How A Film’s Music Manipulates Our Emotions

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film &…

Guardians of the Galaxy broke records this year when its soundtrack reached number one, making it the first soundtrack in history to reach number one with no new songs on the album. This got me thinking about great soundtracks and the use of popular music versus composition. There’s a time and a place for both, and sometimes a time for none. Several filmmakers have mastered pinpointing those moments.

Merits of Soundtrack

Juxtaposing a scene or scenes in a film with popular music actively engages the audience, especially if you’re trying to target a specific group. It can also help enforce character traits. With Guardians of the Galaxy, the music served as Starlord’s connection to both his mother and planet Earth. Another recent film, What If, employed a heavily folk-influenced, but modern soundtrack, which worked really well for the indie, slightly-hipster vibe they were going for. Since the viewer may already have an established emotional link with the music being used, a filmmaker can use this to his or her advantage (this can obviously work against a filmmaker if the emotional response is a negative one and that isn’t the intention).

From a financial point of view, soundtracks outsell scores and bands are always eager to get one of their songs on a big film. One of the most popular songs of this year was “I See Fire” by Ed Sheeran, for The Hobbit: Desolation of Smaug. Featuring in a film also helps independent bands gain larger fanbases. The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, while featuring bands like Coldplay and artists like Christina Aguilera, also had tracks from The Lumineers and Of Monsters and Men, who, though popular, are marginally less known.

Merits of Score

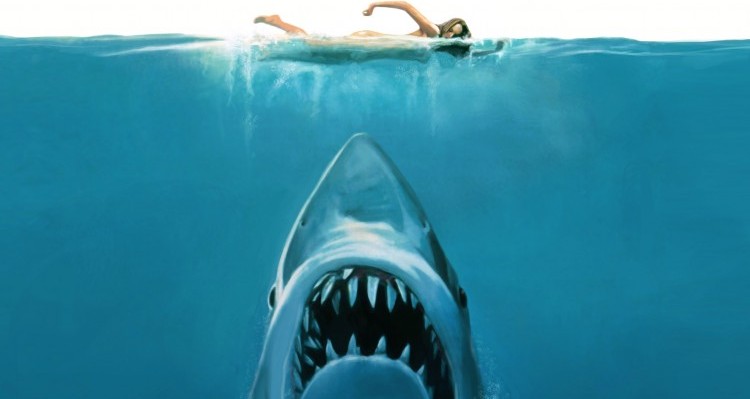

Despite the financial incentives of a soundtrack, oftentimes composing an original score can provide a film with a unique soundscape that a viewer will then forever link with the film. Just think of the theme from Jaws, or the shower scene in Psycho. In no situation can you hear those pieces of music and not associate them with their films, even if only indirectly.

Scores allows the filmmaker to have complete control over the music, even down to the instruments being used and the level at which each instrument plays. Scores also tend to be more useful than popular music when dealing with films based in history, particular pre-album history. It helps keep disbelief suspended and generally comes across as less intrusive to the audience.

Breaking the Rules

There’s no point in having rules without being able to break them! Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t – there are many ways to go about it. One option involves removing music from your film, sometimes almost entirely. The film which most readily springs to mind for me is No Country For Old Men. The Coen Brothers managed to create enough atmosphere and emotion that adding score or soundtrack would’ve been superfluous. There are two or three brief moments in the film where a bit of score is used but for 122 minutes of run time, only 16 of those minutes contain any non-diegetic music.

Another twist films sometimes employ is to blur the lines between diegetic and non-diegetic music (this does not include musicals, which are a breed unto themselves). My favorite example of this is A Knight’s Tale (there are others but I am in the “A Knight’s Tale is awesome” camp and I’m recruiting). There’s the classic bit with “We Will Rock You” by Queen being sung by the lowly peasants watching the joust, but then there’s the absolute star of a scene where “The Golden Years” makes a seamless appearance in the ballroom dance sequence. Director Brian Helgeland used these bits of pop culture to engage the target audience of the film (teenagers) AND their parents (older people). It worked on a couple levels because kids enjoy hearing pop music in films and their parents recognise the classics and the cheeky way they’re utilized.

Music is one of many powerful art forms. When combined with film it elicits some of the most profound emotional responses we experience as a collective. This is most effective when the creative team involved – be it directors, composers, producers, editors, et cetera – use the two arts constructively and with a sense of balance. When done right, the effect is beneficial for both the viewer and the film.

What are some of your favorite soundtracks and scores? Which ones miss the mark? Tell me in the comments!

(top imageimage source: Jaws – Universal Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film & tv production lecturer at the University of Bradford and is also completing a PhD about Stan Brakhage at the University of East Anglia. In the remaining "spare time", Jax organises the Drunken Film Fest, binges bad TV, and dreams of getting “Bake Off good” with their baking.