Music in Film

Mason Manuel is a avid film reviewer and geeks out…

“Music and cinema fit together naturally. Because there’s a kind of intrinsic musicality to the way moving images work when they’re put together. It’s been said that cinema and music are very close as art forms, and I think that’s true.” – Martin Scorsese

The Godfather. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Lord of the Rings. So many great films made into legends with the accompaniment of game changing scores. Music has been paired with film since the silent movie era, from full orchestral compositions to a single vocalist. Generally, the composition is designed to emphasize what is happening on screen, but often it works both ways. The passing of a lightsaber may not seem as epic without John Williams’ mystical tones, but Klaus Badelt’s He’s a Pirate would not be nearly as lively and adventurous without a swashbuckling Johnny Depp pirating on screen. The companionship is organic, with both aspects of the film reacting to the other until (when done right), a beautiful cinematic experience is created.

Time for a short history lesson

The silent era was (obviously) named so because coordinating actors’ voices with what happened on screen had not been possible at the time. Music was added more to drown out the sounds of a rattling projector than it was to bring life to screen. In this time, most scores were not even composed to fit in with the picture. It was not until the production of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation that a composition was actually created to mesh with the film. Still, music was minimally used until the mid-1930’s, which gave birth to sound pictures. The film Singin’ in the Rain visualizes this movement and is definitely worth a watch if you haven’t seen it already.

Music began to be used as a main trait in the story instead of just background noise. Max Steiner wrote the first completely original score for a movie, the 1933 groundbreaking King Kong, which had an incredible result. The horrific score had an emotional effect on the audience – the shrill and dramatic instrumentation had viewers curl in fear, anticipating the next destructive appearance of the monstrous ape. Seeing the physical effect music had on audiences made film directors rethink the potential of tailored scores, and began a very aggressive movement into this newly discovered aspect of the industry.

Many notable directors began to foster relationships with their favorite composers to create films that served the score as well as vice versa. The earliest, most notable of these relationships was between the esteemed Sergio Leone and the equally regarded Ennio Morricone. Morricone became famous for his use of non-instrumental objects to create a score. Bullwhips, whistles, gunshots and more all became main tools to be used in the composition. He was once shown in an interview demonstrating his composition process by pressing different keys on a typewriter in rhythm. It was a stunning success and both director and composer were and are considered geniuses of their time.

Of course, it does not take an original score to create a fantastic soundtrack. Directors began adding already existing popular music to emphasize film. Quentin Tarantino is particularly famous for this. Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill are especially popular for their sometimes bizarre accompaniments, whether it be Bustin’ Surfboards playing on the radio as two gangsters discuss the fidelity issues of a foot massage or Woo Hoo being paired with Uma Thurman gutting dozens of members of the Crazy 88 gang. Even popular artists began to be recruited to create scores for film as opposed to recording albums, such as Sir Elton John with The Lion King. As film continued to evolve, so too did the art of their accompaniment.

Different film scoring strategies

There are a variety of techniques used to score, but film music is mainly categorized into either diegetic or non-diegetic labels. Diegetic music is defined as audio which comes from a source within the happening of the film. Back to the aforementioned Pulp Fiction, the opening credits with the switching of songs on the radio is an example of diegetic scoring. Music coming from nowhere, such as an orchestral arrangement being played in the background, is considered non-diegetic. Music is not limited to these two techniques however; there is a middle ground.

The recent Academy Award winner for Best Picture, Birdman, has a soundtrack that mostly consists of percussion with only slight additions from other instruments. While this music normally comes from nowhere, the camera occasionally stops to notice a drummer beating along right in time with the score being played. He is depicted in a number of scenes, being spotted as a bucket drummer in one scene and a dressed up concert percussionist in another. Two things remain consistent: the drummer himself and the score. In part due to the masterful direction of Alejandro González Iñárritu and the scoring of Antonio Sanchez, the diegetic and non-diegetic sources mesh together perfectly. This coupling demonstrates the apex relationship between composer and director, and between film and score. It is an organic, symbiotic pairing that has both sides contribute to the other to make something incredible.

Composers that hit the right note

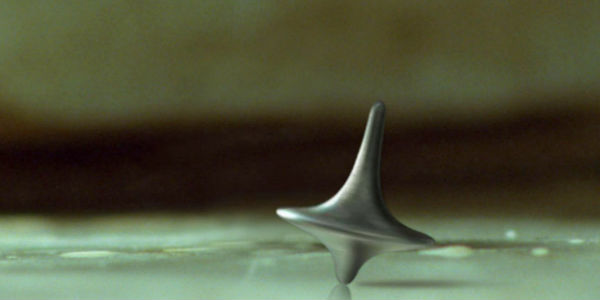

There are far too many impressive film scores and composers to mention in one article, so here are some suggestions that could be used as a starting point. I cannot write an article about music in film without mentioning the incomparable Hanz Zimmer. Zimmer has made such a name for himself in scoring that he has created his own company where he collaborates with a number of composers to belt out composition after composition. Arguably most notable are his pairings with director Christopher Nolan. Both the Dark Knight Trilogy and Inception have amazing scores that envelop viewers into the insane events that happen on Nolan’s screen.

Lalo Schifrin is a four-time Grammy Award winner most famous for his composition of the Mission:Impossible theme. The soundtrack has been reiterated time and time again but never loses its original sense of adventure. Also worth note is his work on the Dirty Harry films and Enter the Dragon. In spite of his fame with these rather dramatic scores, he is better known for his work with jazz.

John Williams most likely wrote the soundtrack to your childhood. His frequent collaboration with Steven Spielberg has resulted in the unforgettable tracks to classics such as E.T., Jurassic Park, and Jaws. Williams is famous for his use of Neoromanticism and leitmotifs. Leitmotifs are common themes found throughout a score, such as the “dun, dun, dun, dun” from Jaws. Leitmotifs are useful in that they symbolize that the main star of the movie is making waves (wink wink) in the story and probably will be doing something dramatic in a moment if they are not already. Williams makes use of this technique with grace, never overusing it, but having included enough to ensure that the viewer always stays on the edge of their seat waiting for the next iteration.

If classic is more your taste, look no further than Bernard Herrmann. This composer worked numerous times with Alfred Hitchc*ck and made his name by composing the soundtrack to Psycho using nothing but strings. This soundtrack was groundbreaking as no one had realized how much power a single instrument had until they saw it personified on Hitchc*ck’s silver screen. Herrmann also worked with Martin Scorsese for his hit thriller Taxi Driver, using foreboding tones and drawn out notes to instill an aura of fear around the violent main character. His work in personification through music was astounding, and his influence can still be seen today.

To cap off our list here, we present to you the oh-my-god-he-won-so-many-awards-he-nearly-drowned-in-them John Barry. Most popular for his composition of the original James Bond theme along with scoring 11 of the series’ iterations, Barry became the proud owner of 4 Oscars, 2 Oscar nominations, 4 Grammys, 2 BAFTA awards, a Golden Globe, and strangely the Golden Raspberry for Worst Musical Score (concerning 1982’s The Legend of the Lone Ranger). Much like Ennio Morricone, Barry began his musical career studying the trumpet. As he became more experienced he graduated into composing and created some of the most memorable scores to date for films like Dances with Wolves and The Lion in Winter. This composer was known for a heavy accent on bass and strings, but he also became one of the first to employ a synthesiser to his scores. This brave innovation resulted in the synth being used more regularly until it became a regular addition into scoring, making Barry something of a pioneer for his time.

(Note: There are many more composers of note that are worth becoming familiar with whom have not been listed. If you find yourself yearning for more composers to study try some of these: Max Steiner, Howard Shore, Nino Rota, Leonard Bernstein, Klaus Badelt, Thomas Newman, and Michael Giacchino.)

Where Do We Go From Here?

Music is nothing if not an evolving process, and since its conception, the art has only gotten more imaginative. Composers today use instruments that better illustrate the happenings on screen, and find mind-bending ways to combine diegetic and nondiegetic music in seamless ways. For example, in recent movie history we have had a number of blockbusters set in space, most notably Gravity and Interstellar. Interstellar’s score was criticised heavily for its gratuitous organ, but reportedly composer Hanz Zimmer had his reasons for it. See, pipe organs run primarily on the usage and manipulation of compressed air. The louder the organ is, the greater the need is for air. Apparently, Zimmer saw this instrumental trait as a clever way to illustrate the character’s desperate need for survival while exploring the dark, merciless vacuum that is space.

You will notice in moments of high distress, being in space or in air the organ bellows at its mightiest volumes, so much so that it nearly drowns out the actors to where you cannot hear what they are saying. Again this was criticised, as viewers were afraid that they were missing important plot details in the spoken dialogue, but think about it – when you feel distressed or are in a moment of physical anguish are you listening to what other people are saying, or have you retreated more into yourself to assess the damage? Director Christopher Nolan said in an interview that the sometimes overbearing volume of the music was done on purpose, so it would be fair to assume that the audience was meant to feel overwhelmed by the music more than the dialogue being spoken on screen. For better or worse, the organ did its job in harnessing the attention of viewers during moments in the film, leaving the screen feel nearly breathless when the instrument was absent. Whether it was done on purpose or not, the organ illustrated the need for air well and goes to show that instruments being paired with the physical ongoings happening on screen can be an engrossing experience for audiences.

Scores have become much less complex in these past few years compared to films that came out back in the late 1900’s. Rather than a complex, near-Mozart level of composition, we are given simple note progressions. The reason for this change? As the king from Amadeus stated: “Their are in fact, only so many notes the ear can hear in the course of an evening.” And he’s right. A complex score might be great in a concert hall where the music is meant to be the sole focus of attention, but in film it can be rather pretentious. So how is a limit on musical range bolstered to create an impressive score? Composers today create much more textured scores, using a great variety of instrumental power to birth physical reactions in the audience.

More and more put greater emphasis on diegetic music, starting perhaps with a simple guitarist on a bench in a park, and then contributing to said guitarist with a background score. These additions add further depth to scores and connect greater with viewers without them even realizing it.

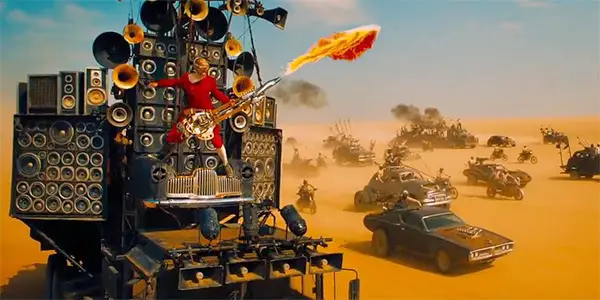

Take Mad Max: Fury Road for example. George Miller’s baby takes place in the middle of a barren wasteland which one would assume hasn’t heard an instrument in a while. But what’s this: a giant guitar rig, complete with a dozen strapped amps and a drum line fastened to its back. The moments in the film where this rig and the score mesh are simply breathtaking. What’s amazing is that this dramatic movement is so effective that it makes you hold your breath in excitement without even noticing; that is how powerful the technique is. And it’s only getting better as time moves on. With each new year, new and bolder techniques are introduced and experimented with, creating fresh new experiences for moviegoers. The only question now is, what comes next?

Film and music are beautiful forms of art, but together they rise to a whole other plane of imagination. When done right and paired by experts in their field of cinema, the sky’s the limit.

What are some of your favorite film scores? Let us know in the comments!

(top image: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) – source: United Artists)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Mason Manuel is a avid film reviewer and geeks out at every Star Wars convention no matter how many Jar Jars there are. When he's not busy on film inquiry, he writes and plays games on his own blog. Follow him on twitter @reeldudereviews.