carson Welch (Bill Murray), who is hoping to put a satellite in orbit and needs Brian’s help in negotiating with the locals in Hawaii. Brian has history on the islands, and his return there will bring him back in touch with Tracy (Rachel McAdams), an old flame now married to a man of few words but many glances, John “Woody” Woodside (John Krasinski).

Carson Welch, and thus Brian too, will need the help of the military to launch a rocket and get his satellite in orbit. That means, naturally, that Brian is assigned an Air Force escort/“watchdog”/monitor/sidekick/love-interest in Allison Ng (pronounced “ing”). The “one-quarter Hawaiian” Ng is played, perplexingly, by fair-skinned redhead Emma Stone. More perplexing still is the plot, which is an unsatisfying blend of over-complicated and under-engaging.

It’s all too tempting to blame the story’s failures on the presence of Ng, who is more than anything else a distraction from Brian’s relationship with Tracy and, much more consequentially, Tracy’s daughter Grace (Danielle Rose Russell). As we learn, helpfully, from Tracy: “Grace is twelve,” and “Brian and I haven’t seen each other in… what? Thirteen years.” The most effective, and most genuinely touching, scenes in the movie involve Brian and Grace and Tracy. The most irritating (and, frankly, slapdash) scenes involve Brian and Allison Ng.

“Second chance. Who doesn’t want a second chance?”

Is it possible that there was once a version of this screenplay without Ng? It’s conceivable that a more effective (and more serious) version of the film might go something like this: Brian returns to Hawaii; he and Tracy confront their past together and their lingering feelings for each other; feeling threatened and/or unappreciated Woody leaves his little family but later returns to be warmly welcomed home by them; acknowledging that Woody and Tracy belong together Brian leaves again, restored in spirit after having bonded with his daughter; and all of it without getting sidetracked by the obligatory like/love story Brian shares with Ng. Like that other letter Diane Court writes to her father but never gives to him, it’s nice to think a simpler and more effective version of Aloha might have once existed.

But we’re getting sidetracked… What of dads and single moms, and transport? The only mom here is Tracy. Though she’s not a single mom, her husband Woody is frequently absent, both physically and emotionally. And the paternal status of the two dads – Woody and Brian – is an element of the story, but one that’s not (or is not allowed to be) centrally important.

Meanwhile, there are planes and cars and all the rest. But in this case the most significant mode of transport is the rocket and the satellite launch that make up the movie’s goofy climax. We’ve already spent too many words on Aloha to describe this convoluted (and confounding) bit of the plot in detail. Suffice it to say that the satellite – which becomes a symbol of both the evils of the military industrial complex and the regrettable triumph of profit over humanity – is spectacularly destroyed by pop culture. There may be no cinematic climax more emblematic of Cameron Crowe.

The Concerns of Cameron Crowe

Over eight films and nearly thirty years Cameron Crowe has returned, over and over again, to similar tropes and themes. Many of his movies have featured strong father figures and even stronger single mothers. All of his movies have used cars and buses and planes and other forms of transportation in now familiar ways – as symbols of freedom, as places of intimacy, as plot devices that move the story forward. Examining this tendency can help to understand his work, by making connections that run throughout his oeuvre.

These are only a few of Cameron Crowe’s cinematic fixations. Can you see some others? What other director-specific obsessions have you noticed?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Eric D. Bernasek lives on the island just north of the island that is Montreal. He thinks too much and writes too little. He is currently working on a book about movies from your childhood: "Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?" – Authority and Rebellion in Movies About High School.