Christa Päffgen, aka Nico, only ever sang on three songs by legendary New York rockers The Velvet Underground, but her career and life were defined by it. Her own music – six studio albums over 18 years – is largely unknown, as is the fact she spent the autumn of her life in Manchester, northern England, and died suddenly at the age of 49. Susanna Nicchiarelli’s vivid biopic focuses on the German model/actress/singer’s tumultuous last two years, delivering a portrait of a self-loathing, middle-aged woman haunted by her past, while fighting a long-standing addiction to heroin.

The film starts in 1986 as Nico (Trine Dyrholm) and her young band of “amateur junkies” (as she contemptuously calls them) tour Europe. She’s utterly world weary; sick of talking about being “Lou Reed’s femme fatale”, in emotional agony over her absent son, and answering in the affirmative when a journalist asks if it’s true she recently tried to commit suicide. The fact she keeps going at all is down in no small part to Richard – John Gordon Sinclair playing a very toned-down version of Nico’s real-life manager, Alan Wise – who clucks around the singer like a mother hen and clearly thinks the sun shines out of her. She doesn’t seem to notice, and certainly doesn’t reciprocate, his ardour.

World of troubles

Despite being part of one of the most critically adored albums of all time (1967’s The Velvet Underground and Nico) and a clear influence on the punk and new wave scenes of the ’70s and ’80s, the singer has become something of a joke over the years – reduced to little more than a blowjob-dispensing groupie in Oliver Stone’s The Doors (1991), mocked for her deep, heavily-accented singing voice and vilified over claims of racism. Nico, 1988 is an attempt by Nicchiarelli to reappraise and restore her reputation as an artist, but also as a woman and mother. To show us there was a deeply flawed but extremely talented and sympathetic human being buried beneath the mountain of mistakes she made and world of troubles she invited.

A pall of melancholy and regret hangs over the entire film. Before we meet 40-something Nico, we encounter her as a child in the German countryside, watching with her mother from a safe distance as Berlin is bombed into submission during the Second World War. “The sound of defeat” Nico later calls the noise of the aerial bombardment and you wonder if she believes the die was cast for her from that moment. This gloomy, doom mood never quite dissipates, even when Nico finally kicks her heroin habit and announces she intends to become “a very elegant old woman”. It turns out windows of hope and joy in her life are all too brief, the fact they come to a juddering halt so quickly mostly due to the singer’s endless appetite for self-destruction.

If Nico, 1988 is defined by anything, it’s the singer’s relationship with her son, Ari (Sandor Funtek), who was fathered by the actor Alain Delon (The Leopard). Given up by Nico when he was only a boy – “I was too young and too crazy to care for him,” she admits – Ari has his own demons and Nico needs Richard’s help to get him out of the mental institution where he resides in France. Nico’s regret at losing the boy is palpable and Dyrholm – who is impressive throughout – ensures you see every bit of the singer’s heartbreak each time she mentions his name, or he strays into her thoughts.

Suffused with pain

Nico’s solo work tended to be every bit as difficult and challenging as the singer herself, with road manager Laura (Karina Fernandez) even telling Richard at one point: “Her music is hideous”. Haunting, wintry, nihilistic, with that stentorian Germanic voice over the top, the songs on albums such as The Marble Index and Desertshore are certainly an acquired taste, but Nicchiarelli cannily selects some of the singer’s more accessible numbers to put front and centre, including These Days and My Heart Is Empty. There’s also a particularly heart-rending version of Nat King Cole’s Nature Boy (“There was a boy, a very strange, enchanted boy”), while Alphaville’s gently mocking Big In Japan is also used effectively, not least when Dyrholm (A Royal Affair) gives us her own haunting take over the closing credits.

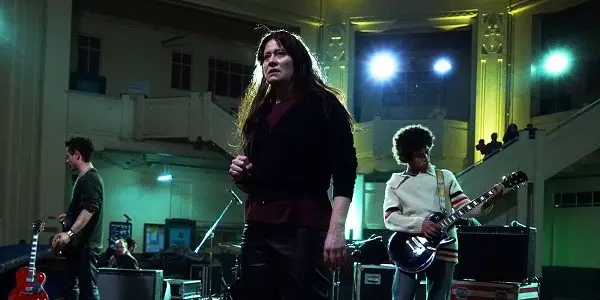

In fact, the Danish actress does a spectacular job of capturing Nico’s unique singing voice, unsettlingly intense gaze and, in one stand-out scene set in then-communist Prague, her magnetic stage presence too. Nico’s vocals were raw and suffused with pain and melancholy. She spoke to the damaged bit in all of us just as powerfully as Ian Curtis and Kurt Cobain ever did. Perhaps the only difference is that they died young and never had the opportunity to become parodies of themselves.

Stamp of authenticity

This is Italian writer/director Nicchiarelli’s third feature – after Cosmonaut (2009), La Scoperta Dell’alba (2012), and a raft of documentaries and shorts. She’s an economic, no-nonsense filmmaker who is clearly fascinated by all these characters, not just Nico. It isn’t quite an ensemble piece, but everyone gets their own space and you believe in them.

She also has a knack for creating visual moments, both poetic and memorable. We see Ari in a flashback as a young boy in a garden full of tortoises, then sipping surreptitiously from discarded glasses of alcohol at a party, and later in a vision Nico has of him as a ghostly adult in a graveyard. These are unsettling, off-kilter fragments that take the film into more obviously surreal territory. Nicchiarelli also cleverly incorporates Super 8 footage shot during the ’60s by the ‘godfather of American avant-garde cinema’ Jonas Mekas. They provide dizzy, fast-moving glimpses of Andy Warhol, the Velvets and New York, and give the entire enterprise a stamp of authenticity.

Scabrous and funny

The danger of biopics that concentrate upon only a brief period in the life of their subjects is that too much important stuff is left out. That’s unlikely to be a problem if you’re au fait with Nico and her work but could well be an issue if you’re encountering her for the first time. It also means Nicchiarelli gets to ignore or downplay certain aspects that may have shown her in an even less flattering light, such as accusations of racism and antisemitism (her friend Danny Fields called the singer “Nazi-esque”), and the allegation, in Susanne Ofteringer’s documentary Nico Icon (1995), that she got Ari hooked on heroin.

Nicchiarelli also presents us with a rather vanilla, cleaned-up version of some of the events described in former Nico band member James Young’s scabrous and funny book, Nico: Songs They Never Play On The Radio. Sometimes you feel the director is holding back too much on the bacchanalia and bad behaviour. It’s okay, we’re adults, we can handle it! While we’re picking nits, the film is also a little lopsided, with the 1986 chapter taking up a far larger chunk than ’87 or ’88, despite the latter giving the movie part of its title.

Nico, 1988: Final Thoughts

Nicchiarelli‘s film respectfully marks the 30th anniversary of the late singer’s death while attempting to restore a little of her legacy. Yes, Nico’s tawdry heroin addiction is omnipresent here, but the director successfully cuts through its pernicious influence to illuminate the complicated, infuriating and occasionally brilliant woman beneath. Dyrholm is convincing, frequently electrifying, as the doomed singer.

What is your favourite biopic of a rock or pop star – Walk The Line, Control, or something else? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below!

Nico, 1988 will be released in the US on August 1, 2018. For all international release dates, see here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.