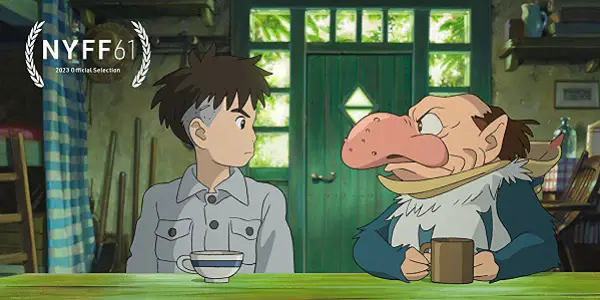

New York Film Festival 2023: THE BOY AND THE HERON

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

“There’s nothing more pathetic than telling the world you’ll retire because of your age, then making another comeback.” So said animation legend Hayao Miyazaki in his original project proposal for The Boy and the Heron back in 2016—just three years after he had announced he was retiring from the production of feature films following the release of The Wind Rises. Miyazaki continued: “Doesn’t an elderly person deluding themself that they’re still capable, despite their geriatric forgetfulness, prove that they’re past their best? You bet it does.”

Miyazaki is undeniably a genius, so I’m loath to correct him in any way, but this is one instance in which he is absolutely wrong. Seven years after he first began work on The Boy and the Heron—needless to say, he didn’t wait for the official go-ahead on his proposal before he started storyboarding—the film is finally here, and it is a masterpiece. A semi-autobiographical tale that draws its Japanese title, How Do You Live?, from a novel by Genzaburō Yoshino that Miyazaki’s mother gave to him in his youth, The Boy and the Heron is a dark, dreamlike vision of life, death, and creation as seen through the eyes of our most singularly magical cinematic storyteller.

Strange New Worlds

It’s 1943, and war is raging. Eleven-year-old Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki) is still grieving the tragic death of his beloved mother in a hospital fire when his father, an air munitions factory owner named Shoichi (Takuya Kimura, who also voiced the titular wizard in Howl’s Moving Castle), announces that they’re evacuating Tokyo. The two of them move to the country estate of Mahito’s new stepmother, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who happens to be his mother’s younger sister—and she’s also pregnant with a new sibling for him. Needless to say, it’s a lot of change for one young boy to deal with, even one as seemingly stoic as Mahito.

One day, after fighting with other kids at his new school, Mahito hits himself in the head with a rock, enabling him to stay home and recuperate from his injury. But instead of staying in bed, Mahito follows a strange gray heron (Masaki Suda) deep into the woods surrounding the estate. The heron, who is actually a small shape-shifting man inside a heron’s body, tells Mahito that his mother is still alive; if Mahito enters the mysterious tower that his great-uncle—a man who supposedly went mad from “reading too many books”—built in the woods many years ago, he’ll be able to find her and save her. What child could resist such a challenge? Not Mahito, especially after he sees Natsuko venture inside; if he cannot save his birth mother from her fate, he can at least save his new stepmother.

What follows is a wild ride down the rabbit hole reminiscent of Chihiro’s adventures in the world of kami in Spirited Away. Inside the tower, Mahito finds a world that somewhat resembles his own, albeit through the lens of a dream, with that same twisted sense of logic. It also seems to exist outside of time; he encounters a fisherwoman named Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki) whose name and appearance indicate that she’s a younger version of one of the old maids working on Natsuko’s estate, as well as the absolutely adorable Warawara—pudgy, floating white creatures that are the spirits of lives yet to be born in Mahito’s world. He also meets Himi (singer-songwriter Aimyon), a young girl with the power to wield fire who may or may not be someone from Mahito’s own past. (It’s honestly pretty easy to guess who she is, though that doesn’t make her character’s relationship with Mahito any less powerful to watch unfold. Also, Himi is the character in The Boy and the Heron whose design—striped dress, crisp white pinafore, fiery hands—feels like it will inspire the most cosplay in the future.)

The Magic of Miyazaki

As Mahito and the heron venture deeper into the strange world, the plot of The Boy and the Heron grows increasingly difficult to unravel. The great-uncle reappears in the guise of the world’s creator and tries to convince Mahito to take his place. A kingdom of gigantic, man-eating parakeets seem intent on blindly consuming everything and everyone around them without thought of the consequences. (We all know what that’s a metaphor for…) The characters contemplate a world without malice, and whether or not that’s even possible; perhaps, through the actions of the younger generation, such a world could be created someday. Needless to say, if Miyazaki never makes another movie after The Boy and the Heron, this optimistic note of hope for the future would be a fitting coda to a career that has continuously focused on themes of compassion, loyalty, love, and pacifism—all necessary building blocks for creating such a world.

Still, even if you have a hard time keeping track of what’s going on in The Boy and the Heron, it’s impossible to not enjoy watching it all unfold. The animation is as colorful and imaginative as one expects from Studio Ghibli; from the craggy visages of the old maids bustling around the estate to the terrifying cottage where the parakeets are preparing for supper—very Hansel and Gretel—to the pelicans that soar through the night sky and attempt to swallow up the Warawara before they can be born in the other world, Miyazaki remains a master of melding the gorgeous and the grotesque to create images that remain enshrined in your mind for years to come. His extraordinary visuals do not exist to mask and distract from some lack of emotional depth, but to accentuate and articulate the intense, authentic emotions inherent in each of his stories—not to mention, the sense of childlike wonder that we all have at some point in our lives and would do well to hold onto as long as we can.

As a child, who didn’t dream of escaping the mundane world of reality and all of our troubles in it for a more fantastical world of magic and mayhem? Miyazaki’s most memorable films—Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and many others—allow us to live vicariously through his protagonists as they embark on such journeys; as they learn important lessons, so do we. The Boy and the Heron just happens to feature one of Miyazaki’s most relatable protagonists yet, a young boy who is complex and flawed and channels his emotions into stupid, self-destructive things. Even if you have not experienced childhood trauma on the level of Mahito’s, you’ll likely relate to his overwhelming sense of loneliness and sadness and his misguided attempts to submerge those feelings deep within himself instead of sharing them with those closest to him. Obsessed with the idea that he could not save his mother—an idea returned to again and again in nightmarish sequences of flight through fire and smoke—Mahito seizes the first opportunity presented to him to save someone else in her place, though we (and Miyazaki) know it will take more than that to finally heal those old wounds and begin anew again.

Conclusion

Miyazaki might be 82 years old and still unwilling to really retire, but contrary to what he might say, that in no way means he’s past his best; if anything, The Boy and the Heron deserves a place among his most monumental works.

The Boy and the Heron is screening as part of the Spotlight section at this year’s New York Film Festival.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.